Professor Hajime Nishitani, from the Office of Global Initiative at Hiroshima University in Japan, outlines English education reform-based on EBPM (Evidence-Based Policy Making), including comment on English and Japanese Students in general

The population of 18-year-olds in Japan has been dropping dramatically since its peak of 2.05 million in 1992, to approximately 1.18 million in 2018. It is estimated that this number will plateau at approximately 1.1 million for the next two decades.

Under such circumstances, for Japan to maintain and enhance its competitiveness in education, research and industry, students must be educated with the relevant knowledge, skills and competencies. In particular, given the larger and ongoing processes of globalisation, the ability to communicate effectively has become integral to Japan’s economic and social stability and advancement, both nationally and internationally. Most importantly, because English has become the de facto lingua franca, Japanese students must dramatically increase their competence in English if Japan is to remain competitive, both nationally and internationally.

The Japanese Government once suggested that there has been a steady increase in “global human resources” who demonstrate “communication skills for business conversation and paperwork.” However, Japanese people still lack “linguistic skills for bilateral negotiations“ and “linguistic skills for multilateral negotiations.”

For example, note that in one cross-country comparison (2010 TOEFL), Japan scored very low, at 135th out of 163 countries and 27th out of 30 countries in the Asia region.

As such, the Japanese Government emphasised the following global human resource issues:

- Issues related to elementary and secondary education, such as promoting overseas studies during senior high school.

- Issues related to university education, such as improving university entrance exams.

- Issues related to economic society, such as improving recruiting activities.

The Japanese Government also proposed to introduce various educational reforms, including the introduction of English language education in elementary schools and the development of a university entrance exam that tests the four language skills.

In the 2018 TOEFL scores ranked by country, Japan again scored very low, 145th out of 170 countries and 27th out of 30 countries in the Asia region (i.e., Asian countries, such as Cambodia, Vietnam and Taiwan, substantively increased such competencies). In short, Japan has remained stagnant while other regional and international countries have increased English competencies.

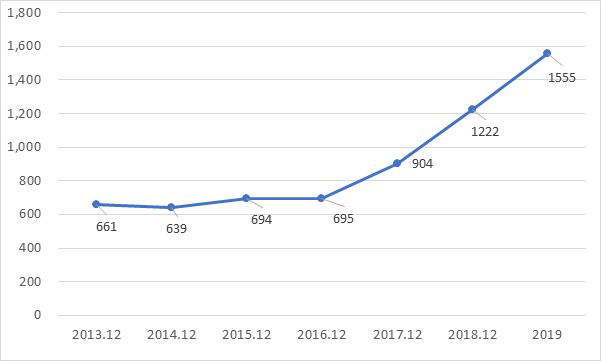

In contrast to these multi-year trends in Japan, Hiroshima University has demonstrated substantially increased in English language acquisition. Utilising the framework of TGP (Top Global University Project: Type A), which is financed by MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan), Hiroshima University successfully increased CEFR B2 level student numbers through an integrated and targeted approach. By way of historical context, in 2014, the TGU Project at HU sought to implement, based upon EBPM (Evidence-Based Policy Making); prior to 2016, the number of CEFR B2 level students had not changed almost at all for more than a decade.

As Figure 1 illustrates, by using evidence-based education reforms and a psychology-based competency test, called the BEVI (the Beliefs, Events and Values Inventory) (Shealy, 2016), Hiroshima University increased the CEFR B2 level students number by 223% in three years.

EBPM at Hiroshima University

Hiroshima University has been working with internationally renowned experts on the assessment of international education and explored mediators and moderators of English language acquisition. By carrying out quantitative and qualitative research into English language competency across the university undergraduate faculties and schools (an estimated 10,000 students), we have come to understand: 1) why some students score better than others; 2) which schools are most successful and; 3) where global education programmes are failing students. All of this information is used to improve the chances of student success in the future.

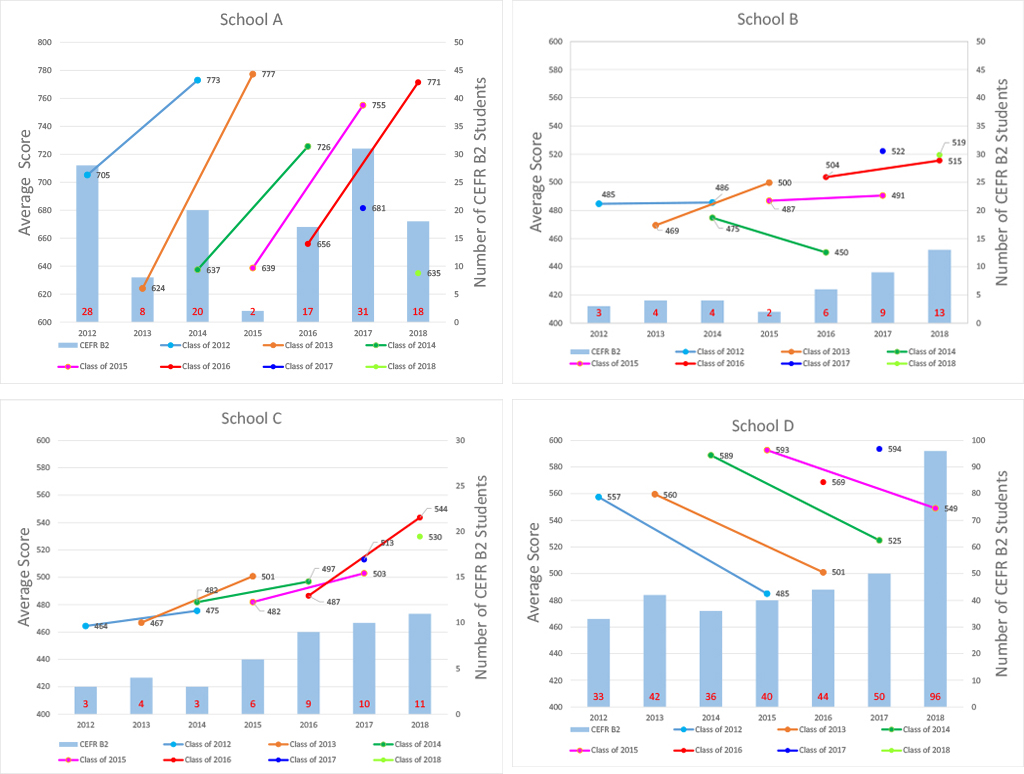

For example, it has become clear that different faculties, schools and departments are characterised by distinctive score profiles, results which are generally replicated from year to year. Figure 2 illustrates these patterns. That is where the BEVI helps to illuminate the underlying mediators and moderators (i.e., the factors that influence or affect English language acquisition).

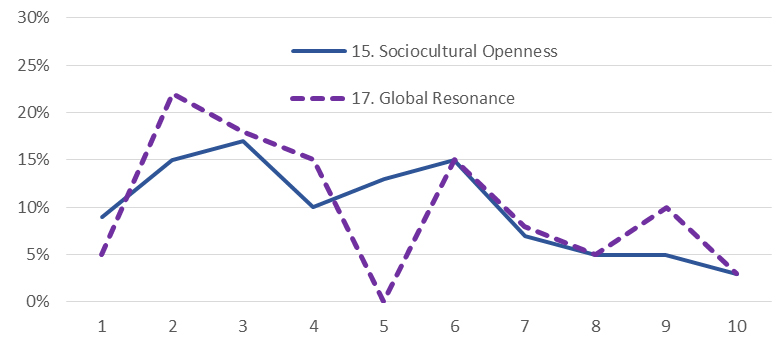

A grounded theory and mixed methods assessment measure, the BEVI is a powerful analytical tool that can show the capacity of an individual student toward “sociocultural openness” and “global resonance” among other aspects of how individuals experience self, others and the larger world. Recently, HU tested nearly all 2,400 freshmen students on the BEVI, obtaining an 80% response rate.

Subsequent analyses identified: 1) relationships among variables measuring psychological characteristics, academic faculty emphasis, students career paths and other variables and; 2) how such interacting and data-based factors are predictive of the relative degree of English language proficiency. Amongst the other findings, it has become clear that students within specific faculties or schools evidence a wide and measurable range of motivations, capacities and competencies. This repeated observation suggests the need for a more individualised approach to English acquisition.

Consider Figure 3, for example. Here we see the extraordinary range of student capacities and inclinations toward “sociocultural openness” and “global resonance,” two BEVI scales which measure the degree to which individuals are open to, interested in and engaged with cultures, values and practices that are different from their own. By way of interpretation, note that the majority of students in this school are at the lower end of each of these scales (below the 40th percentile), but a significant minority of students in this same school are at the upper end of these same scales (above the 60th percentile).

The Individual Target Score (ITS)

To address these profound differences within the student body – a process that we see across faculties and programmes – Hiroshima University has adopted an Individual Target Score (ITS). Now, the University sets an ITS for each student every six months, using in part entrance examination scores. Each ITS also is converted into a graphical representation, with explanations, for each student. In this way, each student can compare their current score with their target score regularly. Juxtaposed with these scoring system, HU also integrates university-wide English intensive programmes and study abroad programmes.

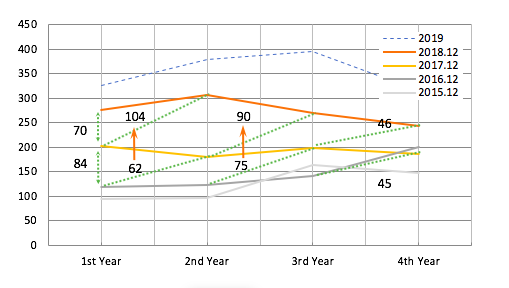

As Figure 4 illustrates, the number of first-year students who reach CEFR B2 level is increasing when English language education is concentrated. More specifically, the number of students with CEFR B2 level continued to increase as evident by comparisons between first, second and third-year students. In 2017, for example, when this new approach began to be implemented, major changes began to occur.

Note (via the yellow line), that the number of students reaching CEFER B2 in the first year increased by 84. When those same students entered their second year, the number of students with CEFR B2 level increased by 104. Moreover, not only are student numbers increasing, but the difference between years is also widening. For example, in 2018, the number of students reaching CEFR B2 increased from 62 to 104 in the second year and 75 to 90 in the third-year compared to 2017.

In short, we attribute the marked changes we are seeing to the comprehensive and integrated usage of measurement, combined with individualised tracking of progress and more targeted and intensive programming designed to enhance English language acquisition. As we continue to refine our approach and understand better the interactions among the factors that are associated with such learning, we wish to expand this model and method not only internally at Hiroshima University, but to other institutions across Japan. Ultimately, we expect that this data-based approach may help Japan graduate more English proficient and internationally-minded students who have the competencies necessary to engage the wider world while maintaining and enhancing our economic standing at home and abroad.

*Please note: This is a commercial profile