According to IIASA research, personal experiences of extreme weather have a lot to do with political voting patterns – particularly for green parties

Researchers from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) have analysed the effect of personal experiences with climate extremes, on environmental concerns and voting patterns. The team explored to what extent changes in concerns translated to actual support for climate action, in the form of green voting.

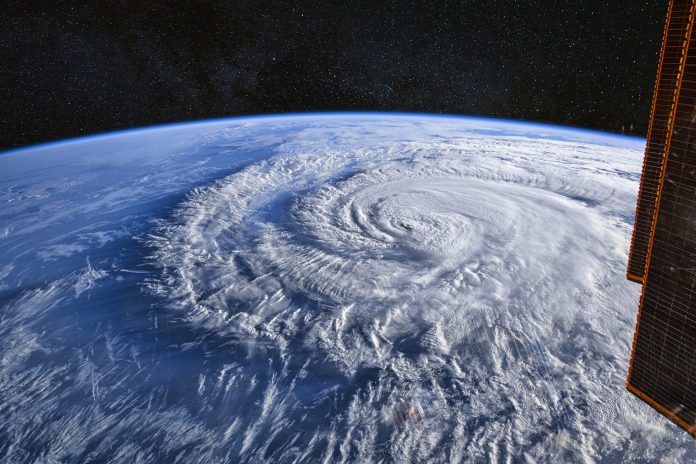

In previous decades, European nations remained unharmed by climate change – leaving many European citizens unable to sympathise with the climate cause. However, in the last several years, there has been an increase in climate disruption and extreme weather around the world – particularly in Europe.

In 2021, the number of wildfires more than doubled from the annual average of the past 10 years. Many European countries were hit with extreme flooding. Climate mitigation and action is required now more than ever to prevent irreversible damage to the planet and the climate events of the last few years only illustrate this point further.

Experiencing climate extremes

For this study the IIASA team used time-series Eurobarometer data (42 survey waves, 2002–2019) and European Parliament election data (6 elections, 1994–2019) to analyse changes in concerns and voting at the subnational level across 34 and 28 European countries, respectively. The team then combined this data with climatological data to discover that the rise in climate concern and voting for green parties can be partly attributed to more frequent and intense experiences with climate extremes.

This increase was particularly higher in Northern and Western Europe and weaker in Eastern and Southern Europe. Although trends in green voting are erratic over time, there is a clear North-West and East-South divide with higher shares of Green voters in the North-West.

The analysis of the extensive data collected by the team shows that the rise in climate concerns and voting for Green parties can partly be ascribed to the more frequent and intense experiences with climate extremes. The impacts of climate extremes were, however, not uniform but differ from region to region.

“Populations in these regions may have already adapted to the warmer, drier baseline conditions, for instance, with respect to housing and agriculture, or they may be more used to temperature-related extremes, making the extreme events become less noticeable,” noted Jonas Peisker, a researcher jointly associated with the IIASA Equity and Justice Research Group and the Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academic of Sciences.

What else effects green voting?

Factors such as socioeconomic, cultural and political conditions in a region can also play a pivotal role in explaining the noted difference in voted across the regions.

The study found that economic conditions moderate the climate impacts on concerns and voting, suggesting that while climate change experiences increase public support for climate action, it only does so under favourable economic conditions.

According to Raya Muttarak, former IIASA Population and Just Societies Program director: “regions with a more highly educated and younger population tended to respond more strongly to climate extremes by adapting their environmental concerns and changing their voting behaviour.”

The potential implication of this research

The EU has placed itself at the forefront of environmental protection and climate mitigation, however economic challenges and political disruptions might hinder their ability to fulfil its role of policy innovation.

Roman Hoffmann, a researcher in the Migration and Sustainable Development Research Group of the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program, said: “Our findings highlight the importance of increasing the salience of climate impacts in an inclusive way. There is a need to address the substantial geographic differences in public concerns and political support for climate action across regions in Europe.

“Obviously, exposure to climate change impacts is not the ideal way to promote public concern and action, but climate communication and education can help fill the experience gap. This could help to reduce people’s psychological distance to the effects of climate change and to encourage mitigation behaviours.”