The first ever woman cured from HIV underwent a dual stem-cell transplant, which seems to have made her genetically resistant to HIV and put her cancer into remission

As a result of the mRNA push made by COVID vaccines, researchers are now trialling mRNA HIV vaccines. In the UK, initial results are expected for a HIV vaccine that has been delayed for a couple of years, due to the lab switching priorities to help design the infamous AstraZeneca vaccine.

It seems that after decades of inevitable death transforming into accessible, condition management, cures for HIV are appearing on the near horizon.

First ever woman known to be ‘cured’ from HIV

On Thursday (24 March), The International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trial Network (IMPAACT) reported the first ever woman cured from HIV. In the past, there have been two anonymous individuals who have achieved HIV remission, making this case the third in known history. Sadly, the ‘Berlin patient’ died of leukaemia in 2020, after a successful case of HIV remission.

The woman, of mixed-race ancestry from New York in the US, developed high-risk acute myeloid leukemia, four years after a HIV diagnosis. She stopped antiretroviral therapy (ART) at 37 months post-transplant. After this point, she has had no detected HIV for a total of 14 months.

Dr Larry Corey, professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and not involved in this study, said: “With intersecting pandemics, we must re-evaluate our approach in responding to HIV and COVID-19 through two major components: global immunization and enhanced services to people living with and at risk for exposure to HIV.”

How does the dual stem-cell transplant work against HIV?

A dual stem-cell transplant is only done when the patient also has another condition.

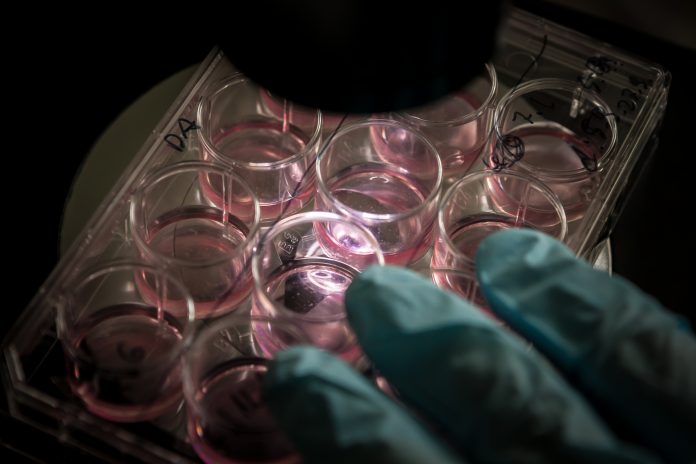

The dual stem cell (or haplo-cord) transplant is a new transplant strategy that involves the transfusion of stem cells from an umbilical cord of neonates, complemented with stem cells from the bone marrow of an adult donor.

In the case of the ‘New York patient’, that other illness was an acute myelogenous leukemia. She had to undergo a transplantation with cord blood stem cells with a CCR5 genetic mutation for treatment of cancer, hematopoietic disease, or other underlying disease.

This genetic mutation results in T cells without CCR5 co-receptors.

As HIV needs to use these co-receptors to infect T cells, the logic of the study is that chemotherapy given to people with cancers or other illness, followed by a transplant using stem cells that carry this CCR5 mutation, can stop HIV.

Essentially, reproducing the CCR5 mutation can stop the body from being infected by HIV, making it genetically resistant.

Can this method work for millions of others living with HIV?

Sadly, no.

The CCR5 mutation, which gives such great results against HIV, is extremely rare. It is only found in 1% of the general population, which means that it would be difficult to extract and then give to others in stem cell transplants.

Even if the CCR5 mutation was more widely available in stem cell donors, the actual procedure is too risky to replicate across millions of people – unless they desperately need it.

The scientists describe the double stem-cell transplant as an “invasive, complex and risky medical procedure” which appears to be reserved and possible only for those suffering a duo of diseases.

However, the lack of scalability does not diminish the hopeful outcome of this case.

“Despite of feasibility challenges, this new HIV remission case is very exciting news and will continue to energize the HIV cure research agenda, reminding us of its potential to beat HIV,” said Dr Meg Doherty, Director of WHO’s Global HIV, Hepatitis and STI Programmes.