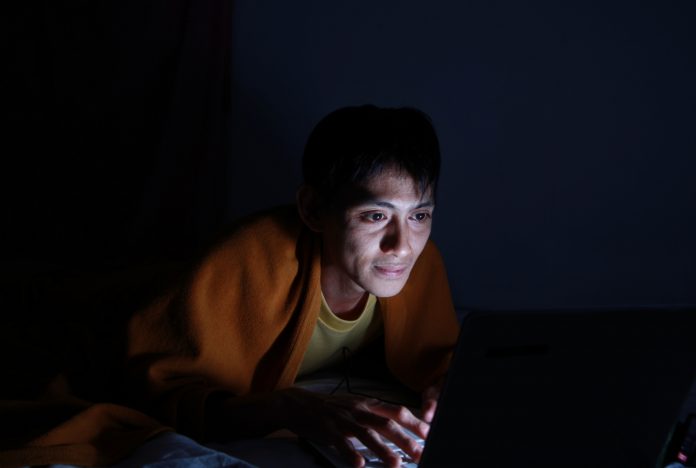

A significant increase in online searches for “insomnia” signalled to researchers that the first COVID lockdown was hard-hitting on mental health in the US

With job losses, rising healthcare costs, a fiercely divided Presidential election and the wavering uncertainty of a country that has not seen a virus epidemic on this scale, it is no wonder that the US experienced a collective strain.

Insomnia involves difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, or regularly waking up earlier than desired, despite allowing enough time in bed for sleep. Daytime symptoms associated with insomnia include fatigue or sleepiness; feeling dissatisfied with sleep; having trouble concentrating; feeling depressed, anxious or irritable; and having low motivation or energy.

2.77 million Google searches for insomnia

Results show there were 2.77 million Google searches for insomnia in the US for the first five months of 2020, aka the first COVID lockdown. This was an increase of 58% compared with the same period from the previous three years.

While searches for insomnia trended downward from January through March 2020, consistent with prior years, they surged upward in April and May 2020. This increase was understandably associated with the cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths in the spring.

The researchers analysed Google search data in the US and worldwide between January 1, 2004, and May 31, 2020 – the first COVID lockdown across the country. Data for the number of daily deaths from COVID-19 were downloaded from the freely available COVID-19 Data Repository maintained by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. Consistent with prior years, searches for insomnia in 2020 occurred most frequently during typical sleeping hours between midnight and 5 am, peaking around 3 am.

Implications for the US population

“I think it’s safe to say, based on our findings as well as those from survey studies showing an increased level of insomnia symptoms in certain populations, that a lot of people were having trouble sleeping during the first months of the pandemic,” said lead author Kirsi-Marja Zitting, who has a doctorate in physiology and neurobiology and is an instructor in medicine and associate neuroscientist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“While acute insomnia, typically triggered by stress or a traumatic event, will often go away on its own, I am worried that the longer this pandemic drags on, the greater the number of people who go on to develop chronic insomnia,” she said.

“And unlike acute insomnia, chronic insomnia can be difficult to treat.”

New guidelines form the American Academy of Sleep Medicine suggest that multi-component cognitive behavioural therapy is good for insomnia.