Islam Elkonaissi and Zahra Laftah from the UKCPA explore the British model of supporting excellence in clinical pharmacy practice

In the UK, evidence that pharmacists can provide better clinical outcomes and more efficient, consistent and sustainable services for patients, is increasing. In this article, key themes are discussed to showcase the importance of empowering pharmacists and fostering leadership in clinical pharmacy practice.

Context

The vision in the National Health Service (NHS) 5-year forward view (FYFV) (1) is for a sustainable NHS that continues to be tax-funded, free at the point of use and that is fully equipped to meet the evolving needs of its patients, now and in the future.

To deliver this vision, pharmacists are supporting efficiencies in the NHS and improving patient care by undertaking person-centred medicine reviews in a range of different care settings and as part of care pathways and multidisciplinary teams.

Medicines optimisation

Within the context of an NHS struggling to cope with an ageing population, prolonged life expectancy, large numbers of patients managing comorbidities and polypharmacy, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published a medicines optimisation guideline (2).

Key recommendations from NICE include efficient medicine-related communication across different settings of care, medicines reconciliation in addition to medication reviews. Pharmacists across the country have been leading on projects within the remit of these recommendations. This includes antimicrobial stewardship, diabetes referral tools as well as polypharmacy stop-start tools.

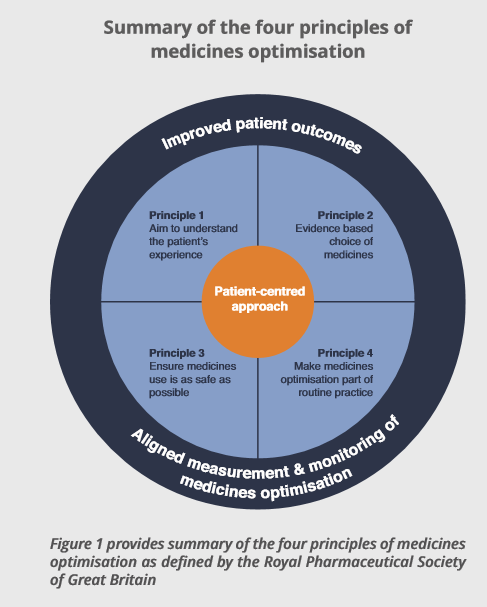

The four guiding principles (3) (figure 1) outlined by the pharmacy professional body, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPS) in 2013, describe medicines optimisation in practice and the outcomes it is intended to impact. These principles can be used by pharmacists as well as other healthcare professionals and this simply shows the level of influence by pharmacists through their professional body.

Medicines optimisation and cost efficiencies

Lord Carter’s efficiency review (4), which shed light on significant variations across NHS pharmacy services, was fundamental in paving the way for pharmacists to lead in new models of care in a financially sustainable manner. The Carter review highlighted that unwarranted variation in the use and management of medicines cost the NHS at least £0.8 billion, that could be reinvested.

Amongst other recommendations, Lord Carter recommended a Hospital Pharmacy Transformation Programme to ensure hospital pharmacies achieve their benchmarks such as increasing pharmacist prescribers, e-prescribing and administration, accurate cost coding of medicines and consolidating stockholding. The main objective of these activities is to ensure pharmacists and pharmacy technicians spend more time on patient-facing medicines optimisation activities.

The Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme (5) aids this vision by incentivising NHS organisations which achieve specific targets. Of particular relevance to pharmacists is the medicines optimisation CQUIN scheme. The goal of this scheme is to optimise the use of high-cost drugs, tackle variation and reduce waste.

The scheme highlights pathways to achieve this through:

- Adoption of biosimilars and generic switches.

- Improved drug data quality.

- Utilising most cost-efficient dispensing channels.

- Compliance with policies/guidelines to reduce variation and waste.

The future of what is known as Carter is envisaged through the “Top ten medicines” list identifying further productivity opportunities, as recommended by Lord Carter, opening up more roles for pharmacists. The list itself was developed in collaboration with a small group of Chief Pharmacists working in NHS organisations, with the aid of a tool known as “Define”. Savings targets for individual trusts are based on a baseline period and represent either a simple reduction in spend or on the uptake of a less costly alternative medicine. The following example demonstrates the huge role played by pharmacists in developing and delivering cost-saving efficiencies.

Learning from the Cancer Vanguard (6) in the UK

At the core of the FYFV strategy is the development of new models of care or the vanguards. It recognises that there are universal levels of care provision that require a degree of conformity. It has, therefore, proposed many new care models that are being explored and implemented via the vanguards.

The Cancer Vanguard (6) through a collaboration led by The Christie, The Royal Marsden, and University College London Hospitals, has provided a platform for a pharmacy to develop new models of cancer care that are replicable and transformational, which would ultimately act as blueprints for the NHS nationally. For example, a process timeline for adoption of biosimilars has been developed with accompanying guidance, resources and template documents to enhance biosimilar uptake within the NHS.

The replicability of both the process and the new models developed means that the national impact is substantial. With the support of pharmaceutical industry, other examples include adverse event monitoring of patients receiving immunotherapy, developing models of care for home delivery of chemotherapy, taking delivery of Denosumab out of hospital settings and the use of patient apps in metastatic colorectal pathways of care. Future opportunities are increasingly focused on prevention and early diagnosis with hospital- community pharmacy collaborations.

The Cancer Vanguard has therefore provided an example of collaborative and systems leadership in terms of how quickly results are being produced as well as its replicability. Openings for further joint work with industry and involvement in early diagnosis are key learning outcomes.

Initiatives towards resilient and competent pharmacy workforce:

To deliver leadership in practice, there is a certain need for workforce resilience and competence which are necessary to improve parity amongst different sectors of care. The following explores two examples of such efforts.

National training programmes

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society alongside the United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association (UKCPA) and other affiliated partners are in the final stages of developing National Training Programmes for pharmacists for all levels and sectors. This will support pharmacists, addressing pharmacy clinical training needs up to consultant level. It consists of components to suit each pharmacist’s scope and level of practice.

Each component of the programmes will be mapped to professional curricula and the Advanced Pharmacy Framework of the RPS6. Featuring an assessment within each module, pharmacists would be able to receive a certificate of completion to demonstrate evidence of their training to employers, commissioners, patients, the General Pharmaceutical Council and the Faculty Scheme (6) by the RPS.

Pharmacy fellowship schemes

Established in 2015, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer Fellowship schemes provide pharmacists at their early career with a unique opportunity to spend a year working with senior pharmacy leaders in national healthcare organisations. It enables fellows to lead on key projects which contribute to national healthcare priorities around patient safety, medicines optimisation, transfer of care, digitalisation and pharmacy workforce training. Host organisations for this scheme include, amongst others, Care Quality Commission (CQC), NICE, NHS England, Public Health England, NHS Digital and the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE).

Take-home message

This article summarises a few examples that demonstrate a central role for pharmacists in new models of healthcare in the UK. Empowering pharmacists and equipping them with the necessary training is yielding exceptional results. The future path is to foster community engagement in preventative strategies. The essence of clinical leadership can ultimately be summed up in the vision provided by Jatinder Harchowal, the Chief Pharmacist at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, as he says: “Leadership is when it is easier to do nothing”. Therefore, leadership is not simply a title, but merely an action.

References

(1) Care Quality Commission, Public Health England, National Health Service (2014). Five Year Forward View. England: NHS, pp.22-23. [Accessed 3 Oct. 2017].

(2) NICE guidelines NG5 (2015), Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes, London (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk. [Accessed 3 Oct. 2017].

(3) The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2013). Medicines Optimisation: The evidence in practice. [online] Available at http://www.rpharms.com/promoting- pharmacy-pdfs/mo—evidence-in-practice.pdf [Accessed 3 Oct. 2017].

(4) Carter (2015), Review of Operational Productivity in NHS Providers (interim report), London, [online] Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/434202/carter-interim-report.pdf/ [Accessed 3 Oct. 2017].

(5) NHS (2016). Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) Guidance for 2017/19. [online] England.nhs.uk. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/ [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

(6) The Cancer Vanguard Website. (2017). The Cancer Vanguard. [online] Available at: https://cancervanguard.nhs.uk/ [Accessed 3 Oct. 2017].