Prof Michal Alberstein, PI of the European Research Council-funded project ‘Judicial Conflict Resolution’, discusses her view on the future of the judicial role

The roles of judges in the era of “vanishing trials” – an era in which settlements and plea bargaining far outnumber full and final verdicts – are largely unknown. With the support of a generous grant from the European Research Council (ERC), we are conducting a five-year comparative study in three jurisdictions – Israel, England & Wales, and Italy – to clarify their current and potential roles and to thus help litigants navigate their way through the legal system.

The goals of this wide-ranging research project, the Judicial Conflict Resolution (JCR) Collaboratory, are threefold. First, it seeks to empirically describe the role of judges in promoting settlements, the nature of this involvement, and the various alternative dispute resolution tools employed by judges in this process. Second, the research seeks to advance theory concerning the new roles performed by judges in the courtroom, which will lead to the conceptualisation of a new jurisprudence of Judicial Conflict Resolution. Finally, the research seeks to develop policy recommendations and training schemes for judges, and to establish norms and regulations for the process of reaching settlements.

We have found that in the three systems roles of judges have changed as the legal systems strive to minimise the cost and time of legal proceedings. The aspiration for efficiency has led to an emphasis on the pre-trial stage (where sides are encouraged to settle), abbreviated trials, conciliation hearings, and referral to mediation and other alternative dispute resolution processes to reduce the caseload. In the common law systems (Israel, England & Wales), the large majority of cases are disposed of without trial. In Italy, which has a civil law system, we found that this process is beginning, and creating an interesting model of jurisprudence – in which there is a sharp distinction between justice achieved through adjudication and mediation.

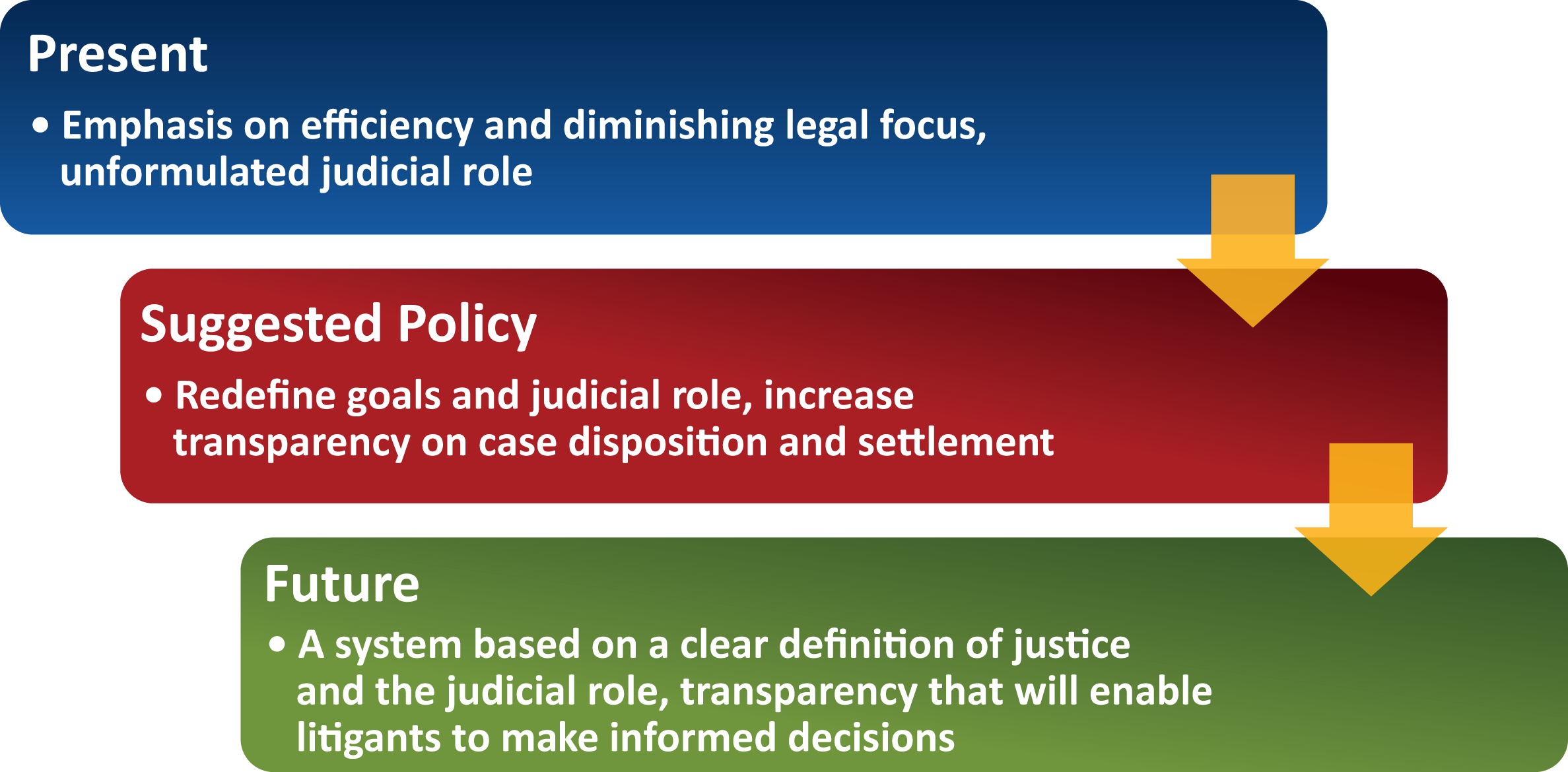

While judicial roles have changed dramatically due to the vanishing trial phenomenon, they have not been explicitly formulated in legislation, and are not documented in official public legal records. We found that relevant state-provided data are sorely lacking. We filled these gaps in data through courtroom observations and interviews, as well as a meticulous statistical docket analysis.

In the pre-trial stage – which is often the closest that sides embarking on a legal procedure will ever get to trial in adversarial systems (e.g., case management conferences in England and Wales and pre-trial conferences in Israel), judges use a mix of tools that can be proactive and are mostly characterised by a narrow focus on costs and time. In Israel, these practices also include risk assessment and prediction. In Italy, following reforms to reduce a severe backlog of cases, judges are issuing judicial conciliation proposals and mediation orders during trial.

In most cases, in the three systems, judges will not use a broad spectrum of relevant and available conflict resolution methods. This state of affairs raises the question as to the place of efficiency (in terms of time and cost) in legal systems. While efficiency is important and justice deferred is actually justice denied, it does not seem sufficient as an overarching goal of a legal system. In Israel and Italy, no articulation of a concrete perspective of justice exists while constant reforms have focused on effective case management and pre-mediation mandatory meetings. In England such an attempt to clarify the goals of the legal system has been made – with a focus on “access to justice” together with the designation of adjudication as a “last resort” for civil law cases.

However, this formulation was made in the shadow of severe budgetary cuts to the civil justice system, and many litigants, including the disadvantaged, are at times barred from entering the court due to high costs. Mediation, too, falls short of its promise, and is largely influenced by the institutional drive for efficiency and settlement rather than the interests and needs of the parties. Within the two adversarial cultures examined, neither adjudication nor substantial ADR are common – the public loses both ideals.

Interestingly, we found that in Italy, in which the judiciary is inspired by the inquisitorial tradition, the dichotomy between mediation and adjudication is more preserved and judges maintain their roles as legal truth seekers, while acknowledging the other dimensions of conflict that mediation can address.

Following our research findings thus far, our recommendations as to the future of the judiciary are as follows:

Coherent dispute system design of the court system. The desired goals of the legal system, including the role of judges, should be discussed and explicitly framed and implemented through theory building and articulation of values. Theorists and policymakers may experiment with conflict resolution as the dominant goal, making adjudication an alternative door, and considering whether judges are active leaders in the system or have a different, supplementary role. Following this theory-building, judges should be trained accordingly.

Increased transparency and data collection. Accurate data should be collected and made available so that parties (whether they be consumers or tort claimants) can make informed choices and have a real perspective on what happens when settlements are the norm. This follows our finding that data on rates of settlements and outcomes of legal verdicts are mostly inaccurate and inaccessible to litigants as they try to process their disputes. Full records of court settlement hearings and all forms of abbreviated trials should also be made available. The electronic legal file should become a universal framework to collect data in ways that will enable parties to learn about the reality of legal settlements, and for scholars to compare among legal systems. This will also have an effect on the judicial role by reducing the caseload.

Ultimately the determination of judicial roles should be a result of a thorough deliberation among the various stakeholders in the legal system. A conscious decision and a push for transparency is much better than the currently abstruse reality.

*Please note: this is a commercial profile.