With eyewitness awareness of how six million Jewish people lost their lives, aging Holocaust survivors have carried an impossible burden – now, researchers are attempting to document the lifelong impact of trauma

Here, I look at research investigating the trauma of aging Holocaust survivors by Associate Professor Yoram Barak, at the Brain Health Research Centre.

The slow dehumanisation of the Jewish people

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, the trajectory of millions of lives was cruelly and permanently altered. In those first few months, thousands of Jewish people were murdered. Then, Polish Jewish people were forced into segregated neighbourhoods – later described as “ghettos”.

The “ghettos” were created with death in mind – conditions were terrible, with severe illness and starvation encouraged by the Nazi leaders who designed this infrastructure. The German public in general supported these actions, which happened after centuries of intentional anti-Semitism.

After the Jewish community became appropriately marked as a threat in the minds of the public, Nazi leaders found their genocide possible to implement. Modern day anti-Semitism is a chilling parallel to this history of slow dehumanisation.

Three years later, the ‘Final Solution’ was implemented with increased urgency. The first murder-camp was established in 1941, in an ancient Polish city called Chelmno.

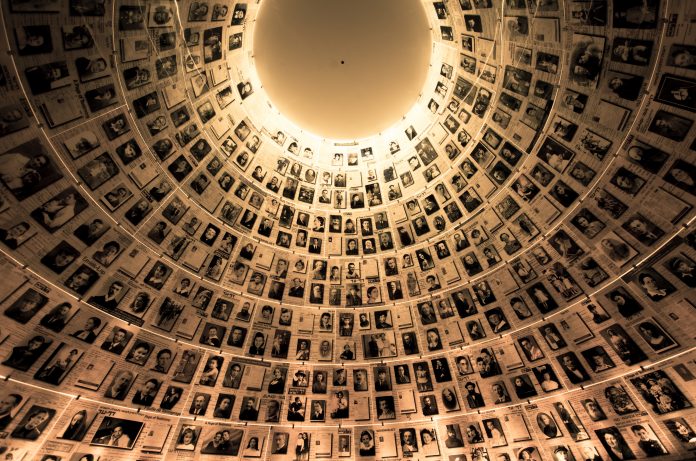

By 1945, the known total of lost Jewish lives was 6 million. And there were 500,000 known survivors.

The traumatic impact of talking about the Holocaust?

While history reflects on the number of lives lost, and today, we honour survivors by listening to their stories – what about their trauma?

It is an individual choice of any Holocaust survivor whether they want to discuss all they’ve seen. When memorial days come and go, these individuals are given much-deserved attention and platform for their experiences. As an audience, we cherish their strength, while we hate what caused their strength. We collect their memories, of the before-times, of childhoods, of their lost family members and friends and neighbours.

Even of their lost futures, as survivors reflect on how life was taken from even the still-living. Henry Kichka, an Auschwitz survivor, explains to the BBC that: “You did not live through Auschwitz. The place itself is death.”

What is the psychological impact within the human brain, of holding and recalling these memories?

In re-telling his story, he exposes his mind to revisit the horrors of the camp. This fierce feeling of duty is explained by his daughter Irene, who said: “It’s necessary to have books, films and documentaries, of course. But when you hear it from someone’s own lips in their own voice, it stays in your head. You never forget.”

Professor Yoram Barak wondered if trauma lasts forever

He explains that PTSD remains a relatively obscure disorders, in the sense that there is not enough research about the minutiae of what happens to people and why. Prolonged traumatic experiences are accepted to create PTSD, but the way that this disorder changes throughout a lifetime is relatively vague.

In his paper, he looks at a study by Koren and colleagues, which suggests that PTSD is rampant one to three months after trauma – then plateaus. So, the experience of trauma could theoretically become moderately steady after the experience itself.

Barak writes: “Is this “plateau” phase lifelong? Do PTSD symptoms remain severe and disabling throughout the life cycle? Are maturation, aging, and reintegration into society factors that affect the course of PTSD?”

To create a more specific psychological insight on the lifelong impact of trauma, Professor Barak turned to an academic psychiatric institute in Israel for participants.

‘Subject to extreme and massive psychic trauma in their youth’

He found that physical ill health, retirement, loneliness, comorbid psychiatric illness, anniversaries, reunions, and use of alcohol and psychotropic medication are all factors that can re-trigger symptoms of PTSD.

It seems that, for many of the veterans, the PTSD has lasted for 50 years. Though, there was a “masking” of intrusive symptoms in their midlife stage. Could Holocaust survivors expect the same kind of plateau?

Barak explains that “for them, aging is a phase of severe crisis,” as it means “in later life, when friends are gone, the need to share with others becomes urgent; to bear witness is vital.”

The results of his conversations with 61 Holocaust survivors

So, 41 women and 20 men spoke to the Professor about their experiences – not just their initial trauma, but their lives afterwards – especially when they undergo a secondary disorder to their PTSD.

He found that 91.8% of these individuals experienced chronic PTSD. They were also experiencing another disorder, either schizophrenia (52.5%), affective disorders (27.9%) or other psychotic disorders (19.6%).

He explained that: “It is difficult to say whether the occurrence of PTSD in our group represents lifelong suffering, beginning close to the end of the traumatic experience and persisting for more than 50 years, or whether it represents a phase of symptomatic reactivation occurring in WWII veterans in their old age.”

Essentially, it was hard to understand if these individuals ever experienced a break in their PTSD that later came back, or if they maintained the same level of intrusive thinking throughout their lives. The study also suggested that intrusive symptoms were more present in this group, than avoidant ones. Thoughts, memories, and sensations actively came to haunt these patients – as opposed to a numbing ‘masking’, possible in other experiences of PTSD.

In the paper, he describes a particularly harrowing moment: “One of our patients only described a cannibalistic experience during extreme starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp when in the manic-psychotic phase of his bipolar disorder.

One of our patients only described a cannibalistic experience during extreme starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp

“While euthymic or depressed, he was unable to recall or recollect this experience.”

PTSD in combination with psychosis leads to lifelong illness

The results indicate that survivors who only have PTSD can be successful – historicising their memory via their brain’s capacity to experience avoidant symptoms and mask the past. This means establishing a continuity between early, positive pre-Holocaust memories, through traumatic memories during the Holocaust and memories of re-establishing the fabric of life in the post-Holocaust period.

This means a lot of mentally draining activity, but this effort to re-organise memory can definitely work.

Memory becomes a “lifelong burden”

Sadly, the results of this investigation are bleak for individuals who live with both psychosis and PTSD. It was found that they experience lifelong debilitating illness, as they are unable to stop experiencing the memories as if they are connected to the present moment. Memory becomes a “lifelong burden”, with the fragmentation of the ego happening to cope with this omnipresent knowledge.

Henri Kichka, a survivor not involved in this study, also reflected on how anti-Semitism continues in the present. He asked: “Why make enemies of the Jews? We have no guns, we are innocent.

“I don’t understand why people hate us so much.”