Bethany Torr, Campaigns and Advocacy Officer at Leukaemia Care explores how outcomes for acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) can be improved

Each year around 3000 people in the UK are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), affecting children, young adults and incidence significantly increasing from the age of 50 years old. Unfortunately, late diagnosis rates and a lack of treatment options for those unable to tolerate intensive chemotherapies are contributing to poor survival.

It is well-known that early diagnosis of cancer can improve outcomes and for AML there is no exception. As an acute, or quickly progressing cancer, the immature leukaemia cells take up space within the blood and bone marrow and the number of healthy, functioning cells rapidly decline. Patients can go from feeling relatively well to being dangerously ill in a short period of time and it is, therefore, vital that people know the signs and symptoms to look out for.

Unfortunately, the signs and symptoms of acute myeloid leukaemia are vague and often attributable to common illnesses. In a 2016 Leukaemia Care survey, the top symptoms reported by patients prior to diagnosis were: fatigue, feeling weak or breathless, easily bruising or bleeding, fever or night sweats and pain in the joints or bones.

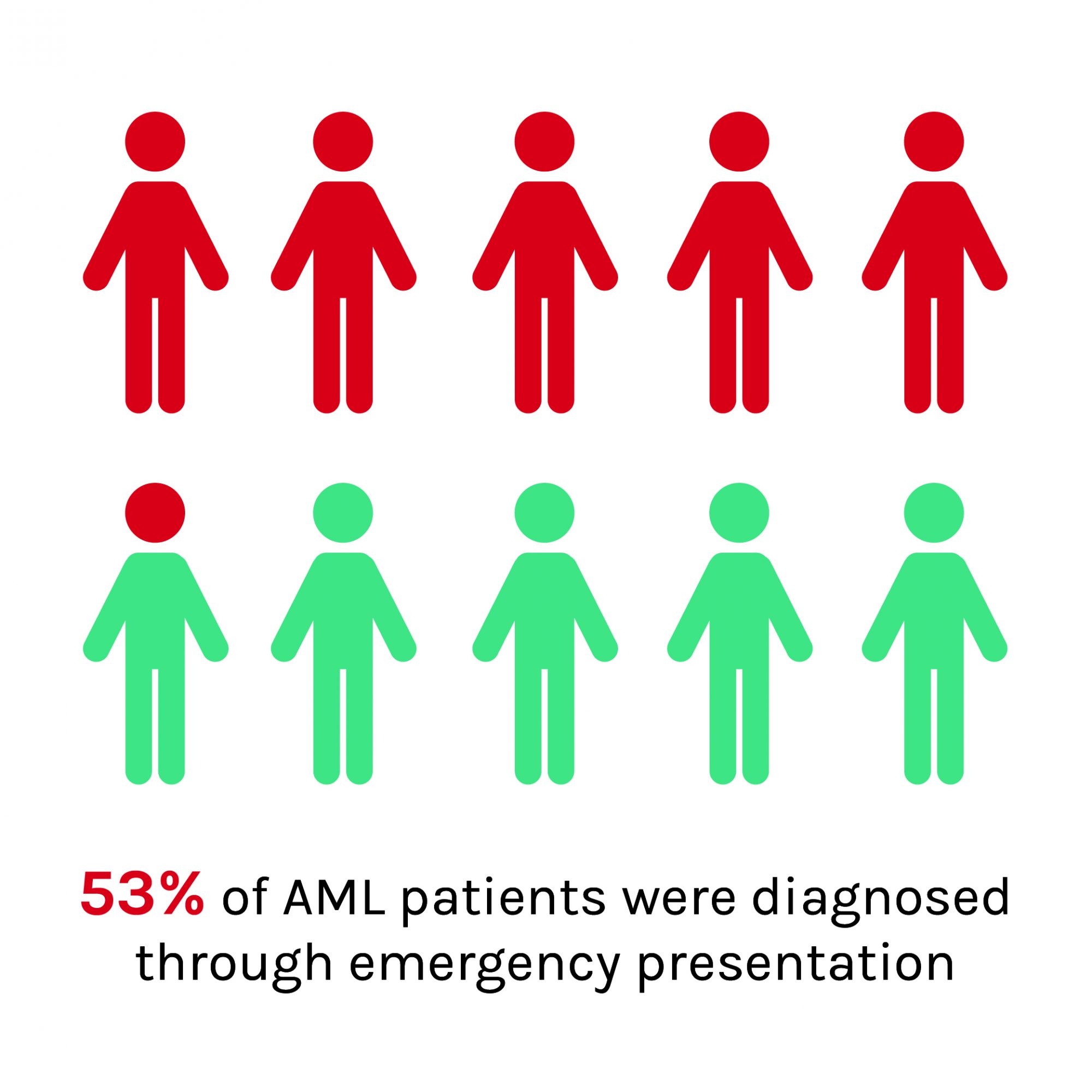

Despite nine in ten patients experiencing symptoms, 84% were not expecting to be diagnosed with cancer. Demonstrating that people are not aware that these symptoms are attributable to a blood cancer and are more likely to delay in visiting their GP. This could be significantly contributing to the extremely high levels of emergency presentation of AML (53% of all patients between 2006 and 2015) compared to the average for cancer (22%).

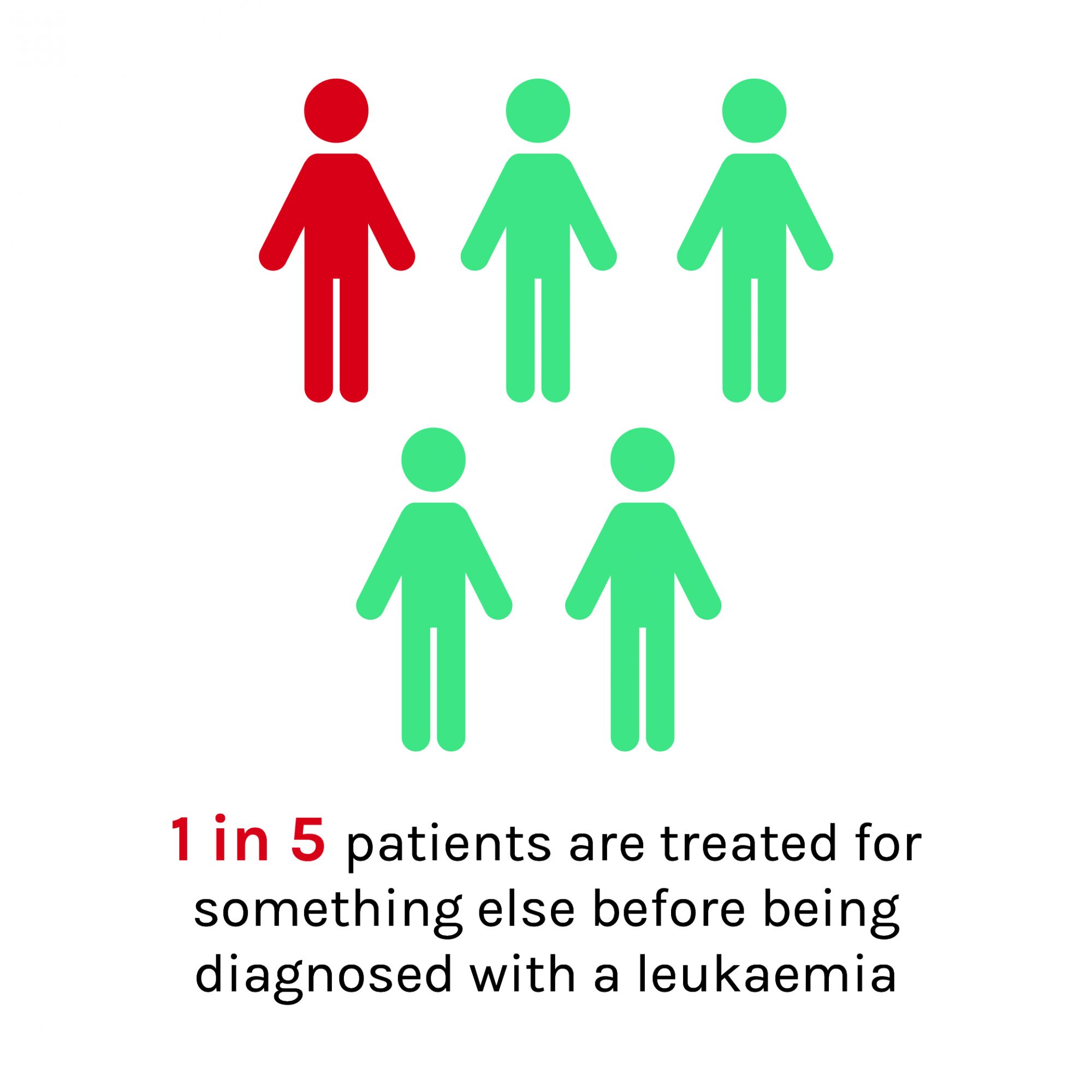

Not only does low levels of symptom awareness in the public cause delays in presentation, but there are also significant delays in diagnosis at the primary care level.

A GP may only see one case of leukaemia every four years and with the symptoms being like those of more common conditions, being able to identify potential cases of AML can be difficult. Leukaemia Care’s survey revealed that more than 1 in 5 patients are treated for something else before being diagnosed with a leukaemia. This adds substantial delays in the patients receiving the urgent treatment required for AML, which could be easily avoided by a simple blood test.

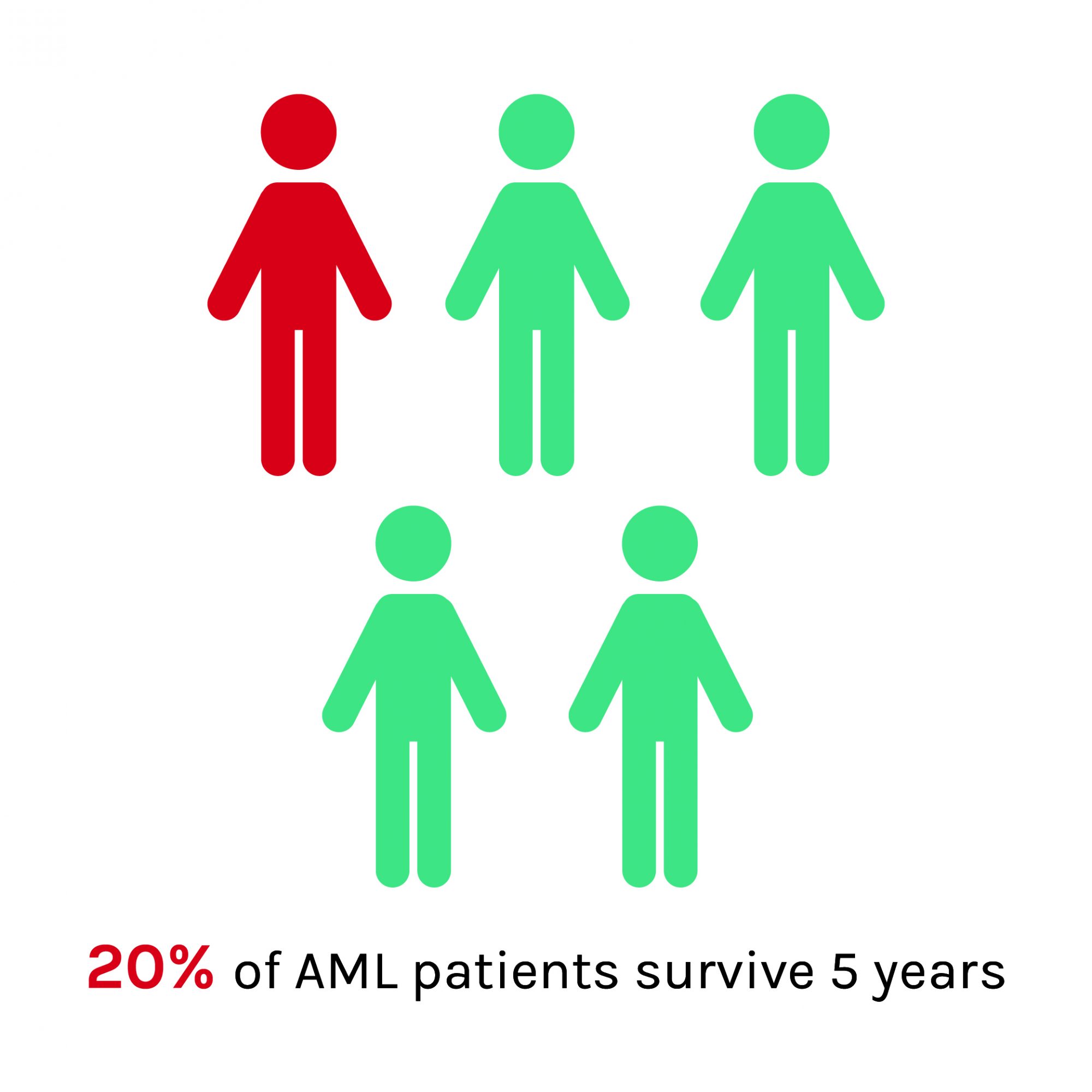

Leukaemia Care is working to both improve public awareness of leukaemia and equip GPs to better recognise potential cases, in a bid to improve early diagnosis of leukaemia and save lives. Late diagnosis is, however, not the only factor contributing to the low survival rates for AML, estimated to be around 20% of patients surviving five years. Survival rates are directly associated with age and this is a consequence of older patients often not being fit enough to tolerate the intensive, non-specific chemotherapy treatments currently used for AML.

With the rise of genetics over the last few decades, there have been key improvements in the knowledge of what causes AML. Cancers are driven by genetic changes that cause the loss of normal control over cell division and cell function. There are several different genetic changes identified in the myeloid cells that are associated with AML and these can be indicators into the response to treatment and hence prognosis of a patient.

It is, therefore, better for the clinical treatment and management of AML to categorise it into subtypes, based upon the genetic mutations driving the leukaemia. As knowledge and understanding of the subtypes increases, more targeted therapies are being developed. This, in theory, means fewer side effects and a greater chance of successful treatment, by targeting the AML cells specifically. This will be of importance to the large proportion of older AML patients who are currently unable to have curative chemotherapy.

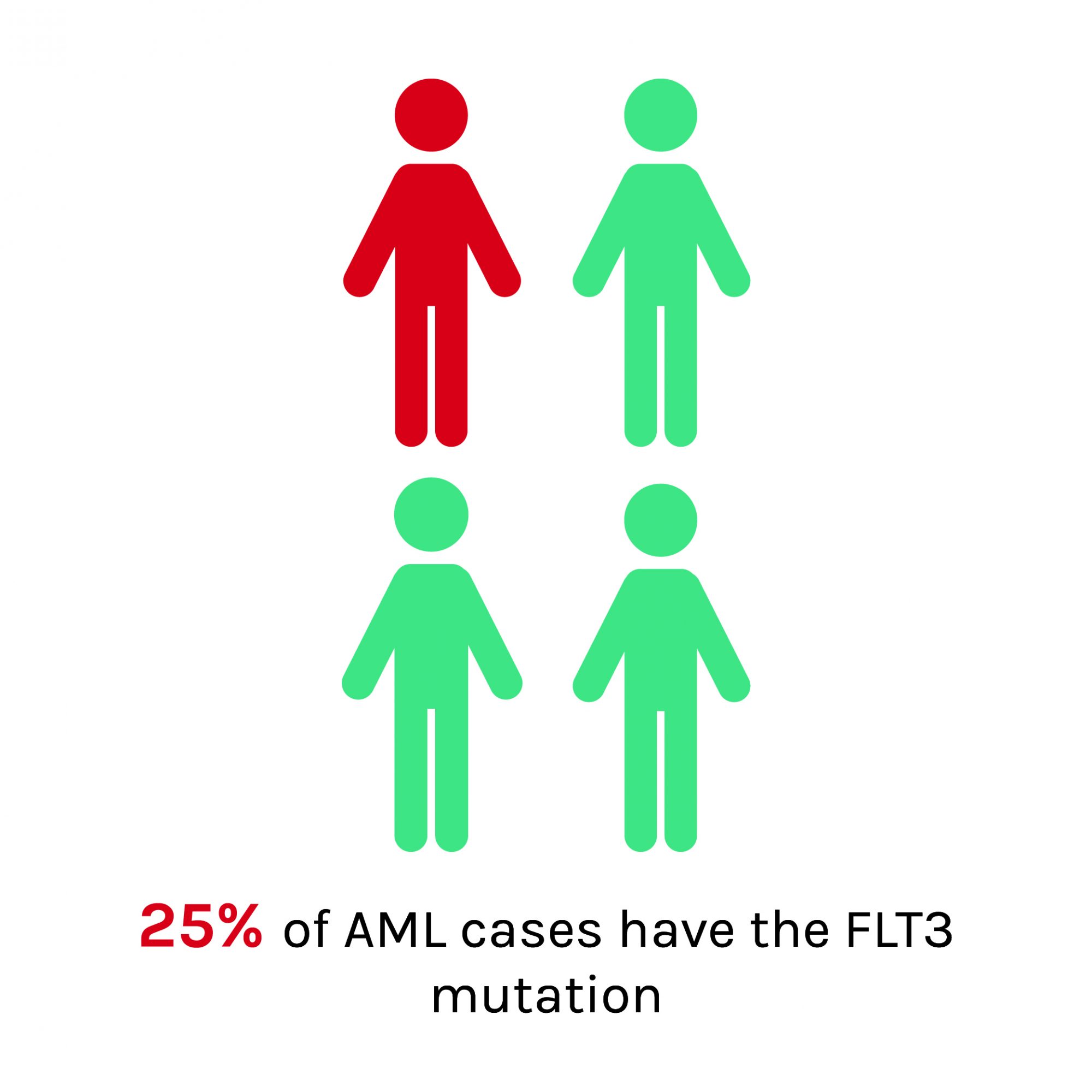

Recently, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved the first targeted therapy for AML, midostaurin, for use within the NHS. This drug is a small-molecule kinase inhibitor, that works specifically to block the FLT3 tyrosine kinase receptor. FLT3 mutations are the most common mutation driving AML, found in around 25% of cases. In clinical trials, when midostaurin was used in combination with chemotherapy, results demonstrate prolonged survival and better quality of life for patients.

Promisingly, building on the increasing knowledge of AML subtypes and developing further targeted therapies is likely to improve the outlook for more patients in the future. In the meantime, it is essential that work is done to raise awareness, improve early diagnosis and ensure patients are receiving appropriate cytogenetic testing to increase knowledge of AML subtypes.

Bethany Torr

Campaigns and Advocacy Officer

Leukaemia Care

Tel: +44 (0)1905 755 977

Bethany.Torr@leukaemiacare.org.uk

www.twitter.com/LeukaemiaCareUK