Abundant wind resources, ever more efficient offshore wind turbines and the shallow North Sea provide favourable conditions for turning green power into the reliever for natural gas

Energy policies have long envisaged such a green hydrogen industry. The Esbjerg Declaration dictated a 20-gigawatt green hydrogen production capacity in Denmark, Germany, Holland and Belgium by 2030.

This will require a surge in offshore wind capacity from an industry struggling with profitability. The supply chain is heavily affected by inflation, and decision-makers await better market conditions or outright cancel projects. The Oostend Declaration recognised the bottlenecks in the supply chain and considered the European Commission’s Green Deal Industrial Plan and the Net-Zero Industry Act to enhance the competitiveness of Europe’s net-zero industry.

Green hydrogen in Europe

The environmentally cautious consumer represents a fast-paced shift in the demand for products with a lower carbon footprint. Hence, the plan from the European Commission is plausible and should gain the confidence of the decision-makers if green energy is available. Green electrons must be available to develop the hydrogen economy, and delays to projects for whatever reason juxtapose both the environment and the competitiveness of the industrial clusters in Europe.

The question remains whether the other pathways with pink, yellow and blue hydrogen allow for a faster green transition and minimisation of the carbon footprint of manufactured goods. Key insights from the European Hydrogen Partnership show that there were 476 hydrogen plants in operation in 2022, and they produced 8.23 Mt. Refining and ammonia production depicted the majority of the demand for hydrogen. Still, the European Union is ambitious to produce 10 Mt and import 10 Mt hydrogen by 2030. Hence, multiple other industries are envisaged to create the demand for hydrogen, albeit production and distribution will vary when considering the cost of the transformation.

What about green hydrogen fueling infrastructure?

Consider the requirement for fueling stations for the rising number of fuel cell vehicles and the practicality of distributing hydrogen. More than 25,000 trucks are registered in Denmark, and a large percentage are used for import and export from neighbouring Germany. Therefore, the hydrogen fueling infrastructure in the countries should be developed simultaneously in Europe to allow for a seamless transition to zero-emission fuels. Thus, the timing and the requirement for implementing hydrogen fueling stations and fuel cell trucks must be evaluated.

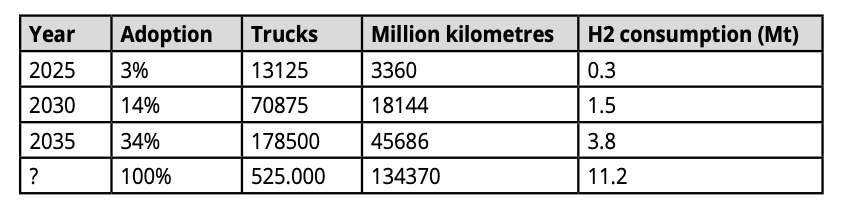

The European Hydrogen Partnership states that emerging applications use 3% of the current hydrogen production. However, it could be evaluated for a system with clear boundaries to evaluate the practicability of adapting zero-emission road haulage in a complex. The United Kingdom (UK) can be seen as such a system with more than half a million trucks on the roads. Here, one may argue that the early adoption has commenced, but following the strategies from the UK, the target is that 70% of all trucks sold in 2030 should be emission-free.

Could fuel cell trucks be implemented?

If fuel cell trucks are implemented in the next decade, demand may run beyond availability. The numbers below portray the practical adaptation curve. From this, it may be noted that hydrogen production needs to increase rapidly to justify the political plans. Still, it also raises the question of hydrogen production, distribution, and end-use.

In context to the distribution of hydrogen for fueling stations, it should be noted that the 8,380 gas stations available in UK today would need 454 trucks to refuel the gas stations daily in 2035. The cost of distributing hydrogen is computed to 7% of the cost of hydrogen, compared to diesel, which has a distribution cost of 1,4%.

Therefore, rethinking distribution is imperative. The concept of hydrogen backbone becomes relevant, albeit only if considered in relation to transport networks and significant corridors. Equally important is the role of ports in this hydrogen network, as a large number of trucks deliver to the ports on a daily basis, given the volumes in short-sea shipping. Fueling in the port optimises the hydrogen distribution need and possibly lowers the cost.

This also reverts the question to the production of hydrogen. In context to the countries around the North Sea, the interest sphere of blue and green hydrogen projects may be intertwined. The synergy of hydrogen produced with electrolyses or reformers carries similar requirements for infrastructure in the form of ports and pipelines. Both green and blue hydrogen must be considered to scale hydrogen availability. Therefore, carbon capture and storage become one of the predecessors that carry similar needs to ports and pipeline infrastructure.

The fight for climate change is entrenched in businesses today, but developing ports and pipelines may not be the decision made in one board room. These projects are of common interest and benefit multiple entities. The models developing ports have been refined over centuries. Still, the green transition almost presents a paradigm shift as fueling trucks entering the ports and future zero-emission ships servicing the European corridors must inevitably be embedded in any strategic decisions.

Build the infrastructure for the green transition

In the future, ports must be able to handle green fuels, and therefore, they must consider their position in the industrial ecosystem, which encompasses hydrogen production. Given the shared interest of producers, ports and distributors, new business models and finance options must be developed jointly to build the infrastructure needed for the green transition. The actors must embark on such a new form of collaboration to build infrastructure.

The present jockeying for project financing and future returns and the Darwinian-style funding schemes seem counterproductive. The need for energy transition in the transport sector requires the actors to collaborate on new business models, which should be rewarded based on timely execution and collaborative efforts, given that we all share the same worldview of a speedy green transition.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.