Irene Kriesi and Miriam Grønning explain how initial vocational education and training in Switzerland facilitates fast and smooth labour market entry, but also offers heterogenous career prospects

In Switzerland, initial vocational education and training (IVET) is the dominant type of upper-secondary education. About two-thirds of all young people in Switzerland enter IVET after completing compulsory school. The vast majority go into so-called “dual IVET”. It is largely workplace-based, and learners spend three to four days per week in a training firm and one or two days at a vocational school. To meet all the educational objectives of their training occupation, the trainees, furthermore, spend some time in inter-company courses, where they learn and practise occupational skills that their training company does not cover.

Previous research has shown that the vast majority of IVET graduates find matching jobs quickly after earning their diploma (e.g., Schweri, Eymann & Aepli 2021). Furthermore, their employment prospects are better than those of workers with no or general upper-secondary education and comparable to those of workers with tertiary-level degrees. However, the latter do earn higher average wages than IVET degree holders (Aepli et al. 2021).

Heterogeneity of IVET

Although the average labour market outcomes of workers with IVET diplomas are generally favourable, our research shows that there is a lot of heterogeneity within IVET that is masked in studies treating IVET as a homogenous type of education. This is little surprising if we take into consideration that Swiss IVET includes about 240 different training programmes. They cover a wide variety of occupations from all sectors, such as, for example, hairdressing, nursing, waitressing, plumbing, carpentry or occupations such as retail specialist, laboratory or information technologist. The training programmes are based on nationally binding occupation-specific training ordinances and curriculum frameworks issued by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation.

Despite this high level of standardisation within programmes, heterogeneity between programmes is large. This pertains not only to the occupation-specific content, but also to the duration, the academic requirement level or the degree of occupational specificity. Occupational specificity refers to the extent to which education programmes provide practical skills and knowledge that are mainly useful in a specific occupation. Some programmes impart a high proportion of these skills, while others teach more general skills and knowledge that can be transferred between occupations.

General and occupation-specific education and training content in Swiss IVET programmes

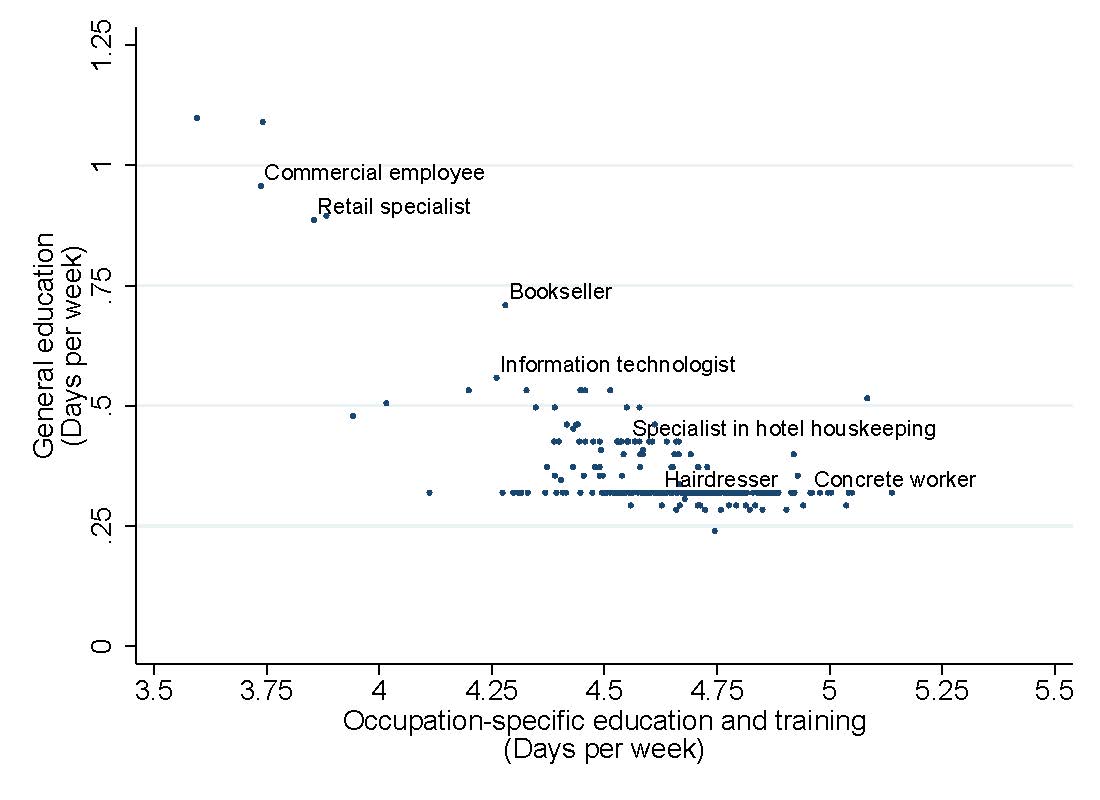

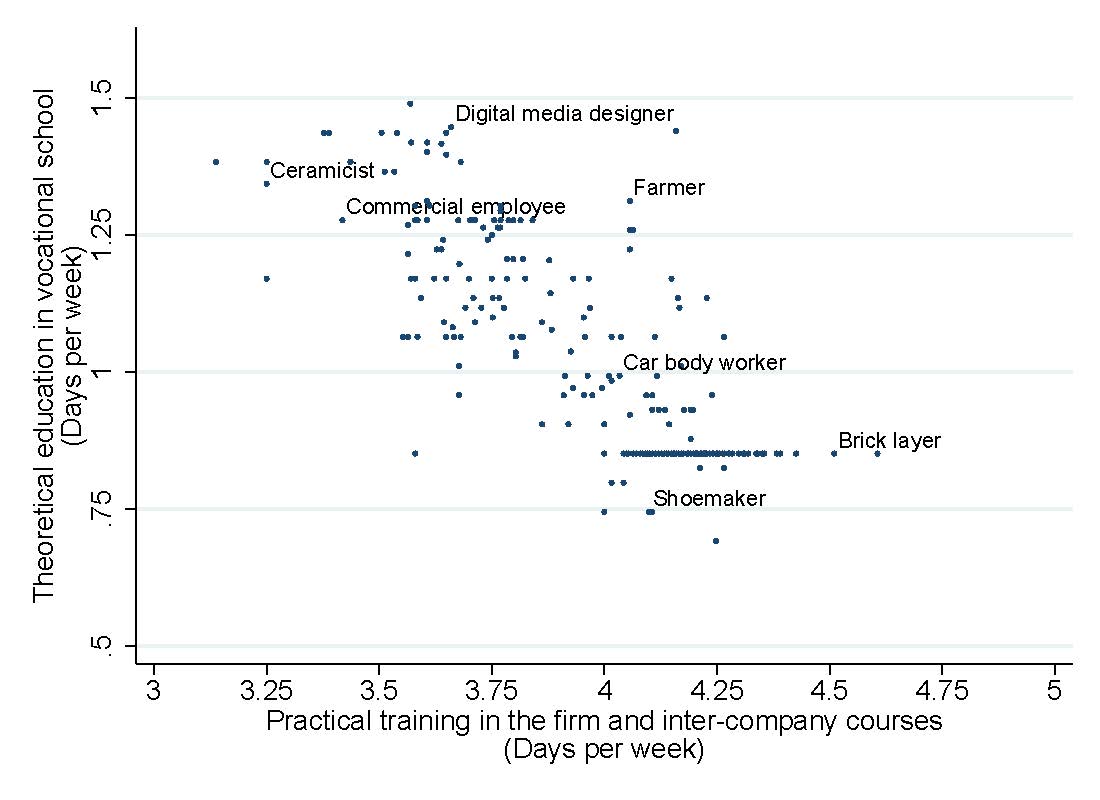

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the large differences within the regular three- and four-year programmes. Whereas, for example, commercial or retail apprentices are taught almost a day per week in general education, such as language and communication skills, politics, law and economics, the training for occupations such as hairdressers or concrete workers focuses strongly on occupation-specific education and teaches approximately 2.25 hours of general education per week only. In a similar vein, the time spent at vocational school and in the training firm differs considerably. Digital media designers, for example, spend almost 1.5 days per week at a vocational school and 3.5 days in the firm. At the other end of the scale, brick-layers or shoemakers spend less than a day per week at vocational school.

Characteristics of IVET programmes and career prospects

Against this background, we were interested in whether such differences in the taught skills affect young IVET diploma holders’ school-to-work transition and subsequent careers. Our findings show that programmes with a lot of practical occupation-specific training facilitate the school-to-work transition by increasing the probability to find a matching and well-paid job. The likely reason is that a lot of practical training increases a worker’s initial productivity and decreases the need for on-the-job training. However, our findings also show that comparatively large proportions of general education within IVET go along with steeper wage increases, a higher probability to enter tertiary-level professional training and a higher probability for occupational upward mobility (Grønning 2021; Grønning, Kriesi & Sacchi 2020; Sander & Kriesi 2021). These results suggest that general education facilitates learning and mobility, thus making workers more flexible to adjust to the fast-changing skill demand.

In summary, the findings show that Swiss VET offers fairly good career prospects. Its high degree of occupational specificity facilitates young people’s labour market integration. However, the results also highlight that general education should not be neglected within IVET as it provides skills that are transferable between jobs and occupations. In dynamic labour markets, it will become increasingly important for workers to be able to adapt flexibly to changing skill requirements. General skills and education support young people in reaching this aim.

References

- Aepli, M., Kuhn A. & Schweri J. (2021). Studie zum Wert von

- Ausbildungen auf dem Schweizer Arbeitsmarkt. Zollikofen, Swiss Federal University for Vocational Education and Training SFUVET.

- Grønning, M. (2021). Institutional Characteristics of Upper

- Secondary Vocational Education and Training in Switzerland: How Do They Affect VET Diploma Holders’ Early Labour Market Outcomes?

- Dissertation, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover, Hannover.

- Grønning, M., Kriesi, I., & Sacchi, S. (2020). Income during the early career: Do institutional characteristics of training occupations matter? Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100495

- Sander, F., & Kriesi, I. (2021). Übergänge in die höhere

- Berufsbildung in der Schweiz: Der Einfluss institutioneller

- Charakteristiken des schweizerischen Berufsausbildungssystems. Swiss Journal of Sociology 47 (2), 305-332. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjs-2020-0031

- Schweri, J., Eymann A. & Aepli M. (2020). Horizontal mismatch and vocational education. Applied Economics 52 (32), 3464-3478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2020.1713292.