Professor Carlos Aguiar, Chair of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Communication Committee and spokesperson for Heart Failure, outlines the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure

Heart failure (HF) is associated with reduced life expectancy, increased risk of hospitalisation and unplanned visits to the hospital, and impaired quality of life. (1) HF is an increasingly important public health problem, as well as a substantial and continuously growing socio-economic burden. (2,3) It affects one to two of every 100 adults in the general population, and more than one in ten people aged 70 or over years are diagnosed with HF. The true prevalence of HF is likely closer to 4%, as it often goes unrecognised or misdiagnosed, particularly in older people. The absolute number of patients living with HF has been increasing, because of the ageing of the population, global population growth, improved survival after coronary events and HF diagnosis, and rising prevalence of HF risk factors. (4) Unsurprisingly, some countries have recently recorded a deceleration of the rate of decrease of heart disease mortality, partly explained by a rise in the age-adjusted mortality rate for HF. (5)

Nevertheless, significant advances in the diagnosis and management of HF have transformed HF into a condition that is both preventable and treatable for many patients. The new 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF provide up to date, practical recommendations to help health professionals manage patients with HF according to the best available evidence.

The new treatment algorithm for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) begins with the ‘fantastic four’ pharmacological interventions which every eligible patient should receive to reduce all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalisations. These are an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), a beta-blocker, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), and a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin). HFrEF patients should be prescribed all these treatments as soon as possible, and the doses should be up titrated to those used in the clinical trials (or else to maximally tolerated doses) in a timely fashion. The benefits of these pharmacotherapies appear early, hence delays in treatment optimisation can cause avoidable mortality and morbidity. Patients hospitalised due to HFrEF should have an early follow-up visit at one to two weeks after discharge to start and/or up titrate evidence-based therapy. Treatment optimisation should also be pursued in the less symptomatic, apparently ‘stable’ chronic HFrEF patient, because of the progressive nature of myocardial injury. (6)

Sudden arrhythmic death is responsible for a high proportion of mortality among patients with HFrEF, especially in those with milder symptoms. The risk of sudden cardiac death is reduced by several HFrEF treatments (namely beta-blockers, MRA and ARNI) that improve or delay the progression of heart disease, but these do not treat arrhythmic events when they occur. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) effectively correct potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias. An ICD is recommended to reduce the risk of sudden death and all-cause mortality in patients with symptomatic HF (in New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class II or III) of an ischemic aetiology (unless they have had a myocardial infarction in the prior 40 days), and a left ventricular ejection fraction £35% despite at least three months of optimal medical therapy, and provided they are expected to survive substantially longer than one year with good functional status. In non-ischemic patients otherwise fulfilling the same criteria, implantation of an ICD is now a class IIa recommendation (‘should be considered’).

The 2021 ESC guidelines have a total of 41 new recommendations and have modified 15 recommendations from the 2016 document. Learn more about what’s new in the diagnosis and management of HF here.

More on heart disease: How does it affect the U.S.?

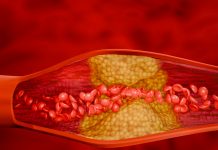

The term “heart disease” refers to several types of heart conditions. While cardiovascular disease is the biggest killer in Europe, accounting for four million deaths per year (47% of all mortalities) and costing the EU economy an estimated €196 billion annually, it is just as prevalent around the globe. It is the leading cause of death in the U.S., causing about one in four deaths, with the most common type being coronary artery disease (CAD), which can lead to heart attack.

Heart disease can often be “silent” and not diagnosed until a person experiences signs or symptoms of a heart attack, heart failure, or an arrhythmia. If someone is experiencing arrhythmia, they will have fluttering feelings in the chest (palpitations), whereas during a heart attack, symptoms may include:

- Chest pain or discomfort.

- Upper back or neck pain.

- Indigestion.

- Heartburn.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Extreme fatigue.

- Upper body discomfort.

- Dizziness.

- Shortness of breath.

Furthermore, symptoms of heart failure include shortness of breath, fatigue, or swelling of the feet, ankles, legs, abdomen, or neck veins.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (DHDSP) supports state, local and tribal efforts to prevent, manage, and reduce the risk factors associated with heart disease and stroke. The division supports and funds activities as part of several multi-program cooperative agreements, in which CDC provides additional guidance and support beyond simply overseeing and monitoring activities.

One example of a state programme administered through the DHDSP is WISEWOMAN, (Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for WOMen Across the Nation,) which was created to help women understand and reduce their risk for heart disease and stroke by providing services to promote lasting heart-healthy lifestyles. By regularly working with low-income, uninsured and underinsured women aged 40 to 64 years, the programme provides heart disease and stroke risk factor screenings and services that promote healthy behaviours.

References

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Bohm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599-3726.

- Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1342-1356.

- Hessel FP. Overview of the socio-economic consequences of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021;11(1):254-262.

- Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I, Hobbs FDR, Taylor CJ. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1306-1325.

- Sidney S, Go AS, Jaffe MG, Solomon MD, Ambrosy AP, Rana JS, et al. Association Between Aging of the US Population and Heart Disease Mortality From 2011 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:1280-1286.

6. Sabbah HN. Silent disease progression in clinically stable heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(4):469-478.