Here, the regulations on the marketing of unhealthy foods to kids are discussed as critical to reducing obesity

A Growing, Global Obesity Epidemic: With over 250 million children overweight or obese, with rapid growth experienced in Low- and middle-income countries.(1-4) Even at a young age, obesity has serious health consequences, harming nearly every organ system and disrupting hormones that control blood sugar and normal development.(4-8) Carrying excess weight during childhood and adolescence can take a serious social and psychological toll, with increased risks for depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, peer bullying, eating disorders, or poor performance in school.(9-16)

A Major Cause: Marketing to Children:

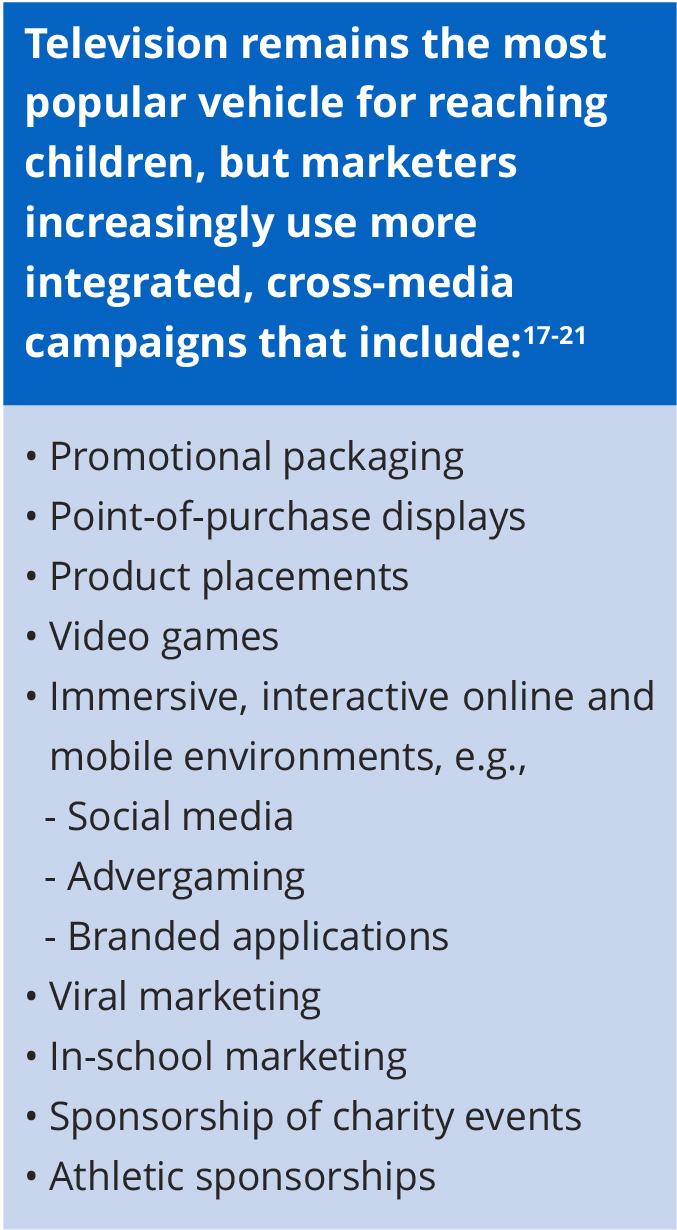

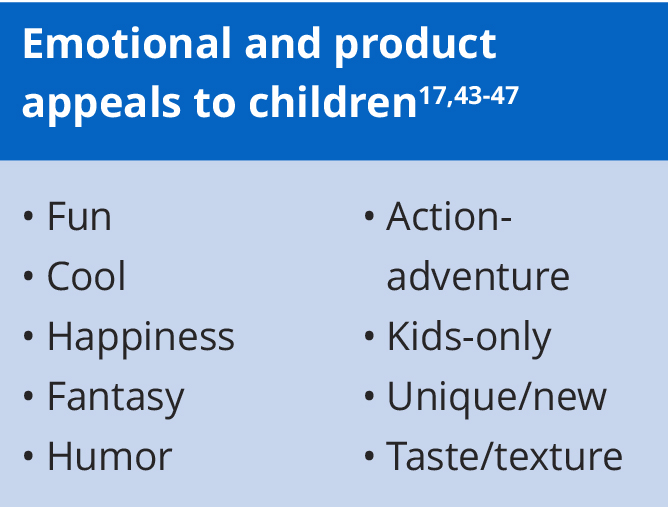

The World Health Organization and other major health organizations worldwide point to children’s exposure to pervasive, unhealthy food marketing as a significant risk factor for childhood obesity.(7,17,22-27) Foods and drinks are promoted to children more than any other product type and in far greater proportion than to adults.(28) Children are exposed every day to food marketing where they live, learn, and play – on TV, at school and sports practice, in stores, at the movies, on mobile devices, and online.(18,27,29,30) There is a vast literature summarising the role of advertising in children’s TV. A 2019 study of TV advertising in 22 countries around the world found, on average, four times more ads for unhealthy foods and drinks than healthy ones during all TV and 35% more unhealthy food ads during children’s peak viewing times.(31) While TV has historically been the medium of choice to reach children, marketing via newer online, mobile, viral, and social media has increased considerably in recent years.(19,27,32,33)

The majority of promoted food products are calorie-dense and nutrient-poor, with added sugar, saturated fat, and sodium well above recommended levels (e.g., sugary breakfast cereals, soft drinks, candy, salty snacks, and fast foods).(4,17,18,27,29,30,34-42)

Food Marketing Leads to Poor Diet and Obesity:

Marketing to children can have lifelong consequences, as childhood eating habits and preferences persist into later life, and the risk of overweight children becoming overweight adults is estimated to be at least twice that of normal-weight children.(28) Children are extremely vulnerable to food marketing. Developmentally, they are highly impressionable, cannot yet recognise advertising intent, lack nutritional knowledge, and are motivated by immediate gratification rather than long-term consequences.(25,27,38)

Food companies target children:

(1) To entice them to spend their own money on promoted products, (2) To exercise influence over what parents buy (via “pester power” or purchase requests), and (3) To cultivate brand loyal early in life, resulting in lifelong financial rewards for companies.(4,17,27,38,48-51) An extensive body of research consistently shows that: Marketing increases children’s awareness, recognition, and recall of brands and begins to affect them as early as preschool.(4,17,27,38,51-54); Repeated exposure to marketing forges positive brand associations and preferences – not just for promoted products, but for entire categories of junk food.(17,30,51,55-57); and Time spent watching TV and exposure to unhealthy food advertisements on TV are associated with children consuming more fast food,(58) more of the advertised foods (which are overwhelmingly unhealthy), and more calories.(59-62); and Children consume more of promoted products and develop lasting preferences for them that play a role in forming their self-identity and lifelong eating habits.(17,38,51,56,63,64)

The Need for Comprehensive Marketing Restrictions:

Children’s near-constant exposure to marketing for foods and drinks that misalign with their recommended diet is inherently unfair and exploitative, and it undermines parent, school, community, and government efforts to raise healthy children and prevent overweight, obesity, and costly disease.(4,65); The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child – ratified as international law by nearly every country in the world – affirms that children have a fundamental right to a healthy childhood, free from economic exploitation.(4,66)

Protecting children and adolescents from unhealthy food marketing is a cost-effective way to improve their chances of living a long, healthy life while also to reducing the mounting health care costs associated with non-communicable diseases worldwide.(21,67) Global leaders including the World Health Organization,4,20 Pan American Health Organization,(22) European Union,(68) and World Cancer Research Fund,(69) among others,(27,57,70) unequivocally recommend protecting children from exposure to unhealthy food marketing as a crucial step in stopping the rise of childhood obesity – by restricting or banning marketing targeting or viewed by children, by improving the nutritional profile of promoted products, or by both means.

Example of Strong Regulation: Chile

Chile has enacted the most comprehensive set of policies to date aimed at improving population diet and reducing chronic diseases,(71-73) including two complementary laws requiring front-of-package warning labels and restricting marketing for unhealthy products that do not meet specific nutrition criteria: The Chilean Food Advertising and Labeling Law (implemented June 2016),(74,75) wherein products with added sugar, salt, or saturated fat that also exceed set limits for calories, saturated fat, sugar, and sodium content are required to carry highly visible front-of-package warning labels and are prohibited from marketing to children under 14 years of age.(76) Advertising is prohibited during broadcast programs or on websites either targeting children or with >20% child audience, and promotion and sales of these products is not allowed in schools.

Total Advertising ban (implementation July 2019),(77) that will restrict any advertising of the above products between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. on television or cinema. This follows the earlier child TV-focused marketing ban and captures the shifts from marketing focused on children’s TV with high-in foods to other TV programming(78).

Early evidence from Chile: In the first year post-implementation: The percentage of breakfast cereal packages using child-directed strategies dropped significantly from 36% to 21%, with a greater decrease among less healthy cereals that failed to meet the regulatory nutrition criteria (43% before implementation vs. 15% after).(79) The percentage of TV ads promoting unhealthy foods and drinks (i.e., products that failed to meet the policies’ nutrition criteria) decreased significantly from 42% pre-regulation to 15% post-regulation. In addition, the percentage of ads for unhealthy products that used child-directed appeals dropped significantly from 44% to 12%.(80) Preschoolers’ and adolescents’ exposure to TV advertising for junk foods decreased significantly by an average of 44 and 58%, respectively. Their exposure to junk food advertising that featured child-directed appeals (e.g., cartoon characters) also dropped by 35% and 52%, respectively.(81) While child exposure to ads with high amounts of added sugar, sodium and saturated fat decline, total ads did not change. Ads were shifted from children’s TV to other TV shows.(78) Marketing restrictions, in conjunction with other Chilean health regulations (the sugary drink tax and front-of-package warning labels), appear to have contributed to a roughly 24% drop in sugary drink purchases in the year following implementation.(82) Researchers have found large reductions in the sugar and sodium content of foods that did not meet the law’s nutrition criteria, suggesting that companies are reformulating products to contain lower amounts of nutrients of concer and thus avoid carrying warning labels or restricted marketing(83).

Keys to Effective Food Marketing Regulation: Effective regulations should address the types of foods and beverages regulated, the channels or platforms through which they are marketed (e.g., television, digital media, schools, sponsorships, etc.), and the audiences reached. Key concepts for developing effective regulations include the following: Partial measures are ineffective. Industry will find ways to avoid restrictions and has the resources to achieve the same reach to consumers through alternative channels.(84,85)

Conclusion – Implications for Policy

As seen with tobacco regulations, evidence indicates that 1) partial measures are ineffective and easy for industry to work around; 2) industry self-regulation does not work; and 3) rigorous regulations with real enforcement and consequences are necessary to reduce children’s exposure to harmful food and beverage marketing. More and stronger statutory policies are needed with wide coverage across all marketing channels and clear nutritional standards.(85-87) Policymakers should consider: Adopting strict, standardised nutrient profiling definitions to determine which products are unhealthy and thus should not be promoted to children (as in PAHO’s new Nutrient Profile Model,(88) or as implemented in Chile(89) and the United Kingdom90);(4,22,84,91) Prohibiting use of health and nutrient claims on products deemed too unhealthy to market to children.(92-94) Using more inclusive definitions of “child audience” (i.e., increasing age cut-offs and/or reducing child audience percentage cut points for advertising restrictions) and expanding TV restrictions beyond narrow windows of “children’s viewing hours”;(22,84,91,95,96) Expanding restrictions to better cover non-traditional media such as social media, online advergames, and more indirect and stealth marketing tactics that target children;(4,20,22,84,97) Cooperating between countries to minimise the impact of cross-border marketing;(4,98) and Establishing independent regulatory bodies to monitor and hold non-compliant companies accountable.(4,22,84,91,99)

Better protecting children from harmful food and beverage marketing through strong, statutory action is a crucial and correct step towards reversing the trends of childhood obesity and securing the health of the next generations.

Click here to view references.

Please note: This is a commercial profile