Searching in a dwarf galaxy, scientists have found a previously overlooked cache of massive black holes which may prove influential in future space research

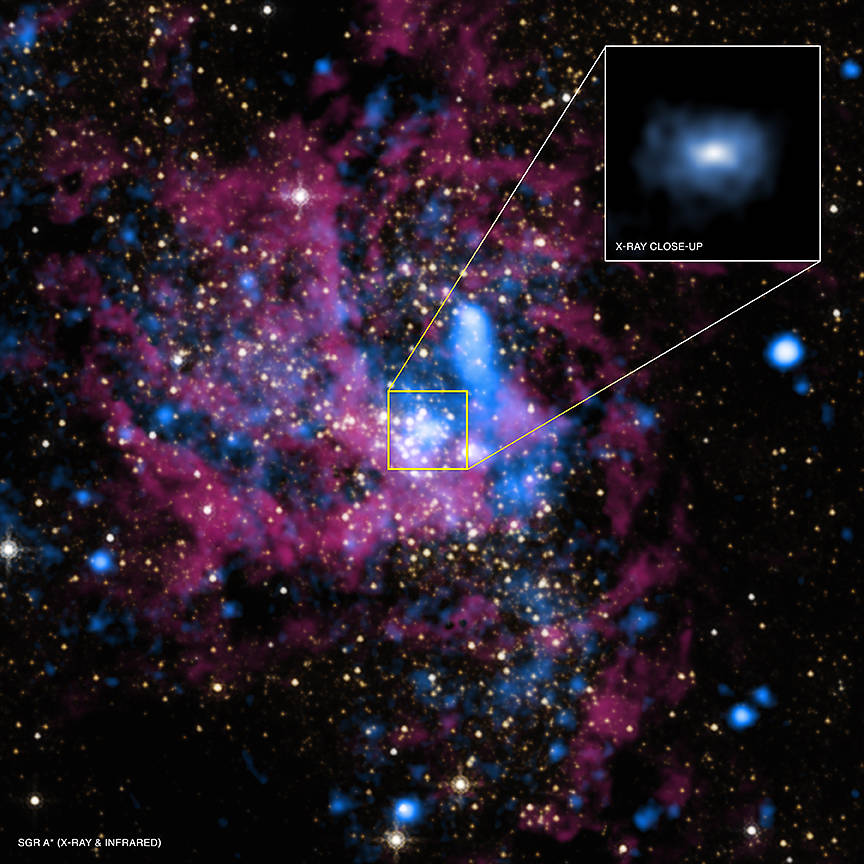

Researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill believe this new discovery will offer an into the life story of the supermassive black hole at the centre of our own Milky Way galaxy.

The ever-growing milky way is made of smaller dwarf galaxies

As a giant spiral galaxy, the Milky Way is believed to have been built up from mergers of many smaller dwarf galaxies.

Each dwarf that falls in may bring with it a central massive black hole. These massive black holes will have tens or hundreds of thousands of times the mass of our sun, and are potentially destined to be swallowed by the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole (Sagittarius A*).

How common are these massive black holes?

The quantity of these black holes however is unknown, we are still left in the dark when it comes to how many dwarf galaxies contain a massive black hole.

Published in the Astrophysical Journal the teams research attempts to fill this gap by revealing that massive black holes are many times more common in dwarf galaxies than previously thought.

black holes are many times more common in dwarf galaxies than previously thought

“This result really blew my mind because these black holes were previously hiding in plain sight,” said Mugdha Polimera, lead author of the study and a UNC-Chapel Hill Ph.D. student.

UNC-Chapel Hill Professor Sheila Kannappan, Polimera’s Ph.D. advisor and co-author of the study, compared black holes to fireflies. “Just like fireflies, we see black holes only when they’re lit up — when they’re growing — and the lit-up ones give us a clue to how many we can’t see.”

How can the team accurately detect black holes?

The path to discovery began when undergraduate students working with Kannappan tried to apply these tests to galaxy survey data. The team realised that some of the galaxies were sending mixed messages — two tests would indicate growing black holes, but a third would indicate only star formation.

“Previous work had just rejected ambiguous cases like these from statistical analysis, but I had a hunch they might be undiscovered black holes in dwarf galaxies,” Kannappan said.

She suspected that the third test was more sensitive than the other two to typical properties of dwarfs: their simple elemental composition (mainly primordial hydrogen and helium from the Big Bang) and their high rate of forming new stars.

Study coauthor Chris Richardson, confirmed with theoretical simulations that the mixed-message test results exactly matched what theory would predict for a primordial-composition, highly star-forming dwarf galaxy containing a growing massive black hole.

Polimera took on the challenge of constructing a new census of growing black holes, with attention to both traditional and mixed-message types. She obtained published measurements of visible light spectral features to test for black holes in thousands of galaxies found in two surveys led by Kannappan, RESOLVE and ECO.

A new type of growing black holes always show up in dwarfs

These surveys include ultraviolet and radio data ideal for studying star formation, and they have an unusual design.

“It was important to me that we didn’t bias our black hole search toward dwarf galaxies,” Polimera said. “But in looking at the whole census, I found that the new type of growing black holes almost always showed up in dwarfs. I was taken aback by the numbers when I first saw them.”

More than 80% of all growing black holes she found in dwarf galaxies belonged to the new type.

“We’re still pinching ourselves,” Kannappan said.

“We’re excited to pursue a zillion follow-up ideas. The black holes we’ve found are the basic building blocks of supermassive black holes like the one in our own Milky Way. There’s so much we want to learn about them.”