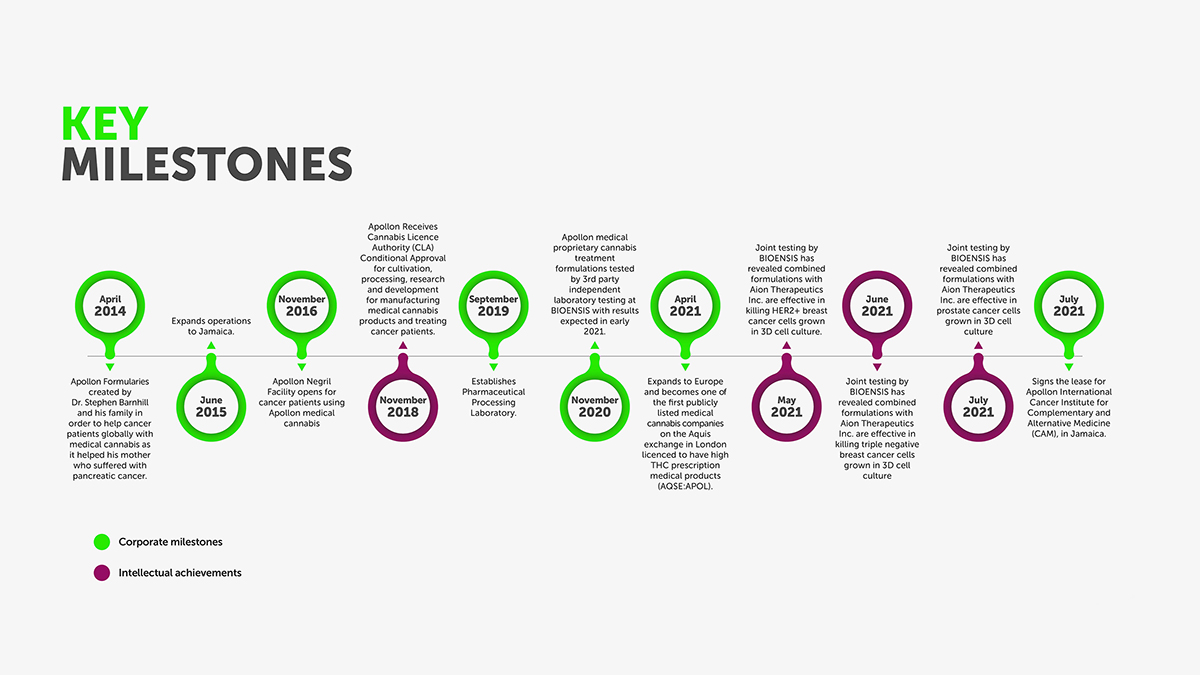

Dr Stephen Barnhill MD, CEO of Apollon Formularies Plc, examines medical cannabis and the future of cancer treatments across the UK and the European healthcare sectors

Early-stage research suggests that cannabis-derived medicines could be effective in treating various cancers. Recent experimental treatments and small-scale clinical trials have shown the importance of showing the efficacy of these medicinal cannabis formulations and will be a crucial and necessary path leading the way for medical cannabis to enter mainstream treatment for cancer patients.

For centuries, the plant Cannabis sativa L., has been used across the world as a herbal remedy. After ending its 50-year prohibition, medical cannabis was legalised in 2018 in the UK sparking renewed interest and research into the plant’s properties.

In cancer treatment, cannabinoids, the group of molecules, including CBD and THC, which constitute the active compounds in cannabis, have been primarily used as a part of palliative care to alleviate pain, relieve nausea and stimulate appetite. However, early-stage research and testing have suggested that medical cannabis may also be a highly effective treatment for killing cancer cells itself.

Several pre-clinical laboratory studies have shown that cannabinoids may reduce cancer cell growth and could disrupt the blood supply to cancerous cells, including brain tumours [1], breast cancers [2,3] and prostate cancer [4], among others.

As medicinal cannabis moves away from the ‘novel’ and into the mainstream, pharmaceutical companies will need to ensure that these medical formulations comply with current pharmaceutical gold standards with respect to consistent dosing, routes of administration, stability, clinical efficacy and safety. The new medicines will need rigorous protected intellectual property via defendable international patents, with actual clinical efficacy in patient data.

So how does it work?

Understanding how cannabis can treat cancer depends on the cannabinoids and the type of cancer in question, thus complicating the matter.

Results have shown that different cannabinoids can cause cell death (apoptosis), block cell growth through various inhibitors, stop the development of blood vessels (mTOR inhibitors) which are needed for tumours to grow, reduce inflammation through induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cell proliferation, suppression of cytokine production and induction of T-regulatory cells [5], and reduce the ability of cancers to spread (cell migration and metastasis).

With over 100 naturally occurring cannabinoids, there is no ‘one size fits all’ for medical cannabis in cancer treatment. Cutting edge work using artificial intelligence (AI) is being carried out to analyse cannabis plant genetics and phenotypes, to determine the best combination of cannabinoids, terpenes and flavonoids to target and optimise the treatment of various cancers.

Ongoing research: 3D cell cultures to clinical trials

Numerous scientific papers looking at cannabinoids and cancer have been published to date. However, due to years of prohibition, cannabis and its role in oncology currently lack the robust scientific evidence gained through extensive clinical trials.

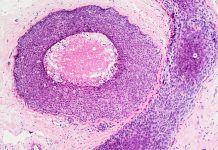

Before authorising human trials, potential cancer treatments can be tested through 2D or 3D cell culture testing. 3D cell culture models allow researchers to recreate specific pathophysiological environments and tumorigenic processes to identify potential biomarkers for therapeutic targeting or assessing cell response to therapies and drug efficacy.

The improvement in 3D cell culture technology has led to the generation of in vitro models that can encompass more physiological and tissue-specific microenvironments, with the aim to overcome the drawbacks observed in other pre-clinical models and have better predictive value for clinical outcomes.[6]

Despite the advancements in pre-clinical testing, the key to gaining cannabis’ full acceptance in the scientific community is real human data from clinical trials.

In the UK, researchers at the University of Birmingham are looking at the efficacy of Sativex – commonly associated with the treatment of Multiple Sclerosis – in treating Glioblastomas, the most common and most aggressive form of brain cancer. The second phase of human testing will assess whether adding Sativex to chemotherapy could extend the life of those diagnosed with Glioblastoma, which sadly has an average survival of less than 10 months [7].

Over in Europe, the University Medical Centre Groningen, in the Netherlands, is in phase II of testing the effect of cannabis oil on 20 liver cancer patients who have exhausted all other treatment options [8]. The trial, which launched in 2021, will run for three years and uses Transvamix® which contains 10% THC and 5% CBD [9].

These small scale clinical trials need to be licenced and expedited globally. Knowledge sharing in the scientific community will help remediate the years of lost research through prohibition.

The next steps: Personalised medicine

As our understanding of medical cannabis and its potential in oncology continues to grow, scientists are assessing the role of ‘personalised medicines’. As mentioned, with over 100 naturally occurring cannabinoids and many different types of cancer, there is no “one size fits all” for treatment.

Personalised medicine recognises that we are all physiologically unique and uses individual DNA sequencing to target treatment according to human microbiomes. As all cancers have a genetic base, personalised medicine is already commonly used in the traditional treatment of cancer. When combined with the powers of AI, personalised medicine presents a huge opportunity for medical cannabis and the treatment of cancer. It is estimated that one in two of us will get cancer within our lifetime [10] and in 2019, cancer caused more than one in four of all deaths in the UK [11]. By researching new alternative treatments, such as medical cannabis, we stand a real chance at improving survival rates and extending lives.

References

(1) Rocha, F. C. M., dos Santos Júnior, J. G., Stefano, S. C., & Da Silveira, D. X. (2014). Systematic review of the literature on clinical and experimental trials on the antitumor effects of cannabinoids in gliomas. Journal of neuro-oncology, 116 (1), 11-24.

(2) Apollon Formularies plc, https://polaris.brighterir.com/public/apollon_formularies/news/rns/story/r726zjw, Accessed January 2022

(3) Apollon Formularies plc, https://polaris.brighterir.com/public/apollon_formularies/news/rns/story/xq749kw, Accessed January 2022

(4) Apollon Formularies plc, https://polaris.brighterir.com/public/apollon_formularies/news/rns/story/x8ql8jx, Accessed January 2022

(5) Nagarkatti P, Pandey R, Rieder SA, Hegde VL, Nagarkatti M. Cannabinoids as novel anti-inflammatory drugs. Future Med Chem. 2009;1(7):1333-1349. doi:10.4155/fmc.09.93

(6) Law, A. M., Grundy, T. J., Fang, G., Valdes-Mora, F., & Gallego-Ortega, D. (2021). Advancements in 3D Cell Culture Systems for Personalizing Anti-Cancer Therapies. Frontiers in Oncology, 11, 782766-782766.

(7) The University of Birmingham, https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/2021/08/cannabis-brain-tumour-clinical-trial.aspx, Accessed January 2022

(8) The University of Groningen, https://www.rug.nl/about-ug/latest-news/news/archief2021/nieuwsberichten/umcg-studies-cannabis-oil-for-liver-cancer-patients-with-no-further-treatment-options?lang=en, Accessed January 2022

(9) Bedrocan, https://bedrocan.com/umcg-starts-scientific-research-into-cannabis-oil-and-liver-cancer/, Accessed January 2022

(10) Ahmad, A. S., Ormiston-Smith, N., & Sasieni, P. D. (2015). Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. British journal of cancer, 112(5), 943-947.

(11) Cancer Research UK, https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/mortality/all-cancers-combined, Accessed January 2022

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.

I think it is the antidotal nature of the reports and the general lack of documentation that raises my suspicions on the credibility of the stories. Since being involved in this area over the past 8 years, we have been unable to substantiate a single case of cannabis curing or even substantially impact on the course of a cancer diagnosis. There have been many cases that sound promising, and we have wanted to do case reports on his individuals. However, as we dug into the stories and saw some documented evidence it never panned out. The most common outcomes were the cancer patients continue to do the standard of care treatment, together with cannabinoids, and their outcome was what one would expect. In these cases, the patient believed it was the cannabinoids and not the standard of care that was responsible for the improvement [even in the face of well-documented evidence that their conventional treatment was expected to give them the result they wanted]. The other situation we have seen has been patients who think they still have cancer after their standard of care treatment and that the cannabinoid therapy cured them of the remaining disease. However, in these cases, there was no evidence of disease following standard care treatment.

I am a fan of cannabinoids and think we are just scratching the surface of its medical benefits [i.e. it has only been approved for very few things so far], but stories that tout miracle-like cures muddy the water, create false hope and is consistently used against those who want to take an evidence-based approach, making researchers jobs more difficult, not easier.