Professor Pierre Ronco describes advances in our understanding of membranous nephropathy and the promise of precision medicine to treat the disease

A rare disease which affects the kidney, membranous nephropathy is the second-most common cause of nephrotic syndrome, which is characterised by massive protein loss in the urine. The consequence of that is the decrease of serum albumin in the blood, generalised oedema, weight gain, fatigue, and sometimes fatal thrombotic complications such as lung emboli.

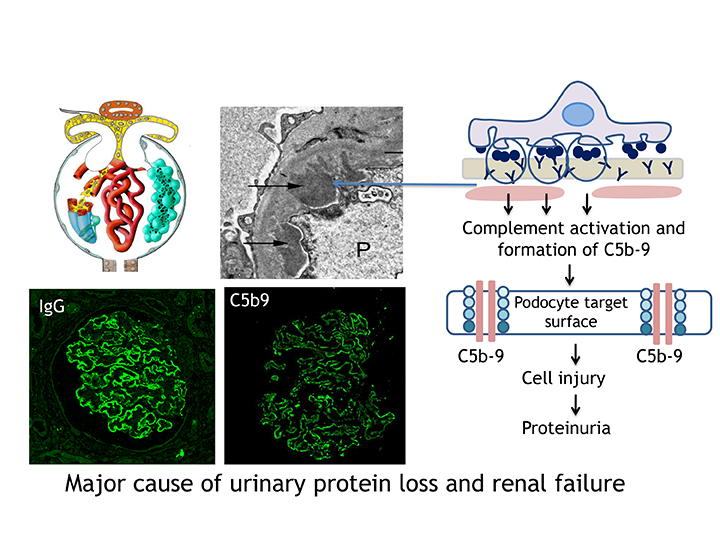

The disease can evolve in three ways; spontaneous remission, persistent proteinuria, or end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis or transplantation. It is caused by a thickening of the basement membrane of the glomerulus, a filtering unit in the kidney. This thickening is the consequence of the accumulation of immune deposits, composed of antibodies and antigens. The result of that is the activation of a cascade of inflammatory events which involves the complement system and causes proteinuria. Since the identification in the early 1980s of an antigen called megalin in Heymann’s nephritis, the rat model of the disease, the quest for a human antigen had been disappointing.

Moving towards more personalised medicine

My co-worker, Dr Hanna Debiec (Research Director at INSERM), and I re-opened the field in 2002 by characterising the first human antigen called neutral endopeptidase at the surface of podocytes, the cells in the glomerulus which control the selectivity of the renal barrier to proteins.

Interestingly, this antigen was identified in a rare subset of the disease that develops in neonates born to mothers that lack neutral endopeptidase and develop antibodies to it during pregnancy. This discovery provided the proof of principle that in humans like in the rat, a podocyte antigen could serve as target for pathogenic circulating antibodies.

Additional podocyte antigens have been identified including in 2009, the type-1 phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R1) and in 2014, the thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A (THSD7A), which are respectively associated with about 80% and more than 5% of adult forms of the disease. This clearly establishes that this disease is auto-immune in nature. My lab has also identified food antigens such as bovine serum albumin as a cause of the disease in young children. Other environmental factors may account for the dramatic increase in frequency of the disease.

These discoveries have been paradigm-shifting in patients’ care. They led to the development of diagnostic tests showing that the detection of anti-PLA2R antibodies in the blood was specific for the disease which means that a kidney biopsy, a potentially hazardous diagnostic procedure, is no longer needed. While measuring daily urinary protein excretion was the only means to evaluate disease activity, it has now been shown that high PLA2R1 antibody titres are associated with a worse prognosis and that antibody titre is correlated to disease activity.

A further step has been taken toward more personalised medicine with the identification of epitopes that are defined by small domains of the PLA2R1 antigen recognised by circulating antibodies. It has been shown that the more epitopes are recognised, the more severe the disease. Immune response spreading to additional epitopes will likely be accessible to routine lab tests in the near feature, which will allow most accurate evaluation of disease activity and risk for developing severe renal failure.

Triggering events behind membranous nephropathy

A lot of questions remain unsolved. One primary objective of my lab is to understand the triggering events that lead to the disease and the predisposing factors behind positive or negative outcomes. The first step is the presentation of the antigens to the immune system by the HLA class-2 molecules, which we have identified in our European consortium in a whole-genome study of more than 600 patients. What is not known is the trigger event: molecular mimicry with microbes or toxic agents could play an important role.

Neither does one know why the disease does not invariably progress to a point where treatment is required. Spontaneous remission could be due to the disappearance of the triggering event, or possibly another mechanism is involved. We think that genetic variants and epigenetic events within the HLA-D and PLA2R1 loci, and outside in the genome, might play an important role.

The current methods of treating membranous nephropathy rely primarily on immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids. Alongside their toxicity, there are two main problems with this method of treatment. The first is that a maximum of 70-80% of patients will enter remission of proteinuria. The second is that the effect of the treatment is delayed. It is necessary to develop alternative new therapies that will work more rapidly.

Implications for organ-specific autoimmune disease

Our OSAI project, supported by an advanced grant from the European Commission, is meant to address those questions. It is using cutting-edge techniques such HLA peptidomics – a method which has been developed with our colleagues in Zürich (Tim Fugmann, Dario Neri) – to identify PLA2R1 T-cell epitopes in the blood. This technique has never previously been used to study auto-immune disorders. The second key technique is molecular modelling of the membrane attack complex of complement.

With this model, we will be able to identify each of the possible intermediate steps of the membrane attack complex assembly. Then we can potentially propose new compounds that block complement assembly and prevent inflammation (collaboration with Bogdan Iorga, Paris).

This research could also hold implications beyond membranous nephropathy, as the condition is considered to be a paradigm of organ-specific autoimmune disease. A major objective is to propose predictive biomarkers to clinicians, in order to determine those patients who will need treatment and those who won’t, and this question is common to all organ-specific autoimmune diseases.

Professor of Nephrology

INSERM Institute and Sorbonne University in Paris Tenon Hospital (AP-HP)

Tel: +33 6 64 93 26 49

Please note: this is a commercial profile