An ongoing clinical trial led by the NCI Centre for Cancer Research reveals an experimental form of immunotherapy for metastatic breast cancer

According to this study, many people with metastatic breast cancer can mount an immune reaction against their tumours, a prerequisite for this type of immunotherapy, which relies on what are called tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Through a new clinical trial, researchers are hoping to use a patients own tumour-fighting immune cells to treat people with metastatic breast cancer.

Metastatic breast cancer (also called stage IV) is breast cancer that has spread to another part of the body, most commonly the liver, brain, bones, or lungs.

42 women with metastatic breast cancer were chosen for a clinical trail, 28 of those chosen (67%) generated an immune reaction against their cancer. The six clinically eligible patients from this trial were then ‘enrolled into one cohort of an ongoing phase II pilot trial of adoptive cell transfer.

“We’re using a patient’s own lymphocytes as a drug to treat the cancer by targeting the unique mutations in that cancer,” he said. “This is a highly personalised treatment” said study leader Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., chief of the Surgery Branch in NCI’s Centre for Cancer Research.

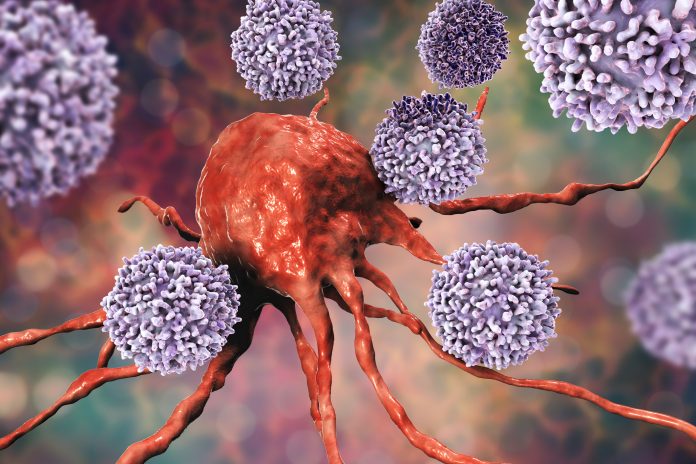

Immunotherapy relies on T cells

Immunotherapy is a treatment that helps a person’s own immune system fight cancer. However, most available immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, have shown limited effectiveness against hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, which are the majority of breast cancers.

The immunotherapy approach used in the trial was pioneered in the late 1980s by Dr. Rosenberg and his colleagues at NCI. It relies on TILs, T cells that are found in and around the tumour.

TILs can target tumour cells that have specific proteins on their surface, called neoantigens, that the immune cells recognise. Neoantigens are produced when mutations occur in tumour DNA. Other forms of immunotherapy have been found to be effective in treating cancers, such as melanoma, that have many mutations, and therefore many neoantigens.

Its effectiveness in cancers that have fewer neoantigens, such as breast cancer, however, has been less clear.

Was the treatment effective?

The approach was used to treat six women, half of whom experienced measurable tumor shrinkage. Results from the trial appeared Feb. 1, 2022, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“It’s popular dogma that hormone receptor–positive breast cancers are not capable of provoking an immune response and are not susceptible to immunotherapy,” said Dr Rosenberg.

“The findings suggest that this form of immunotherapy can be used to treat some people with metastatic breast cancer who have exhausted all other treatment options.”

For the six women treated, the researchers took the reactive TILs and grew them to large numbers in the lab. They then returned the immune cells to each patient via intravenous infusion. All the patients were also given four doses of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) before the infusion to prevent the newly introduced T cells from becoming inactivated.

After the treatment, tumours shrank in three of the six women. Two women had tumour shrinkage of 52% and 69% after six months and 10 months, respectively. However, some disease returned and was surgically removed. Those women now have no evidence of cancer approximately five years and 3.5 years, respectively, after their TIL treatment.

“It’s fascinating that the Achilles’ heel of these cancers can potentially be the very gene mutations that caused the cancer,” said Dr. Rosenberg.

“Since that 2018 study, we now have information on 42 patients, showing that the majority give rise to immune reactions.”