The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics found that growing interest in moon resources could create international tension, as extraction becomes possible

The concept of colonising space is something that has been dreamt and feared across the world for decades. The race to access space resources, send out satellites, astronauts, and conduct highly-impactful research has long defined how powerful a country is. In March, 2019, Prime Minister Modi launched ‘Mission Shakti’, to establish India as the fourth space power country.

Space power is a relatively new, nebulous idea.

But it has to align with the needs and wants of the Earth-dwelling population, especially nation to nation. In every country, there is an increasing need for natural resources, and global status. The recent news of water availability on the moon adds to the knowledge that Helium-3 (a rare element that could help develop the energy sector) and Rare Earth Metals (REM) are already on the moon. Right now, China produces 90% of the world’s REM – which are essential to making electronics. The first country to extract resources from the moon will be firmly established as a crucial space power, potentially altering who controls REM.

‘There’s no law’

“A lot of people think of space as a place of peace and harmony between nations. The problem is there’s no law to regulate who gets to use the resources, and there are a significant number of space agencies and others in the private sector that aim to land on the moon within the next five years,” said Martin Elvis, astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian and the lead author on the paper.

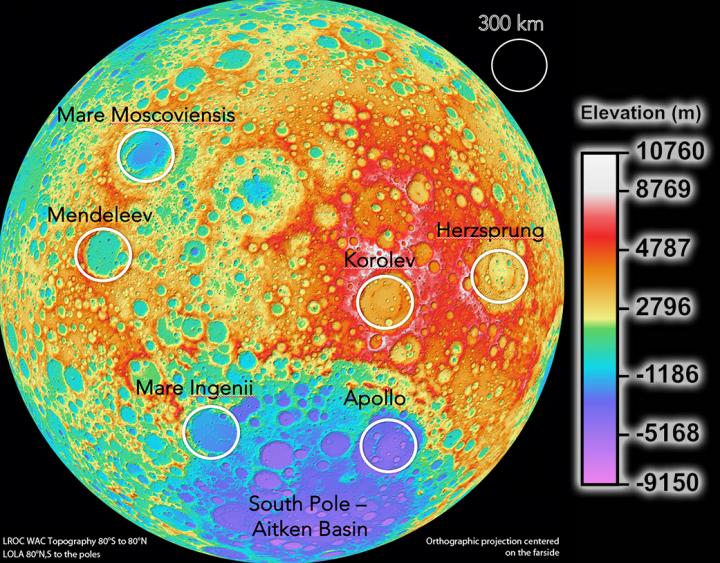

“We looked at all the maps of the Moon we could find and found that not very many places had resources of interest, and those that did were very small. That creates a lot of room for conflict over certain resources.”

Resources like water and iron are important because they will enable future research to be conducted on, and launched from, the moon. “You don’t want to bring resources for mission support from Earth, you’d much rather get them from the Moon. Iron is important if you want to build anything on the moon; it would be absurdly expensive to transport iron to the moon,” said Elvis. “You need water to survive; you need it to grow food–you don’t bring your salad with you from Earth–and to split into oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel.”

What are the existing laws for space?

Some treaties do exist, like the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which bans national appropriation, and the 2020 Artemis Accords, which confirm the duty of any country to coordinate and notify on space missions. However, neither are strong enough to really protect any part of space. The moon is now being looked at in terms of commercial versus scientific activity – including who should be allowed to access the moon resources.

What could countries do to make this work?

Alanna Krolikowski, assistant professor of science and technology policy at Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) and a co-author on the paper, added that a framework for success already exists: “While a comprehensive international legal regime to manage space resources remains a distant prospect, important conceptual foundations already exist and we can start implementing, or at least deliberating, concrete, local measures to address anticipated problems at specific sites today.

“The likely first step will be convening a community of prospective users, made up of those who will be active at a given site within the next decade or so. Their first order of business should be identifying worst-case outcomes, the most pernicious forms of crowding and interference, that they seek to avoid at each site. Loss aversion tends to motivate actors.”

Is there really that much on the moon?

There is still a risk that resource locations will turn out to be more scant than currently believed, and scientists want to go back and get a clearer picture of resource availability before anyone starts digging, drilling, or collecting.

“We need to go back and map resource hot spots in better resolution. Right now, we only have a few miles at best. If the resources are all contained in a smaller area, the problem will only get worse,” said Martin Elvis.

“If we can map the smallest spaces, that will inform policymaking, allow for info-sharing and help everyone to play nice together so we can avoid conflict.”