A sufficient freshwater supply is essential to ecosystems, societies, and economies. Given the continuous increase in global population, improved living standards and rampant economic growth, there is an ever-growing worry about water scarcity

The increasing global food demand can often only be met through massive increases in irrigation activities (e.g., Kummu et al., 2016). Additionally, if various sectors compete for limited water resources, mounting water scarcity is often addressed at the expense of environmental water needs. That leads to the degradation of aquatic ecosystems, biodiversity loss (Arthington et al., 2010; Pastor et al., 2014; Tickner et al., 2020), and depletion of groundwater resources (e.g., Bierkens and Wada, 2019).

The unequal distribution of scarce water resources can also give rise to legal and institutional conflicts at local to international levels. (e.g., Veldkamp et al., 2017).

Water scarcity – A multi-dimensional problem

Maintaining a sufficient fresh water supply is not just threatened by the overexploitation of water resources. Anticipated climate change alters regional hydroclimatological conditions and affects the occurrence and intensity of extreme events (e.g., droughts).

Water scarcity will rise globally, and even countries with abundant water resources may face water shortages in the future due to the increasing imbalance between growing demand and changing supply (Greve et al., 2018). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG6 “Clean Water and Sanitation”, established by the United Nations in 2015, recognize the significance of tackling this global issue.

Water security and environmental sustainability will only be achieved by massively reducing unsustainable water use now and continuously within the following decades.

GERICS urges to fill existing research gaps

The multi-dimensional and systemic nature of water scarcity and the associated high societal impacts require the entire portfolio of GERICS expertise. A newly formed junior research group focusing on uncertain global water resources under global change will tackle the problem from multiple angles.

Current earth system models offer a physical representation of processes and interactions between different components of the climate system, but they do not represent specific and more practical end-user needs. The emerging development and use of socio-hydrological models can provide a broader perspective and more detailed insights. However, these models do not account for the climate feedback from large-scale water management practices such as irrigation and reservoirs.

GERICS researchers (Asmus et al., 2021) have, for example, recently demonstrated how extensive irrigation can alter the local water and energy balance, leading to potential effects on daily temperatures and afternoon rainfall.

Processes related to water management practices are not yet routinely considered in the newest generation of climate models. GERICS aims to close that research gap by incorporating water management practices into its in-house climate model REMO. This will be done by building on the knowledge and expertise of the socio-hydrological community.

Adaptation options tackling water scarcity

Adapting to climate change and enhancing land and water resources management is imperative to achieve a sustainable freshwater supply, particularly in regions where water is scarce. However, water managers and stakeholders often face insufficient and inaccessible data and models, high uncertainties, and vague scenarios. Therefore, sustainable, practical, and achievable adaptation options and associated climate services must be designed collaboratively.

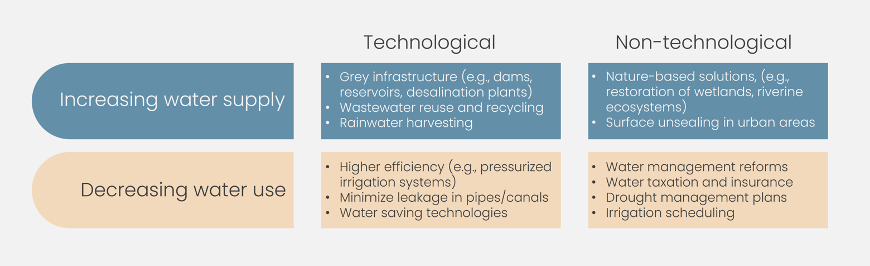

Including all actors in that process and considering their needs, visions, and desired futures is essential. GERICS has extensive experience in working with end-users and can contribute to designing and evaluating much-needed sustainable water adaption pathways within urban, regional, and multi-national contexts. To reduce water scarcity, there are two main approaches: increasing water supply and decreasing water demand. These approaches can be implemented through technological or non-technological adaptation measures (see Fig. 1).

While grey infrastructure is effective, it is expensive to build and maintain and can harm aquatic ecosystems. Nature-based solutions are often equally efficient, promote ecosystem functioning, and provide additional benefits such as flood protection. In addition, hybrid approaches, such as artificial groundwater recharge or porous pavements, can locally increase water availability.

Non-technological interventions, such as water taxation, insurance schemes, or tariffs on virtual water trade, can also help reduce water use and may foster the fair share of limited water resources among different users. In addition to political and economic interventions, raising awareness about the limited availability of water is crucial, particularly in regions that have historically had abundant water resources but may face water shortages in the future.

Choosing a well-composed set of appropriate adaptation techniques that are both sustainable and effective requires a holistic approach based on localized assessments, the involvement of all relevant actors, and the consideration of environmental water needs. The team at GERICS has extensive expertise that can support the entire process, including addressing potential adverse side effects that, for example, may impact human health.

The measures taken must also be fair, just, and inclusive of marginalized groups and specific ecosystem requirements. Therefore, successfully implementing sustainable water adaptation options also requires robust institutional and legal infrastructures and functioning water governance. However, that is challenged by existing socio-political barriers and conflicting economic interests, increasing the demand for effective climate services.

References:

- Arthington, A. H., Naiman, R. J., McClain, M. E. & Nilsson, C. Preserving the biodiversity and ecological services of rivers: new challenges and research opportunities. Freshwater Biology 55, 1–16 (2010).

- Asmus, C., Hoffmann, P., Pietikäinen, J.-P., Böhner, J., and Rechid, D.: Modeling irrigation effects on the regional climate in the “Greater Alpine Region” using a newly developed parameterization, EMS Annual Meeting 2021, online, 6–10 Sep 2021, EMS2021-176

- Bierkens, M. F. P. and Wada, Y. Non-renewable groundwater use and groundwater depletion: a review. Environmental Research Letters, 14(6), 063002 (2019)

- Greve, P. et al. Global assessment of water challenges under uncertainty in water scarcity projections. Nature Sustainability, 1, 486-494 (2018)

- Kummu, M. et al. The world’s road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Scientific Reports, 6, srep38495. (2016)

- Pastor, A. V., Ludwig, F., Biemans, H., Hoff, H. & Kabat, P. Accounting for environmental flow requirements in global water assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 5041–5059 (2014)

- Tickner, D. et al. Bending the Curve of Global Freshwater Biodiversity Loss: An Emergency Recovery Plan. BioScience, 70(4), 330–342 (2020)

- Veldkamp, T. I. E. et al. Water scarcity hotspots travel downstream due to human interventions in the 20th and 21st century. Nature Communications 8, ncomms15697 (2017).