Reaching the net zero targets announced by countries around the world isn’t just about generating cleaner energy: it will also require significant improvements in making our energy use more efficient

Energy efficiency can contribute up to 40% of the emissions reductions required to meet the 2050 net zero targets, but a “business as usual” approach will do little to achieve change on the scale required.

Tech and the energy sector

The energy sector is responsible for three quarters of global emissions and achieving significant energy efficiency improvements within this sector will be the difference between achieving, or falling well short, of the 2050 net zero targets.

Digital technologies are transforming the energy sector and creating a new generation of energy efficient solutions. New digital solutions can limit production and distribution losses and accommodate growing shares of variable and distributed renewable energy while increasing grid flexibility. In recent years, energy management systems in buildings have also become smarter, integrating external data sources, like weather conditions, traffic patterns, and more. Using artificial intelligence, these advanced systems can forecast energy demand and improve response capabilities.

The potential benefits of capitalising on these existing digital solutions are significant. IEA analysis estimates that through using the technology already available, we could improve the efficiency of more than 12% of 2018 global electricity consumption. By 2050 that improvement potential will nearly double, representing about one-quarter of global electricity consumption.

The role of Governments?

Governments can play a key role in scaling the market for these smart devices through standards, regulations, incentives or information sharing. Digitalisation will play a key role in rapidly growing cities where dense populations, increasingly high concentrations of electric vehicles, and innovative district energy, heating, and cooling systems can work in sync to optimise demand and consumption, improving efficiency and reducing emissions.

However, some of the proposed solutions seem well beyond the realms of possibility as they would require buildings all around the world to improve their energy intensity by up to 50%, and as of June 2020, we were already well behind the required rate of progress.

This solution, which is described as a core component of net zero target, is being presented as the “logical” or “common sense” approach. However, reality is the polar opposite because the wholesale changes required to building regulations and thereafter enforcement measures, would already need to be in place in order to deliver the improvements within the net zero target timeframe.

For a moment let us set aside the length of time wholesale regulatory changes would take to draft, pass into law and implement, given they have to go through a notoriously slow bureaucratic process, even if everyone was in agreement. Let us also set aside that retrofitting existing building stock on a global scale, as laid out in this plan, would take decades and cost trillions. The fact remains some of the very same organisations politicians rely on for support and funding are the same organisations that prioritise economic stability, economic growth and economic opportunities, which a solution such as this would undermine on a fundamental level, especially when we consider we are also faced with a huge economic recovery challenge due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This puts a serious dent in the net zero agenda especially when we also factor in that the wind energy contribution to the net zero target is also reliant on some very optimistic and clearly unrealistic targets, as covered in a previous article.

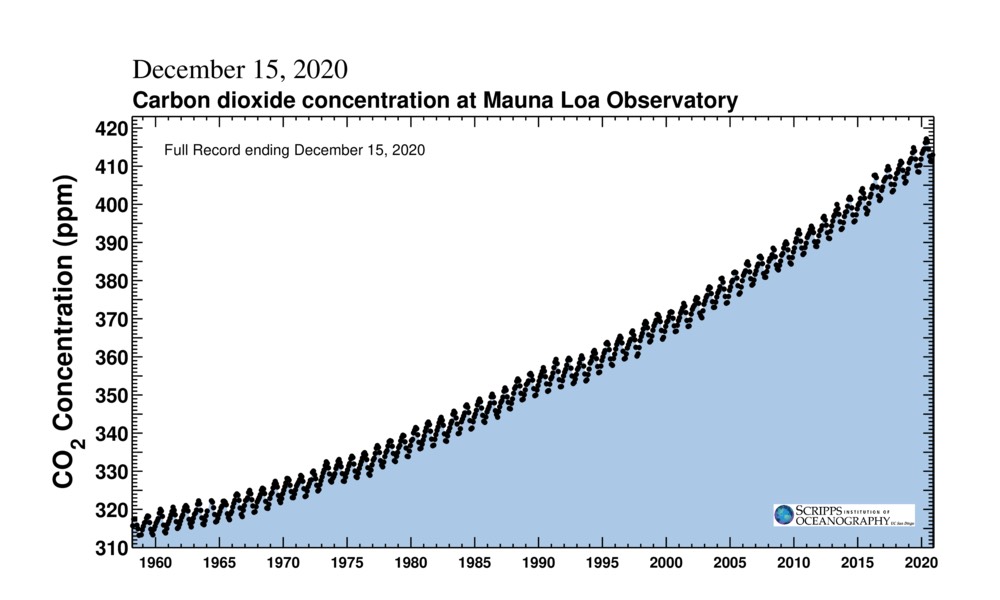

We have also covered in a previous article the chasm between net zero policy and goals, in which we identified a 30 year downward trend in emissions, achieved mainly through private sector competition to increase turnover and market share, rather than policy. It should also be noted that in the same 30 year period, whilst emissions have been reducing and the international community has been entering into climate pacts and accords, the levels of atmospheric CO2 has continued to rise at a consistent rate.

It should be further noted that during the numerous global COVID-19 lockdowns, fossil fuel use has massively decreased, but for some reason this has not translated into a reduction of atmospheric CO2, which brings in to question the widely held belief that increased fossil fuel use and human activity are the main cause of both increasing levels of CO2 and global warming.

Nearly 200 countries to act

According to the World Economic Forum, under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nearly 200 countries said they would act to limit the rise in global average temperatures to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times and strive to keep it to a ceiling of 1.5C. But the world has already heated up by about 1.1C and is currently on track for warming of at least 3C this century as emissions continue to rise. Scientists say that would bring ever-worsening extreme weather and potentially catastrophic sea level rise, making some parts of the planet uninhabitable and fuelling hunger and migration.

That – and mounting public pressure – is why a growing number of countries, companies and others are promising to cut their planet-warming emissions to net zero by 2050 or before.

However, based on the observable evidence over the last three decades, it would seem there is another factor at play, which has yet to be considered or factored in.