The new “plug-and-play” biobattery developed by researchers at Binghamton University State University of New York has proven its worth – with the team revealing it can last for weeks at a time

With the Internet of Things continually increasing the connectivity of our devices and sensors together, providing power to remote locations has become an increasingly important and expanding field of research.

Professor Seokheun “Sean” Choi, faculty member in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, has been working towards creating a bacterial interaction-fuelled biobattery for a number of years.

The inherent problem with biobatteries

Up until now, a key problem with Choi’s research had been the lifespan of the biobattery. Previously the batteries had a lifespan limited to a few hours – not ideal for the long-term scenarios he was aiming for.

Long-term monitoring in remote locations will require an extended battery life, however, is this really possible?

Published in the Journal of Power Sources and supported by a $510,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research, Choi and his collaborators have developed a “plug-and-play” biobattery that lasts for weeks at a time and can be stacked to improve output voltage and current.

Choi’s previous batteries had two bacteria that interacted to generate the power needed, but this new creation uses three bacteria in separate vertical chambers: “A photosynthetic bacteria generates organic food that will be used as a nutrient for the other bacterial cells beneath. At the bottom is the electricity-producing bacteria, and the middle bacteria will generate some chemicals to improve the electron transfer.”

Connecting remote locations

The most challenging application for the Internet of Things, Choi believes, will be wireless sensor networks deployed unattended in remote and harsh environments.

These sensors will be far from an electric grid and difficult to reach to replace traditional batteries once they run down. Because those networks will allow every corner of the world to be connected, power autonomy is the most critical requirement.

“With artificial intelligence, we are going to have an enormous number of smart, standalone, always-on devices on extremely small platforms. How do you power these miniaturised devices? The most challenging applications will be the devices deployed in unattended environments. We cannot go there to replace the batteries, so we need miniaturised energy harvesters” said Choi.

‘Lego brick’ batteries

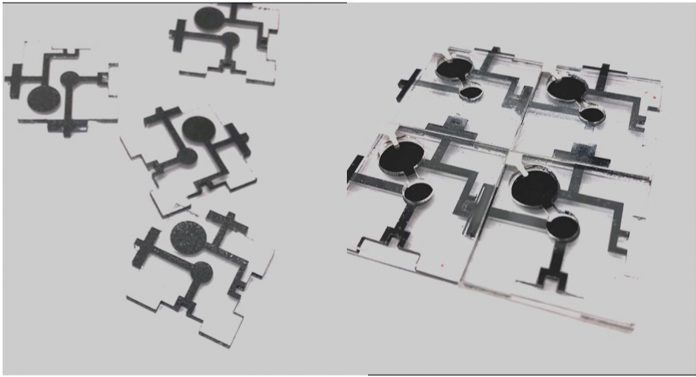

Measuring 3 centimetres by 3 centimetres square — Choi has compared these new biobatteries to Lego bricks that can be combined and reconfigured in a variety of ways depending on the electrical output that a sensor or device needs.

Among the improvements he hopes to achieve through further research is creating a package that can float on water and perform self-healing to automatically repair damage incurred in harsh environments.

“My ultimate target is to make it really small,” he said. “We call this ‘smart dust,’ and a couple of bacterial cells can generate power that will be enough to operate it. Then we can sprinkle it around where we need to.”