COVID-19 came from Wuhan, China, but the conditions that enabled the virus to jump from animal to human are not unique – so where could the next pandemic begin?

This dark but urgently asked question will bring fear and a sense of dread. Already, the escape through vaccination in Spring 2021 appears to be a distant horizon, with regulatory authorities and distribution ethics lining the way ahead. Populations across the world are longing to go back to their lives, with some suspended in a near-constant lockdown status since pandemic status was declared back in March.

Conspiracy theories pinned the existence of COVID-19 to the Chinese Government – a popular theory that even swayed President Donald Trump, who described the virus as an intentional action by China during his handling of the crisis. However, numerous scientific sources found that COVID-19 was originally a virus prevalent in bats and pangolins, which had made its way into a human body.

Throughout the world, humans eat animals. Animals continue to carry viral diseases. Research led by the University of Sydney and with academics spanning the United Kingdom, India and Ethiopia, examines the cities in the world which are most at risk of the next pandemic. Last month, an IPBES report highlighted the role biodiversity destruction plays in pandemics and provided recommendations.

Where are the most likely places for the next pandemic?

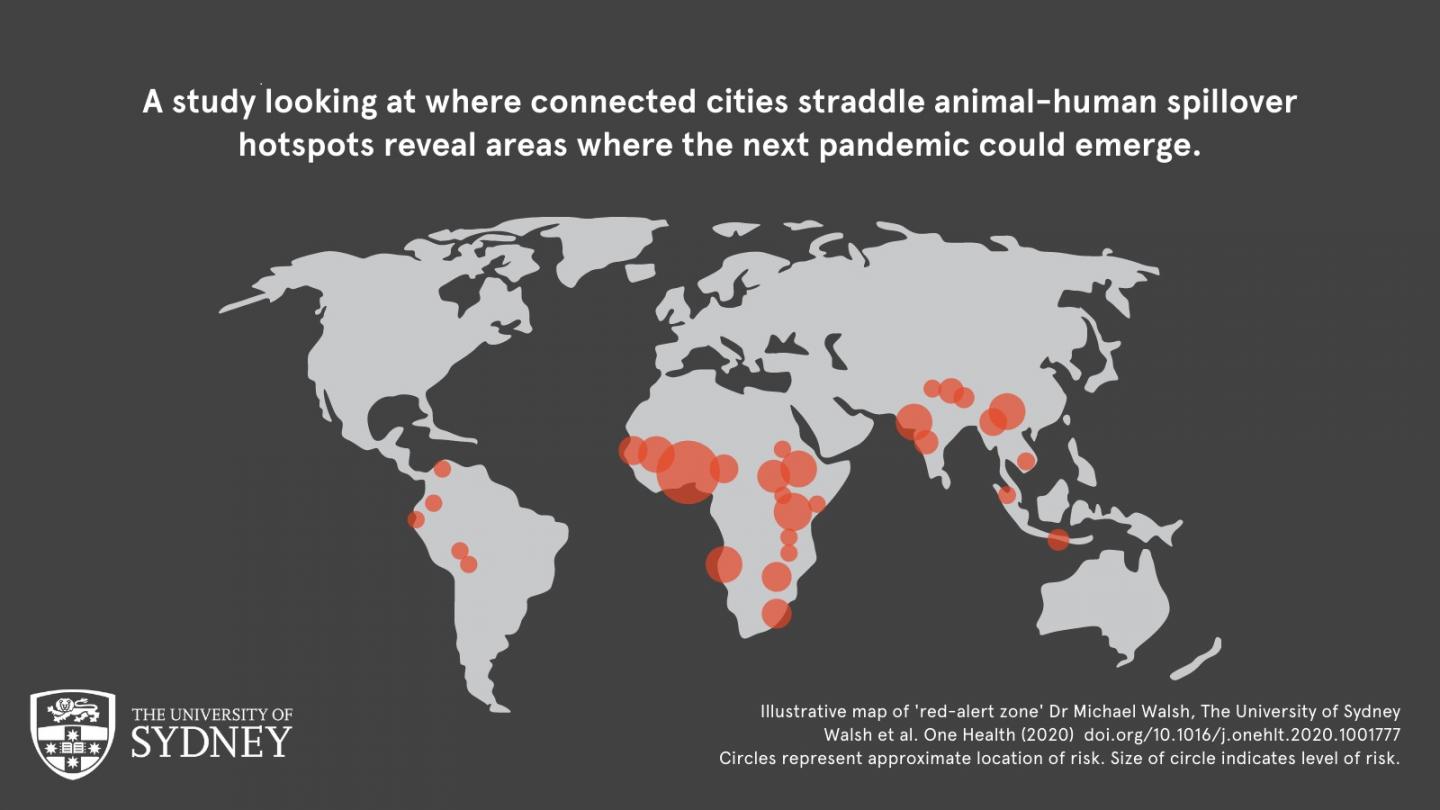

Areas exhibiting a high degree of human pressure on wildlife also had more than 40% of the world’s most connected cities in or adjacent to areas of likely spillover, and 14-20% of the world’s most connected cities at risk of such transference likely to go undetected because of poor health infrastructure (predominantly in South and South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa). As with COVID-19, the impact of diseases jumping from animal to human could be tragically global.

This is essentially half of the world’s cities.

Lead author Dr Michael Walsh, who co-leads the One Health Node at Sydney’s Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, said that previously, much has been done to identify human-animal-environmental hotspots.

“Our new research integrates the wildlife-human interface with human health systems and globalisation to show where spillovers might go unidentified and lead to dissemination worldwide and new pandemics.”

Habitat conservation could help to stop it

Of those cities that were in the top quartile of network centrality, approximately 43% were found to be within 50km of the spillover zones and therefore warrant attention (both yellow and orange alert zones). A lesser but still significant proportion of these cities were within 50km of the red alert zone at 14.2% (for spillover associated with mammal wildlife) and 19.6% (wild bird-associated spillover).

Dr Walsh said although it would be a big job to improve habitat conservation and health systems, as well as surveillance at airports as a last line of defence, the benefit in terms of safeguarding against debilitating pandemics would outweigh the costs.

He further commented: “Given the overwhelming risk absorbed by so many of the world’s communities and the concurrent high-risk exposure of so many of our most connected cities, this is something that requires our collective prompt attention.”