Experts have claimed that we may have to wait until the second half of the century for nuclear fusion energy

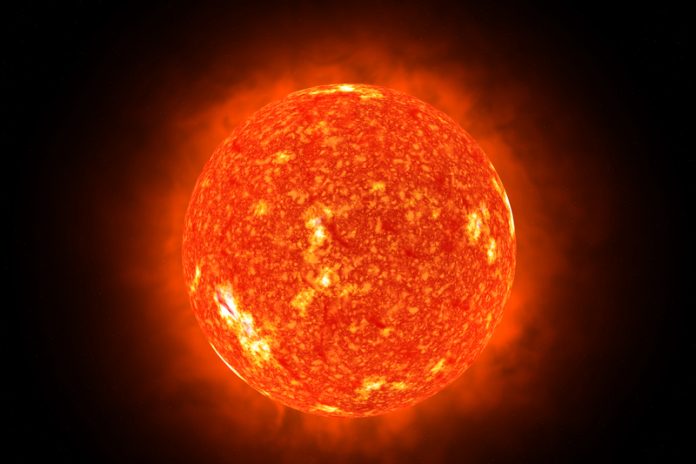

Nuclear fusion is a process of superheating the nuclei of light atoms such as hydrogen, causing them to join together and generate massive amounts of energy in the process.

Essentially, it uses the same reaction as the sun to generate energy and in theory can provide renewable, green, unlimited power.

The nuclear waste created in the process would also have a shorter half-life than waste generated from traditional nuclear energy.

However, experts have now claimed that we may have to wait until 2050 for the process to be perfected.

Setbacks have been caused by massive increases in cost, as well as complex political situations.

Reactor ITER, based in the south of France, is a collaboration between many different countries, with Europe paying the lion’s share of costs.

Many of these countries are also creating their own reactors, meaning that support is becoming divided.

The future

Not everyone is pessimistic about the potential of realising nuclear fusion in the foreseeable future.

For the first time ever scientists in Lawrence Livermore National Ignition Facility (NIF) have managed to recreate the extreme heat and plasma conditions found at the centre of stars 40 times as large as our own sun.

Physicist Dan Casey explained how this can lay the groundwork for nuclear fusion, saying:

“This really establishes a new tool in the nuclear astrophysics field for studying various processes and reactions that may be difficult to access any other way.

“Perhaps most importantly, this lays the groundwork for potential experimental tests of phenomena that can only be found in the extreme plasma conditions of stellar interiors.”

This, along with global powers including Google and the Chinese government all racing to be the first to produce fusion energy, could mean the possibility is not as far off as it may seem.

US Princeton physicist Robert Goldman has called it ‘a question of commitment of manpower’.

The main challenge now, it seems, is overcoming the cost of experimentation.