Ocean acidity is an essential variable in validating climate models, accurately predicting complex environmental dynamics and major changes to Pacific Ocean currents

Recent climate modelling and geochemical data research has confirmed changes to Pacific Ocean currents, including those that impact weather pattern events like El Niño, suggesting they may be more likely to occur with just a few degrees of global warming.

El Niño affects weather extremes, food security, economic productivity, and public safety for a large population of the planet. There is still much discussion as to how well El Niño dynamics are captured by climate models. However, to calculate climate events like El Niño, researchers began measuring ocean acidity rather than water temperature.

Looking beyond ocean temperature and circulation models

Yale climate scientists like Alexey Fedorov have been conducting research on ocean dynamics around the world over the last ten years, analysing events like El Niño, including the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, featuring abnormally warm water in the Pacific.

Fedorov developed climate model simulations that look at ocean temperature proxies of the distant past, when global temperatures were several degrees warmer, as well as the present, to predict what might happen in the future, when the world is probably going to be warmer.

The climate scientists aimed to look at whether ancient temperature data in their models and other climate models were accurately capturing the past climate state.

Lead author Madison Shankle, a former Yale researcher now at the University of St Andrews School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, said: “Accurately capturing ocean dynamics in the equatorial Pacific in global climate models is crucial for predicting regional climate in the warmer decades to come.”

Pincelli Hull, Assistant Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and principal investigator for the new study, said: “We decided to test model predictions of major changes to the winds and currents driving El Niño by measuring something else, rather than temperature. We measured ocean acidity instead.”

Ocean acidity, the amount of pH in the Earth’s oceans based primarily on the amount of carbon dioxide that oceans absorb from the atmosphere, was used as a measurement in this study. As carbon dioxide in the ocean increases, pH decreases.

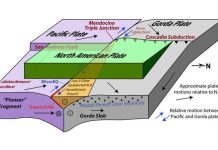

The team from the numerous participating universities thus used boron isotopes to infer ancient ocean acidity, focused on the equatorial Pacific during the Pliocene Epoch, 2.6 to 5.3 million years ago – the Pliocene being a warm period of Earth’s past that climate scientists often use as an analogue for today’s warming planet.

Three primary discoveries were made by the researchers

Firstly, when using geochemical proxies, the researchers found a much more acidic eastern equatorial Pacific during the Pliocene, compared to today.

Second, these acquired results matched climate model predictions from co-author Natalie Burls – a former Yale researcher – due to a water circulation system that acted like a conveyor belt, bringing up even deeper, older, and more acidic water.

Finally, the researchers found that the delivery of this older, acidic water required an ‘overturning circulation’, the ocean conveyor belt, that had previously been predicted by Burls and Fedorov.

This new information also suggests that ocean acidity can be a key measurement as climate models attempt to make projections for warmer conditions than those found today.

Shankle said: “Rather than being a few decades old as is found today, the upwelled water in the warm Pliocene travels thousands of miles from the North Pacific at depths of about 1000 metres before finally upwelling in the eastern equatorial Pacific, making the water in the order of hundreds of years old.”

Hull added: “It was this remarkable confirmation of Natalie and Alexey’s model. It means our current set of climate models are working pretty well. It gives us more confidence in the ability of models to predict large, regional changes in ocean and climate dynamics that really matter.”

Planavsky commented: “This is a powerful way to test models and ideas about how the climate system works that is beyond our current technological capacity to assess on the basis of past temperature proxy estimates alone.”