In 2018, the UK proposed stronger ‘online harms’ regulation, to address harmful content that children can see on social media – by asking tech giants to self-regulate or face Government investigation

In 2017, 14 year old Molly Russell took her own life. Her Instagram was directly connected to how she felt, containing a lot of media related to depression and suicide. Instagram commented at the time that it doesn’t allow anything that “glorifies self-harm or suicide,” but this can still be quickly disproved with a search on the platform – even in 2020.

The Facebook funding threat

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) fought a two year freedom of information battle to gain access to a conversation between Matt Hancock and Mark Zuckerberg. This conversation happened at a tech summit in Paris in 2018. Facebook CEO Zuckerberg threatened to pull funding from the “anti-tech UK government”, joking about not visiting the UK in the same way he doesn’t visit China.

According to records released by the BIJ, the meeting notes concluded: “If there really is a widespread perception in the valley that the UK Government is anti-tech then shifting the tone is vital. London Tech Week is a great opportunity, and couldn’t have arrived at a better time.”

This suggests that the UK Government was prepared to pivot on implementation of online content regulation, to keep Facebook’s ongoing investment into the country. Around the time of this meeting, Facebook employed 2,300 staff in the UK. A few months later, Zuckerberg signed a lease on a huge King’s Cross office space – which was a win in the aftermath of Brexit’s repelling effect on some international manufacturing companies.

If the online harms regulation proposal was as strong as initially proposed in early 2018, would Zuckerberg have continued to invest in office space, staff and digital news schemes in the UK?

Online self-harm communities

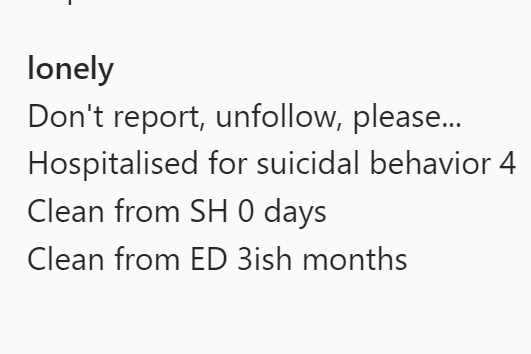

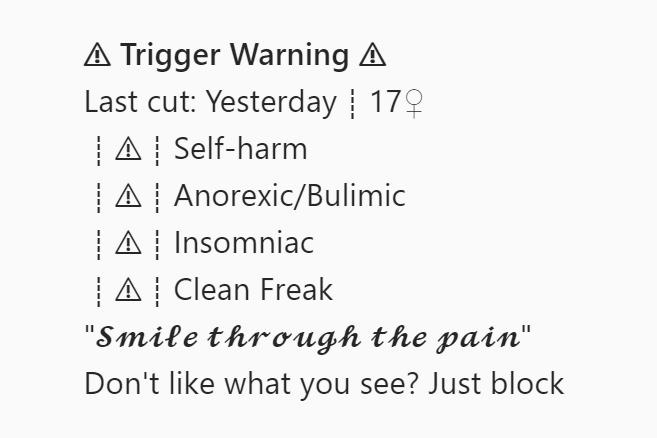

The glorification of eating disorders, self-harm, and suicidal ideation can be found on secretive but openly accessible pages which post psychologically harmful content.

While TikTok has firmly replaced Instagram as the go-to social media decision for young people, with its own host of issues – as a Chinese app, it remains far outside the boundaries of the UK’s capacity to enforce regulatory decisions. So right now, the focus is on platforms like Instagram.

These Instagram pages are curated with the knowledge that this content is harmful, with several asking the viewer not to expose their account to regulatory actions – even adding trigger warnings, to give everyone a quick heads-up. This kind of secret-keeping creates the feeling that this behaviour is normal and even inevitable, untreatable. Especially with the solidarity of being validated by similar accounts, who are run by similarly vulnerable people.

On one hand, individuals allegedly look out for one another. But on the other, dominant hand, individuals support the idea that they truly belong to this dark, digital community – rendering them not fully present to engage with medical support mechanisms in the physical world.

In 2020, children can access this kind of community on Instagram with little to no difficulty. In writing this, I have found at minimum 50 accounts that glorify self-harm and support eating disorders by providing unhealthily skinny images. Back in 2017, Molly’s father Ian said that he blamed Instagram for having partial responsibility in his daughter’s death, and the UK Government launched an online harms white paper in 2018 as a follow-up measure to the tragedy that permeated parent’s minds throughout the UK.

Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport in 2017, Matt Hancock, said: “We are moving forward with our plans for online platforms to have tailored protections in place – giving the UK public standards of internet safety unparalleled anywhere else in the world.”

Where is the online harms regulation in 2020?

On 8 October, Digital Minister Caroline Dinenage said legislation could be expected to be ready early next year, in 2021. This bill will go through parliament with the express knowledge that Facebook investments, crucial in the wake of Brexit, hinge on a largely toothless legislation that enables the big tech firms to self-regulate without serious intervention or sanctions. She further told MPs increases in the use of “revenge porn” are “unacceptable” and need to be addressed, while remaining vague on the date and impact of online harms regulations.

Speaking in the same debate, shadow digital minister Chi Onwurah said tech has huge potential for good, and that people should be “empowered” to use the digital tools available to them. She commented: “The internet is increasingly now a dark, challenging, and inhospitable place. Regulation has not kept pace with technology, crime, or consumers, leaving growing numbers of people increasingly exposed to significant online harm.”

Lord David Puttnam, Chair to the Committee on Democracy and Digital, commented: “Here’s a bill that the Government paraded as being very important but which they’ve managed to lose somehow.” He further suggested that the proposed timeline by current Digital secretary, Caroline Dineage, would mean that the legislation would be implemented in 2023 or 2024, “seven years from conception – in the technology world that’s two lifetimes.

“In a child’s world it is also about two lifetimes. And that is unacceptable.”