Alison White of PLACEmaking asks: Are organisations focusing on the opportunities and challenges associated with Smart Working or too focused on the practical technology and property related aspects?

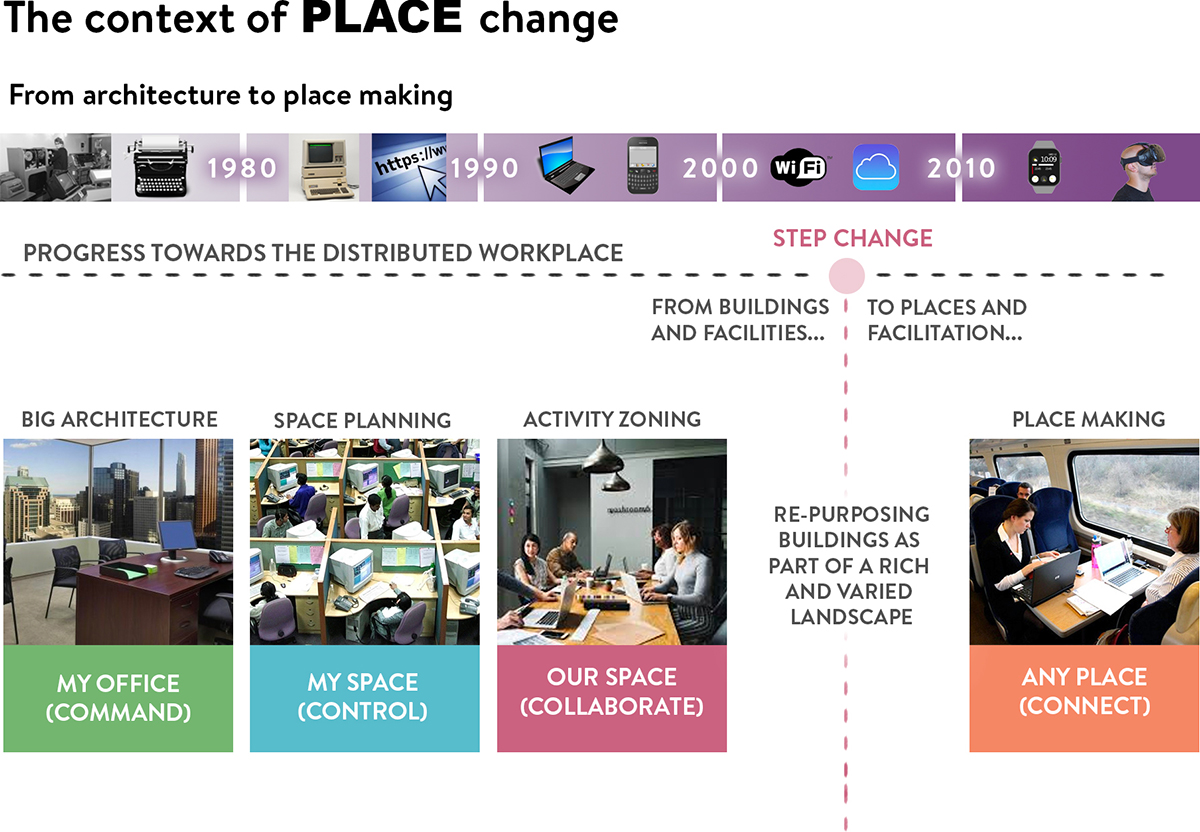

In my professional lifetime, the technology found in the average office workplace has evolved beyond recognition.

From the manual typewriters that were still knocking around even when the sophisticated ‘golf ball’ versions were the height of technology through to today’s sophisticated ‘work anywhere’ cloud-powered smart devices, the transformations and evolutions of the last few decades have taken us on an unremitting roller-coaster ride of speed and, at each introduction of newness, wonderment.

Back in the day when technology was formed largely of mechanical devices that simply assisted traditional methods of processing information, things were predictable and change was slow. The landscape of the typical office reflected a hierarchical ‘command and control’ management approach with clear departmental boundaries reflecting core professional specialisms.

Over time, however, all of that has become blurred, and organisations now need a rethink on how they operate and how they facilitate smarter ways of working. With the option to work anywhere now a reality for many, new codes of behaviours, new expectations and new types of interaction between employee and employer are demanded.

For those of us professionally supporting organisations in preparing for the future – by adapting their working practices and making better use of work ‘spaces’ to reflect the step changes that technology advancements are facilitating – we see a pattern of behaviour which is common across many sectors, whether private or public. Somehow the consequence of investment in technology on their tangible property assets is easier for them to comprehend and address than the intangible impact on their people and organisational culture.

Many regard allocating increasing proportions of their annual budgets to technology investment as something they simply have to do, often made more palatable by the promise that property rationalisation will contribute to such technology investment. Yet focusing on changing the way they implement changes of direction, changes in ways of working and changing expectations of what going to work actually means is often regarded as too complex and therefore given less (if any) attention.

More recently, the term Smart Working has been used to refer to the contributing factors that are changing how and where we work: the adoption of modern working practices made possible by advances in mobile technology, new contractual arrangements, more effective workplace environments and improved support service provision. When all of these elements are aligned, we are enabled to have more choice of where and when to work.

With the promotion of significant property rationalisation savings made possible by adopting Smart Working, it’s easy to appreciate why leadership teams seize on the opportunity to activate lease breaks, sell off freeholds or develop parts of their property portfolio for commercial gain. The race to explore and exploit those opportunities though often obscures the need to consider and carefully plan for the impact that such changes have on long-established ways of working. Too many organisations don’t factor in at all the significant benefits available if quality attention is focused on what are often – erroneously in my view – referred to as the softer aspects of change. Indeed, not addressing people-related issues puts the desirable benefits promised from technology investment and property rationalisation at risk.

So why don’t all Smart Working projects automatically include a balanced approach to change?

It may be that the tangible impact of change is simpler to articulate and the consequential benefits from investment decisions are far easier to measure and report than the intangible. And there appears to be nothing more tangible than property savings and technology investment.

What challenges this though is that many of the desired tangible benefits are dependent on the intangible interaction with people. Upgrading computing devices and software could be regarded as a tangible investment – but if people don’t understand how to use them to improve their working experience and benefit their productivity performance, neither the tangible nor intangible benefits will be fully realised.

The same can be said about the physical workplace. We can be persuaded that the replacement of desktop computers and landline telephones with laptops and mobile phones means the amount of space needed to work has shrunk. But if what’s retained is an unattractive, poorly equipped place that no one actually wants to spend anytime in at all, then the intangible value of ‘event’-based social interaction with peers and colleagues is lost as everyone will find somewhere more welcoming to spend their working time.

We need to shift expectation away from going to an often ‘joyless’ office every day (simply because we have no other choice) to a different set of beliefs and behavioural patterns that regard the office as just one of many places where we go to work – but one that is desirable, welcoming, stimulating and adds value to make it a worthwhile visit.

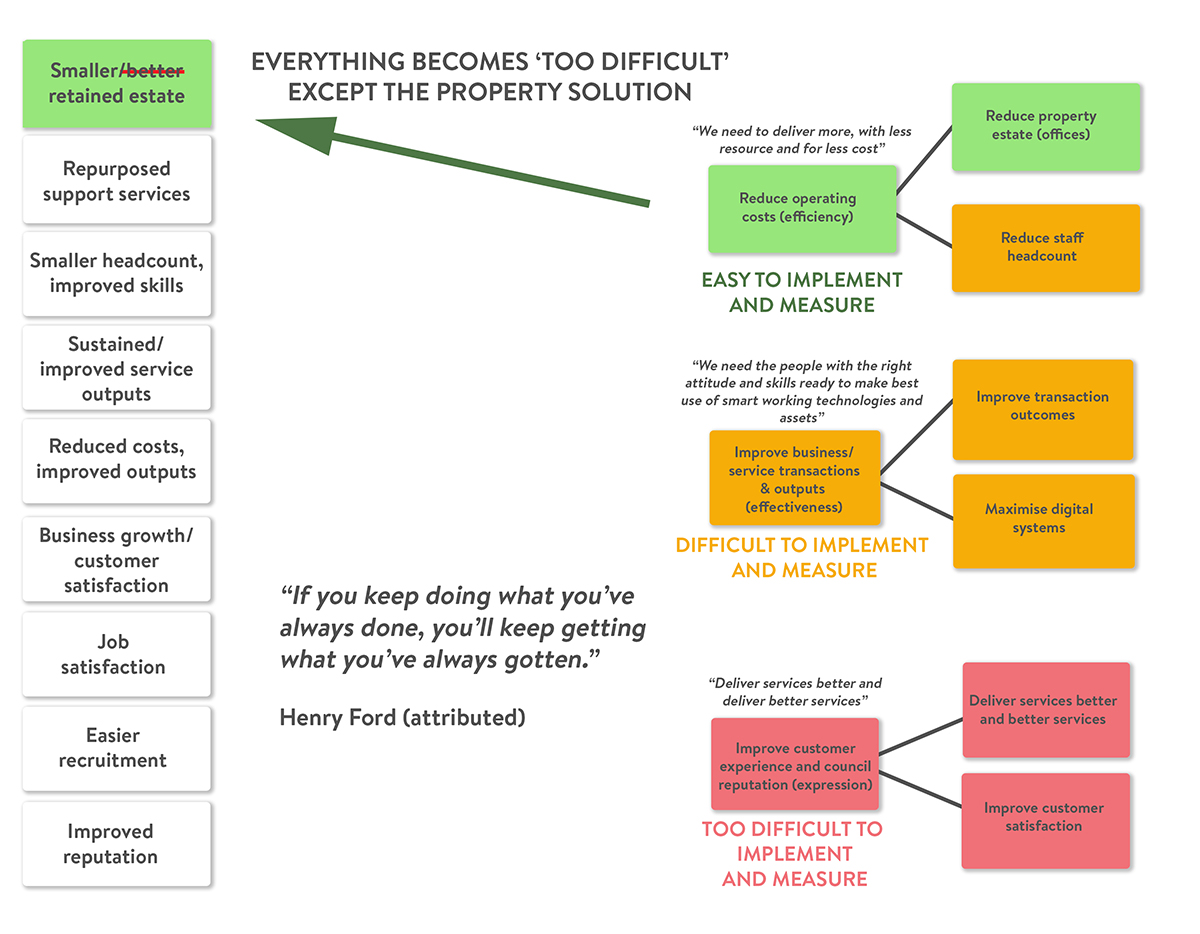

So what prevents an equal emphasis on intangible benefits as on tangible property and technology-focused benefits? Well, it appears that things often start going wrong just beyond the strategic vision stage.

Senior management is often clear on how adopting Smart Working will directly assist an organisation achieve its business objectives:

- Reduce operational costs (efficiency)

- Increase business transactions & productivity (effectiveness)

- Improve customer experience and business reputation (expression)

However, once this vision transfers to the implementation phase, the same old traditional siloed approach is all too often automatically adopted:

- Reducing operational costs and improving efficiency is assumed to be about rationalisation, and Property and HR lead on this.

- Increasing business transactions and productivity effectiveness is assumed to be about business improvement, so the PMO and ICT are assumed to lead on this

- Improving customer satisfaction: PR and Communications are assumed to lead on this.

If there is no recognition that implementing Smart Working demands an approach that cuts across all of these silos, then the results will be predictable: objectives become diluted versions of what the blinkered leads interpret for themselves as being desirable and achievable. The most tangible and measurable aspects of Smart Working, namely property rationalisation and technology investment dominate, and the wider intangible objectives – the ones regarded as more difficult to define, measure and report – become side-lined.

The risk of this approach is that the outcomes not only fall well short of the original objectives, but what actually gets implemented in fact damages the organisation. Yes, the property portfolio overheads are reduced, releasing and redirecting investment to new technology solutions, but adaption to new business practices and the nurturing of a new working culture are absent.

If we are all to benefit from advancement of technology and newer, better and smarter ways of working, then people need to be at the heart of Smart Working – and not on the receiving end of diluted outcomes.

Alison White

Co-Founder

PLACEmaking