In this exclusive, Ruth Richardson, Executive Director of the Accelerator for Systemic Risk Assessment (ASRA), calls on policymakers worldwide to transform risk management

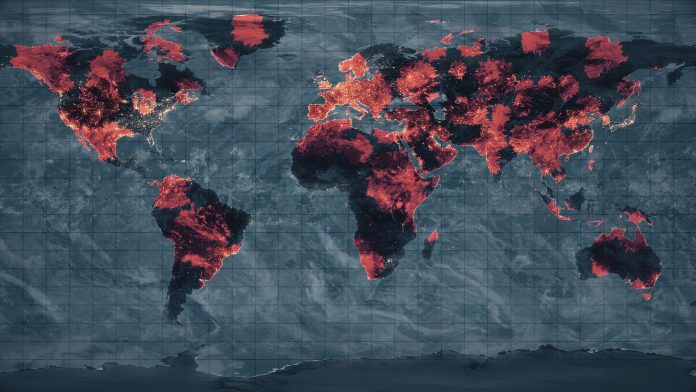

As our global polycrisis escalates, we face multiple and systemic challenges—from the climate emergency, biodiversity loss, pandemics, and the cost-of-living crisis, to the rise in conflicts, biological weapons, AI, and threats to democracy.

While it’s encouraging to see positive country-level initiatives, such as the UK Government’s ‘Prepare’ campaign, which aims to increase national resilience and strengthen community awareness of how to respond to emergencies, the stark reality is that more needs to be done.

This is supported in the latest Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll, which shows that 43% of people believe they are ill-equipped to protect themselves and their families in a disaster. Additionally, 30% have experienced a climate-driven disaster in the past five years, underlining the need for radical change in how policymakers anticipate and mitigate risks before they tip into shocks.

A fundamental part of the problem is that our current tools and strategies aren’t designed to assess the types of systemic risks that we face: risks that manifest as extreme global shocks, interconnect with one another, and turn into long-term crises. More often than not, risk assessment is siloed or focused only narrowly on certain issues or “known” problems.

This leaves decision-makers both blind in terms of understanding how a shock might spill into other systems—for example, from health to the economy, as we saw with COVID-19— and ill-prepared for those unexpected “what if” extreme events. An over-reliance on old and/or insufficient data to provide foresight, coupled with a lack of systems thinking and training within government and other sectors, further compounds the challenge.

In a polycrisis world, where challenges are complex and the path forward isn’t clear, our current risk assessment approaches fall short; something has to change. Inadequate analysis and the resulting poorly managed responses are not only costly for countries, communities, and citizens, resulting in a waste of time, money, resources, and even loss of life and livelihoods. They can also lead to damaged ecosystems and further undermine the wellbeing and resilience of the web of life upon which we depend.

What action can be taken?

From a policy perspective, innovative approaches and strategies are emerging to rethink governance approaches and, with that, how to mitigate and manage future risks. Examples include the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act in Wales, which mandates public bodies to think about the long-term impact of their decisions and to prevent persistent problems such as poverty and health inequalities which, in turn, become the drivers of systemic risk. Similarly, systems-based tools like the TEEB AgriFood Framework, which enables the measurement and valuation of food systems externalities, are practically aiding governments and businesses alike to make more informed and ecologically and socially sensitive decisions about their operations, and about what they support through subsidies and other means.

But we need to go further. We may not know the sequence of events that will lead to the next global shock, or those that follow, but we can take action now to assess and strengthen our responses, making our societies and institutions more resilient, equitable, and sustainable today.

This must start with governments taking immediate action by reviewing how risks are integrated into decision-making, including reassessing the evaluations that determine policy funding and the emergency response plans for disasters. We need a whole-of-government approach that not only delivers transformative efforts that reduce risk but also manage the potential cascading impacts of challenges that emerge. For example, one could imagine the appointment of a Minister for Systemic Risk in every country collaborating with the risk and resilience officers in other sectors and locations—including insurance, banking, energy, or at city-level—to share intelligence, generate new data, and empower all citizens to be active participants in decision-making and resilience-building.

On a larger scale, we need leaders to champion a new narrative which highlights our ability to transform the systems we’ve created for the better. Though this isn’t an easy task, in these times of polycrisis, it’s crucial to recognise that quick-fix “solutionism” isn’t the answer. The challenges we confront are intricate, and the path forward is uncertain. Yet as we have seen multiple times in history, we must not underestimate the capacity and capability for humans to forge a future where all people, societies, and ecosystems can thrive.

To do this well and make it practical, policymakers need to embrace known and effective modes of citizen engagement and participation. This includes citizen assemblies or participatory budgeting, to create the systems that connect decisions about risk management with people’s needs and values. Not only will this help the public in understanding these risks, but better inform government decision-making, and mobilise and empower individuals to bolster their own and their community’s resilience.

Our multiple global challenges are interconnected and must be treated as such. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the problem with siloed thinking. Initially, the short-term, precautionary response was straightforward: “flatten the curve”. Yet, as the crisis unfolded, unforeseen and cascading consequences emerged, impacting education, mental health, and social equality. We are still feeling the reverberations of all of this four years later. Similarly, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlighted the interconnections between conflict, energy, food production, and migration, playing a fundamental role in triggering the cost-of-living crisis that persists.

The escalating global polycrisis demands an urgent and transformative shift in how we assess, anticipate, and mitigate systemic risks. While certain initiatives provide glimpses of hope, they are not enough on their own. It’s time to harness our resources and tools to assess risks proactively, strengthen proven disaster prevention and risk mitigation strategies, and shift mindsets from fear, paralysis, and despair to hope, action, and determination. Systemic risk assessment is a vital catalyst to drive progress on all fronts.