Scientists invented the ‘falloposcope’ to detect early-stage ovarian cancer – now, making history, a surgeon successfully used the device to capture images of fallopian tubes

Over three out of four ovarian cancer cases are not detected until the cancer is in an advanced stage due to a lack of effective screening and diagnostic tools – sadly, fewer than half of all women with ovarian cancer survive more than five years after diagnosis.

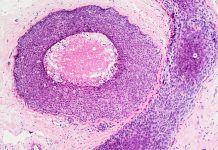

Now, having spent a decade researching, researchers have developed a device small enough to image the fallopian tubes, which are narrow ducts connecting the uterus to the ovaries, which can help point out any signs of early-stage cancer.

A decade in the making

Researchers have now used the imaging device in study participants for the first time. As part of a pilot human trial, the falloposcope device was used to image the fallopian tubes of volunteers.

These volunteers are already having their tubes removed, for reasons other than cancer.

This allows researchers not only to test the effectiveness of the device, but also to start establishing a baseline range of what “normal” fallopian tubes should look like.

The devices efficiency is from its multiple imaging techniques, for instance, a method called fluorescence imaging – which measures the way different molecules absorb and emit light – the device can analyse metabolic and functional changes in tissue.

Additionally, with optical coherence tomography, the device observes structural changes at high resolution. Another technique it uses is white light reflectance imaging, where it gathers information about tissue based on the way it reflects light.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stated that the study has “nonsignificant risk,” however, testing the device on an organ that is about to be removed reduces the risk even more. Yet the pilot researchers have already successfully, and safely, used the falloposcope in four volunteers.

Heusinkveld, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynaecology, said: “This is the first endoscope that can fit inside a fallopian tube and actually see anything below the surface with high resolution. We were very pleased with the images the device was able to capture in its first inpatient uses, and we look forward to gathering more data.”

20,000 US women will receive diagnosis of ovarian cancer this year

At 0.8 millimetres in diameter, the falloposcope is extremely small in size.

Describing it as “itty bitty”, researchers highlight the scientific breakthrough that this project entails, stating: “You just couldn’t have fabricated something like this, even six, seven years ago.”

It is estimated by the American Cancer Society about 19,880 women in the United States will receive a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and about 12,810 will die from the disease just in 2022. The researchers express hope for the potential of the falloposcope, which could help save the lives of some women and vastly improve quality of life for others.

Can early stage detection change treatment options?

With early-stage detection, doctors could perform prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies – which is the removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes – before ovarian cancer spreads.

Researchers believe that ovarian cancer generally begins in the fallopian tubes, so it is often advised by physicians for women at risk for ovarian cancer have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed.

Though this invasive surgery does have potentially lifesaving benefits, it also has its drawbacks – often causing side effects of hot flashes, mood swings, and higher risk of heart and bone disease, as well as causing women to have surgically induced menopause.

In one example, a study with 122 patients – known carriers of genes that increased their risk for cancer – had their fallopian tubes removed as a precaution. The researchers used this analysis example of the tubes after removal, which showed that only seven of the women were in the process of developing cancer.

Giving women a safer option than ovary removal

Regular falloposcope screenings entail that even patients who do ultimately opt for the removal procedure could have it done later in life – even after their childbearing years.

The research team hopes to image at least 20 sets of fallopian tubes before removal, and the surgeon, Heusinkveld, will provide feedback to the engineering team about how to make the device easier to use and more effective.

Barton said: “This device could allow us to tell those other 115 women, ‘Hey, you are perfectly normal, and we’ll come back and check on you every couple of years to make sure everything is OK.”

Heusinkveld further said: “Anecdotally, I can tell you that when a patient has her ovaries removed at a young age – almost always for cancer risk reduction – she is placed on supplemental hormones, and a significant percentage of them come back and say, ‘You know, I just don’t feel as good as I did.

“And there’s nothing you can do about that, aside from fiddling around with dosage. So, if we can delay removing ovaries until an age where they’re truly inactive, that’s going to be a pretty big health benefit.”

The team want to establish “what normal looks like”

Barton said: “The goal here is to show that we can get into the fallopian tubes – which is nontrivial itself – take images, assess the quality of the images and get physician feedback. This study will help establish a baseline of the range of what ‘normal’ looks like.”

The team’s goal for the future is to use the device to image fallopian tubes in patients with a high cancer risk.

Though it will take time for it to be approved by the FDA, as well as be manufactured and become commercially available, this ground-breaking device is an important milestone in the process could ultimately change ovarian cancer screening protocols forever.

Is this new device to be used for woman like me in remission, and are afraid of reoccurring Overian Cancer.