Diana Agacy, Blood Transfusion Nurse Practitioner and Phlebotomy Manager at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation gives an overview of the importance of patient safety during blood transfusions.

As a transfusion practitioner, the main aspect of my role is to educate healthcare professionals in safe transfusion practice and the first thing that I was taught by my blood bank manager was that “the safest blood transfusion is the one not given”. This, to me, was an oxymoron. I had worked in oncology and critical care and had seen the benefits of blood transfusions.

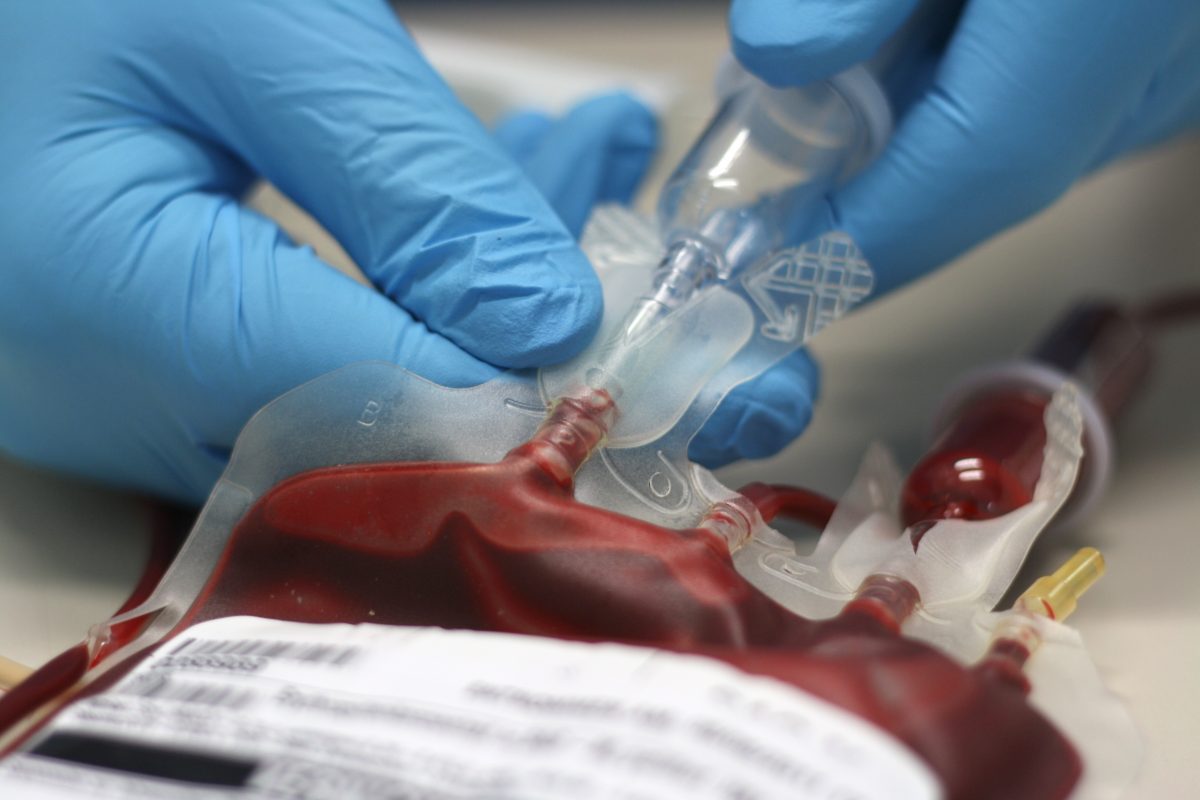

Within the transfusion community it has been widely recognised that the biggest risk in transfusion practice is the result of human error – the biggest risk being the wrong blood being transfused to the wrong patient. This usually occurs if the final bedside check prior to transfusion is not carried out as per guidelines. Transfusing the wrong blood type is also associated with errors at the pre-transfusion sample taking stage. This happens when the healthcare professional takes a sample from one patient but then labels it with another patient’s details, wrong blood in tube (WBIT) category in SHOT. This usually occurs because the pre-transfusion sample label is not filled in at the patient’s side, after the patient has been bled. The healthcare professional must always check that the information on the sample label exactly matches the information on the patient’s identification band or has it confirmed verbally by the patient before completing the pre-transfusion sample taking phase of the transfusion process. The general public, however, perceive the greatest risk of a blood transfusion is a blood borne infection.

The quality of the most frequently transfused blood components (red cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are of the highest standard thanks to the Blood Safety and Quality Regulations 2005, both in hospitals and at the point of manufacturing. The evidence from the Serious Hazards of Transfusion Haemovigilance Scheme (SHOT) is proof of this. Approximately 3 million components are issued per year. The figures of major morbidity risk per component are as follows:

Hepatitis B (Public Health Data) 1 in 1.3 million

Hepatitis C 1 in 28 million

HIV 1 in 6.7 million

However, patient safety in relation to blood transfusion has to be appropriate use of blood and, unfortunately, traditional liberal transfusion practice is hard to challenge.

A red cell transfusion is considered appropriate when the patient’s bone marrow is dysfunctional or when there is a severe life-threatening bleed that jeopardises the oxygenation of the vital organs. Red cell transfusions should never be used to treat chronic anaemia unless there are associated symptoms of acute anaemia. Chronic anaemia is a sign of an underlying pathology, it is not a diagnosis. The underlying disease which is causing the anaemia must be diagnosed and treated.

Platelets have their uses but using these outside the recommended guidelines can be detrimental and a waste of a precious resource. The effectiveness of FFP is also being questioned and it is often used incorrectly. These 2 components are used to stop bleeding based on laboratory results done in vitro. The evidence which is emerging implies that these tests do not reflect their true action within the human body and a good bleeding history from a patient is more beneficial to avoid bleeding in elective peri-operative cases. All of the above are addressed in the training and education of doctors; however, it is very difficult to demystify culture.

This is where patient blood management (PBM) is pivotal and it is the task of the transfusion practitioner, backed by the hospital transfusion committee, to educate healthcare professionals in the acute setting about PBM. In the community setting, the challenge is to educate general practitioners about iron preoptimisation before referring a patient for elective surgery. Pre-assessment clinics, regardless of speciality, should not accept patients that do not meet the optimal haemoglobin level for elective surgery. Optimal haemoglobin levels and good surgical techniques reduce the need for postoperative transfusions and length of stay in hospital. This is summarised in the 3 Pillars of Patient Blood Management, available here: www.health.wa.gov.au/bloodmanagement/docs/pbm_pillars

Lastly, the 2 simplest but most effective patient safety measures in blood transfusion lie with the patient and their next of kin. To avoid human errors, patients must take ownership of ensuring that their demographics are correct on the hospital patient administrative system by checking that the information on their identification wristband is correct, if not inform a member of staff immediately, and wear it at all times while in hospital. The ‘Do you know who I am campaign?’, based on 2009 SHOT recommendations, is available here:http://www.pifonline.org.uk/blood-transfusionawareness-campaign-do-you-know-who-i-amlaunches/

Diana Agacy

Blood Transfusion Nurse Practitioner and Phlebotomy Manager

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

Tel: 023 8120 8910