Katharine Jenner, Campaign Director and Mhairi Brown, Policy and Public Affairs Manager of Action on Sugar and Action on Salt, debate who should be responsible for tackling the biggest cause of premature death and disability in the UK when Public Health England is dissolved

In 2002, Derek Wanless gave HM Treasury a vision of what our health system could be like in 2022, a future where ‘levels of public engagement in relation to their health are high. Life expectancy increases go beyond current forecasts, health status improves dramatically and people are confident in the health system and demand high-quality care. The health service is responsive with high rates of technology uptake, particularly in relation to disease prevention. Use of resources is more efficient.’

The scenario illustrated that lifestyle changes such as stopping smoking, increased physical activity and better diet could have a major impact on the required level of health care resources, with better investment in delivery (local, regional and national) and government as the regulator, ensuring taxpayers’ money is being used efficiently and effectively.

COVID-19

Wanless neglected to mention a major pandemic in his modelling, more’s the pity. Perhaps if he had, he would have urged the Treasury to push for greater and urgent investment in public health, so we could have come into this virus in better health, better prepared. Data has revealed that preventable health conditions such as obesity and high blood pressure, as well as inequalities, age and ethnicity, are all risk factors for severe illness and death as a result of COVID-19.

And those preventable health conditions have been rife in the UK for decades. People are actually dying from malnutrition in this country, not just from a lack of food but from a lack of ‘good’ food. Nutritionally poor diets – too much salt, sugar and saturated fat; too little wholegrains, fruit, vegetables and fibre; and drinking too much alcohol – are the biggest cause of premature death and disability in the UK.

Nutrition-related ill health

The more socially deprived are much more at risk of suffering from nutrition-related ill health. Young people from poorer backgrounds are more likely to have obesity, consume a range of less healthy food and drink and be exposed to more adverts promoting unhealthy food. There is also a huge, often ignored personal cost; those living with obesity are more likely to suffer with their mental health and face stigma, worsening their prospects and productivity in all areas of life. A clear and unequivocally devastating impact on our health and our economy.

Reformulation

Reformulation to improve the nutritional profile of food and drinks, by gradually reducing salt, sugar and saturated and trans fats while ideally increasing wholegrains, fibre, fruit and vegetables, is a cornerstone of prevention policy worldwide; a powerful and cost-effective tool in the prevention of ill health. Reducing salt, sugar and calorie intakes would save, by the government’s own conservative estimates, at least £7.5 billion and would prevent 50,000 premature deaths a year. The Soft Drinks Industry levy (SDIL), brought in by George Osborne and implemented by the Treasury, has raised £485 million over the previous Spending Review period, removed more than 90,000 tonnes of sugar from our diets, and actually increased sales in the sector. Win for government, win for health, win for business and all without us mere humans having to make a tough choice – the dream triple ‘nudge’.

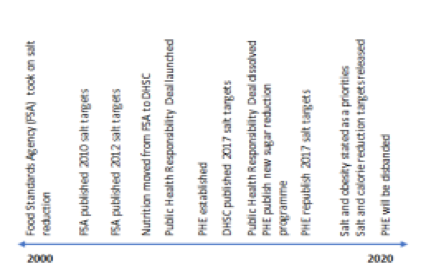

When Wanless authored his report in 2002, the Food Standards Agency was just getting going on the UK’s first reformulation programme (salt reduction), which would become known as one of the greatest cost-saving cardiovascular disease prevention programmes in the world, but for a limited time only though. Fast forward to 2020 and we’ve experienced 18 years of government passing the buck on public health to arms-length bodies. Nutrition, smoking, alcohol, drugs and even mental health programmes get passed from pillar to post, losing traction, accountability and impact along the way [Figure 1]. We have watched the salt reduction programme go from world-leading at the Food Standards Agency, to an embarrassment as part of DHSC’s Responsibility Deal, to a footnote in history at Public Health England.

Prevention Green Paper

Matt Hancock, at least, hasn’t let these failures get him down. As stated in his Prevention Green Paper – prevention is better than cure. Salt reduction is a key promise set out to be achieved in that paper and calorie reduction even made it into Boris’ obesity plan. Can we dare to hope that the political will for prevention is finally here? The real measure of government support – investment – tells a different story. Public health expenditure has been cut, cut, and cut. The public health grant in 2020/21 was 22% lower per head in real terms compared to 2015/16. The IPPR say areas with the highest COVID-19 mortality experienced 3.5 times more public health cuts since 2014 than areas with lowest. It’s clear that in the government’s eyes, prevention is better than cure, until you have to pay for it.

Now Public Health England’s doors are closing and there is no agreed plan for health improvement, promotion, and certainly not prevention. Several options have been laid out on the table by DHSC, and we have been fortunate to have discussed them with a variety of stakeholders involved in the decision-making process and some of the brightest minds in prevention. There are many elements we all appear to agree on, particularly that the current silos of Government departments cannot continue – health policies may be overseen by DHSC, but the work of all departments impact health. Cross-department working with clearly defined roles and responsibilities must be the way forward, built on a bedrock of purpose-driven values, developed collaboratively with agreement from all parties. We also believe a governance mechanism is vital.

A new, independent authority should be established to:

- Report directly to Parliament and provide necessary, transparent scrutiny of progress

- Work across all devolved nations, providing national leadership to deal with national and multinational influences

- Ringfence funding until at least 2030, as public health decisions affect a generation, not a political term

- Have freedom to speak to the evidence and make evidence-based recommendations to ensure continued progress, without influence

It doesn’t matter what you call the ‘new PHE’ though– decisions are ultimately made at the top, and the decision-makers need recommendations that are based on evidence, free from the many vested interests. From Osborne overruling industry to introduce the SDIL, to Theresa ripping up Cameron’s obesity plans, to Boris giving a select few obesity prevention measures that appeal to his sensibilities the green light (…but not until 2022).

The UK has an opportunity to be world-leading again, with the potential of developing and implementing mandated national nutrition improvement measures like the SDIL to replace the current voluntary programmes. Improving nutrition is good for individuals, good for the economy and, as we have seen with the SDIL, can even be good for business. It’s not too late to make Wanless’s vision of a society that prevents, not just treats, disease a reality – we just need government to recognise what we all know; that public health is an untapped treasure trove.