Professor Ghulam Nabi from the University of Dundee explores the subject of the enigmatic prostate cancer, with different shades

Prostate cancer accounts for nearly 27% of all newly diagnosed male cancers in the European Union, with 130 new cases detected every day in the UK. Despite significant improvements in the early detection of disease, almost six in 10 men with prostate cancer are diagnosed in their late stages.

Diagnosis of prostate cancer is usually made by physically examining the man’s back passage (digital rectal examination) and a blood test aimed at an estimation of a protein which comes from the prostate gland, though not necessarily from cancer, called a prostatespecific antigen. The presence or absence of disease is confirmed using ultrasound-guided biopsies.

At least 10 biopsies take place and it is necessary to take a sample from the gland in this way due to the inability of conventional ultrasound technique to pinpoint the location of cancerous lesions within the prostate. Our group at the University of Dundee believe we have found a new method offering more successful diagnosis and management of prostate cancer, however.

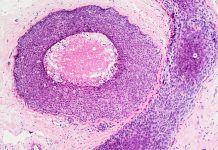

Shear Wave electrography-based ultrasonography techniques are a new way of detecting the disease. The technique creates shear waves within the gland and then measures their velocity as they spread around the tissues. The speed of these waves is affected by the stiffness of the tissues. Cancerous lesions are stiffer than healthy tissue due to the disorganised growth of cells and these are highlighted as red on the screen (see figure 1).

Prostate cancer is a spectrum ranging from very slow indolent cancers to the most aggressive types of the disease. The challenge in prostate cancer is not only early detection, but also assessing which cancerous lesions are aggressive so that treatment plans can be personalised.

There are various types of curative treatment options for disease localised to the prostate gland and these range from needle treatment of the lesions to complete removal of the prostate gland during surgery or treating using radiotherapy. The later can be achieved by focusing rays from outside (external beam) or placing radioactive material within gland in the form of seeds (brachytherapy).

The technique of SWE we have described provided early detection of cancerous foci within the gland, pinpointing of these lesions and a degree of aggressiveness by quantitative measurement of the degree of stiffness, the redness that appears on screen. Using a simple, office-based test such as ultrasound should provide a degree of confidence in risk-stratifying men into different pathways and therapeutic options.

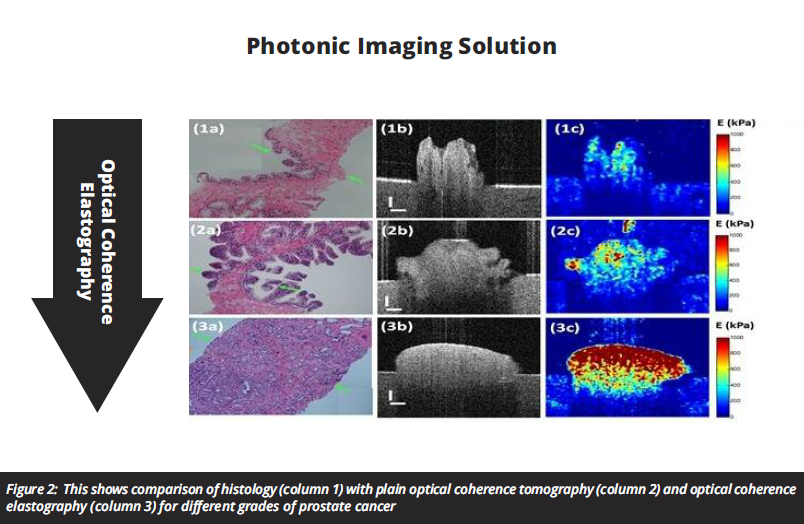

Assessing response or real-time monitoring of therapy is the equally important aspect of prostate cancer treatment. Our group in Dundee is the only dedicated consortium which has published work in optical coherence elastography (OCE). The latter is another way of assessing tissue stiffness using a specific wavelength of light. The way tissue handles the passage of light through it can provide invaluable information and can be used to through needles to assess real-time change in tissue stiffness (see figure 2).

Taken together, it is like someone has turned the lights on in a darkened room. We can now see with much greater accuracy what tissue is cancerous, where it is and what level of treatment it needs.

This is a significant step forward in detection and management of prostate cancer. We really need to see this looked at on a wider scale to build more data but there is clearly the potential to really change the way we manage prostate cancer.

Professor Ghulam Nabi

M Ch, MD, FRCS (Urol)

Professor of surgical uro-oncology Hon.consultant urological surgeon

Clinical Head of Division of Cancer Research

Lead for Prostate Cancer Surgery, NHS Tayside

Chair Tayside Urological Cancers Network (TUCAN)

University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee

Tel: +44 (0)1382 660 111