The UK must improve the way it decides between infrastructure finance options if it wants to pick the best value finance options, argues Graham Atkins from the Institute for Government

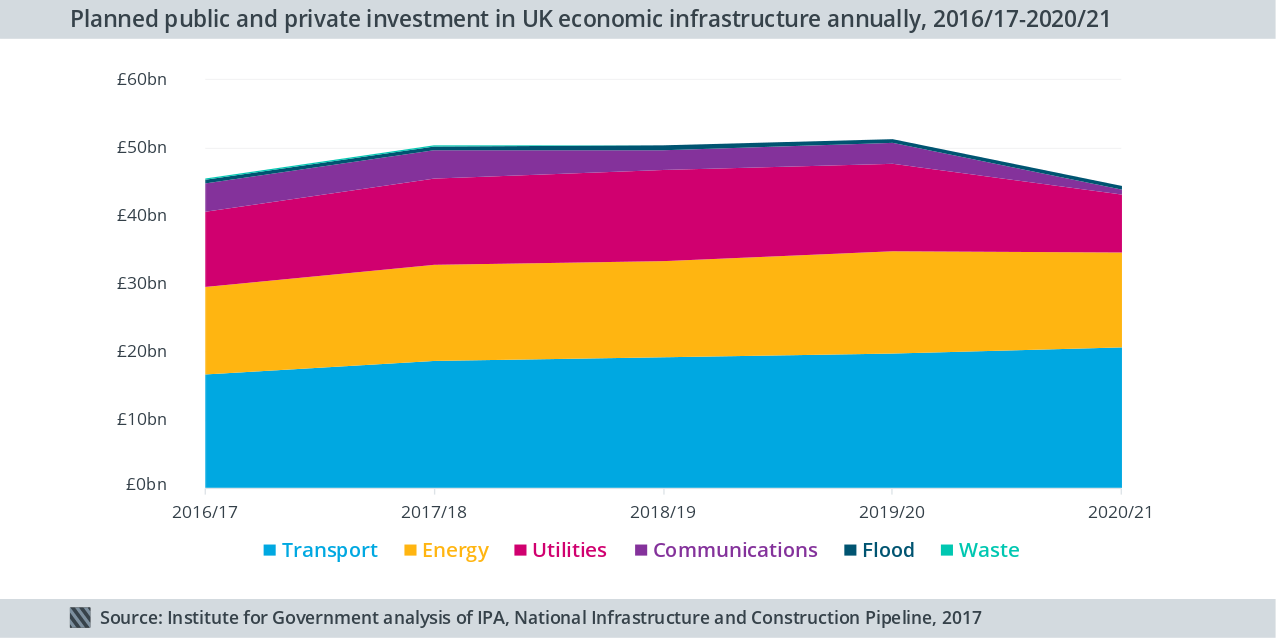

The UK government is planning for £242 billion of public and private infrastructure investment between 2016/17 and 2020/21 (see fig. 1).

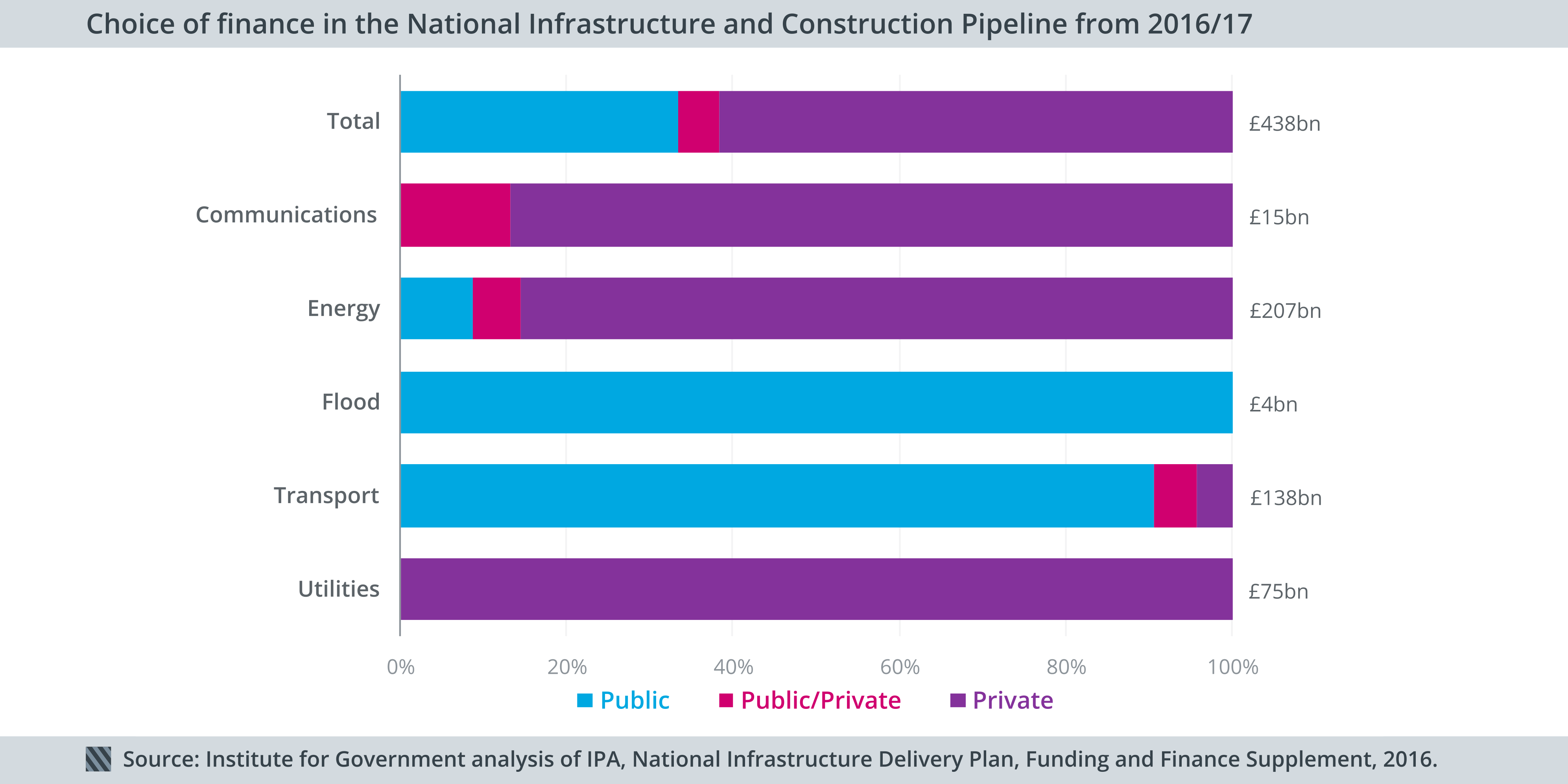

A large number of these projects will be privately financed – primarily those in energy, utilities and communications (see fig. 2):

The government needs finance to meet the upfront costs of a range of new projects. But in the past, governments have not made good finance choices. There are examples of success, such as Thames Tideway, but there are many examples of inappropriate finance choices leaving taxpayers and consumers locked into expensive and inflexible contracts.

Governments struggle to pick the options which deliver the best value over the long-term. A recent Institute for Government report, Public versus private: how to pick the best infrastructure finance option, identified three key challenges the government faces when trying to select the best finance options:

Accounting

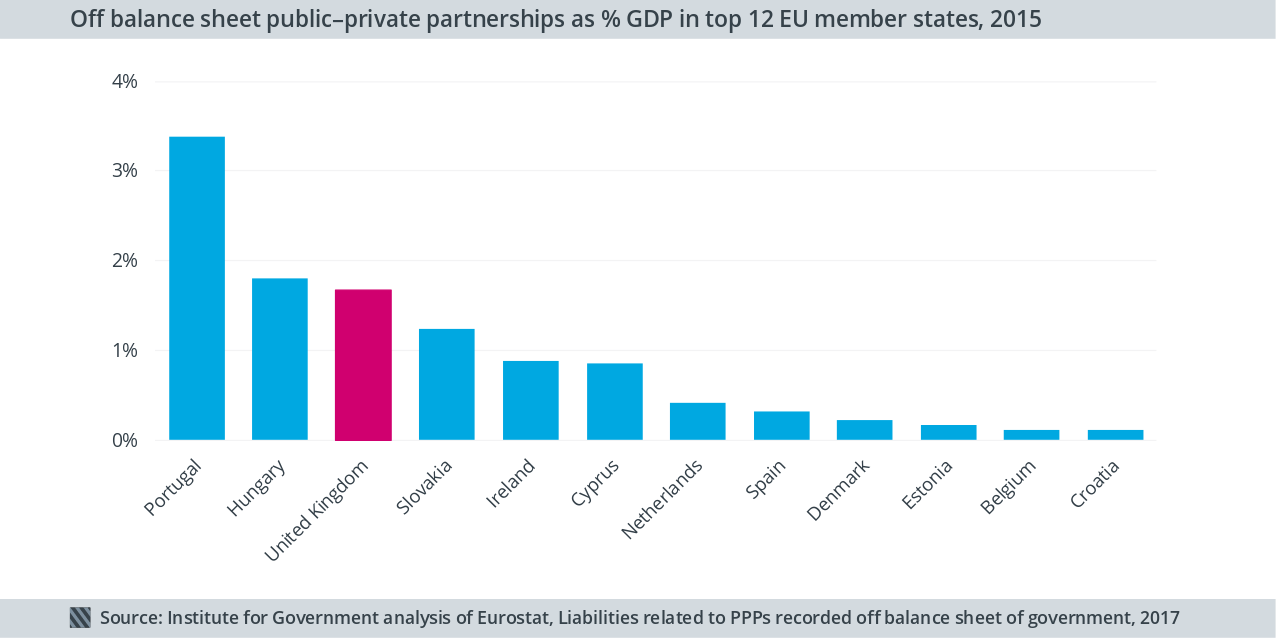

The UKs accounting standards mean that 90% of private finance projects do not count towards public sector debt. Being effectively ‘off balance sheet’, ministers may choose to use private finance because it does not contribute to public sector debt, rather than it being any better value.

The government cannot let arbitrary accounting rules and narrow fiscal targets drive financing decisions. ‘Off balance sheet’ projects will not always be the best value, especially if the government tries to transfer risks or uncertainties which it is better placed to bear.

For example, past private finance contracts have limited public ownership and transferred construction risks, even in highly complex projects. This appears to have been to ensure off balance sheet treatment.

The UK has more off-balance sheet private finance projects than most other European Union countries (see fig. 3).

To mitigate the impact of partial accounting undermining comparisons between finance options, public authorities must publish their comparison of finance options using wider measures of public sector debt and liabilities. Being transparent about the assumptions and the evidence underpinning comparisons would allow informed auditors to improve decisions.

In addition, the Chancellor should expand the fiscal remit of the National Infrastructure Commission to include private finance. Expanding the remit would reduce the temptation for ministers to choose private finance to game spending targets.

Appraisal

The government must compare finance options fairly. Appraisal would be improved if it were underpinned with the latest data on the costs and benefits of different finance options. The starting point is data collection. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority – the government’s centre of expertise on private finance – should mandate departments to collect and collate evidence on the cost and quality of past publicly and privately financed projects.

At present, the multiple responsibilities of those comparing finance options undermines assessment. Project teams who compare options are often intimately involved in the project and usually have preferences for it to be publicly or privately financed.

Because of the lack of data, these teams and their consultants have ended up relying on their own experience to predict the likelihood and impact of certain risks. This is not good practice. Relying on the perceptions of people closely involved with specific project risks underestimating the costs, times and risks of their favoured options.

Those undertaking appraisals must have the incentives in place to provide objective advice. Creating separate teams within departments, or a separate team within the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, would improve the current situation.

Budgeting

Even where private finance is likely to deliver less value compared with public finance, the way the Treasury allocates money incentivises departments to use private finance. Private finance has a faster sign off than standard capital spending, short spending reviews make public finance uncertain and limited capital budgets can make private finance look unduly attractive.

To avoid this the Treasury must plan capital budgets on a longer-term cycle, assuming that the government will spend 1-1.2% of GDP on economic infrastructure every year – the same remit given to the National Infrastructure Commission.

Within that 1-1.2% commitment to infrastructure, some money must remain unallocated, so that it can be used for projects which emerge outside of Spending Reviews. Without some fiscal headroom, there would be a danger of defaulting to private finance for these projects.

The UK can improve the way it decides how to finance infrastructure projects. Decisions about how to finance infrastructure projects must be based on evidence that the financing option selected will deliver the best value. They cannot be based on arbitrary accounting rules or anecdotes.

None of these challenges are insurmountable and the reforms the Institute for Government outline will help the government pick the best finance options more often.

Graham Atkins

Researcher

Institute for Government

Tel: +44 (0)20 7747 0422