Steve Haskew, the Group Director of Sustainability at Circular Computing – an organisation that sits at the centre of the circular economy – discusses the possibilities of remanufactured IT in the NHS

Circular Computing sits at the centre of the circular economy within the space of laptop technology.

Their vision is that a decarbonised future doesn’t exist without a circular economy because 85% of the carbon emitted from a laptop comes at the production end.

Open Access Government interviews Steve Haskew on how we can aid the significant saving in carbon output from this sort of technology, to which he argues, remanufactured IT is at the centre of the social economy.

Circular Computing is the only organisation on the planet that can remanufacture laptops to a condition that’s been defined by the British Standards Institution that is equal to, or better than new.

1. In your view, how has the NHS come to face its current financial troubles?

The NHS has a problem currently in that it’s underfunded. But no matter what it needs to continue providing mainline support for its core service, which is helping the public with healthcare. In doing so it, therefore, needs to ensure it applies its limited resources very carefully so that it’s able to do more of what it’s being tasked to do.

When looking at its technology – which in the NHS is a wide subject – along with the medical equipment, it probably has a million laptops within the organisation, a good estimate of the size of the NHS laptop estate.

The average cost of a new laptop could be anything up to around £1000, but perhaps for the sort of product they often need, there should be a way that they can save money on their IT procurement. They can then apply these savings directly to the core areas of their service like public health care.

We have a proposition where even if they were to consider not buying a brand new one, but instead buying a remanufactured IT solution, there’ll be a 40% saving immediately against the cost of buying brand new.

40% worth of savings when buying remanufactured IT

The supply chain is also resilient, so they’re not at the mercy of the existing supply chain, which has been proven to be dangerously unreliable as of late. If you look at COVID and how things have been with regard to supply, it’s dangerously precarious.

Despite the current new product supply chains being unreliable, the existing laptops they currently have are often dated and tired. So, if there’s a way of bringing the laptops that already exist in their estate back to a like-new state such as through remanufacturing, then there are immediate savings benefits for the organisation. Rather than paying £1000 for a new device, they would only pay £150, let’s say, to have the current devices remanufactured.

In the same way that you wouldn’t buy a car, drive it for three years, and then when the tires need replacing or the servicing needed to happen, just throw away the keys and buy a brand-new car. Instead, you get a service to extend the life of the car – the same logic can be applied to laptop technology, and that’s where we sit.

2. What are your ideas for a tech procurement strategy?

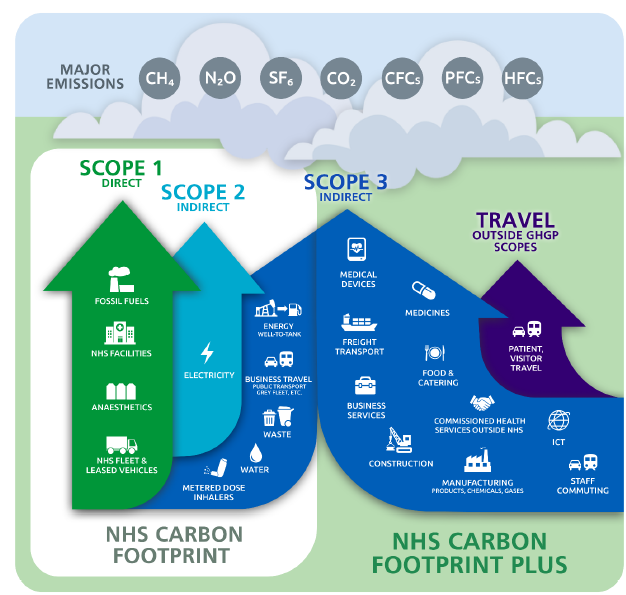

A procurement strategy should first look at sustainable outcomes as a prerequisite. If you have a look at the NHS Digital strategy, and the greening of its organisation, they often look at carbon savings as a key driver to any procurement.

The challenge is that the key stakeholders within a large organisation like NHS Digital sometimes find it difficult to align the overall climate agenda with their individual position. Procurement obviously is incredibly compliance dependent and there are many stakeholders in the procurement of goods for the NHS that are all bound by law.

There are many layers to the category manager specifying that they want this or that sort of product. It has to go through a framework, and then go through the legal procurement process, which can somewhat slow things down.

When organisations are looking to do a better job of procurement, but are restricted to legacy systems, we often see that to be a barrier. I don’t think anybody comes to work wanting to do a bad job or do a worse version of yesterday but they sometimes find embedding sustainability within procurement a challenge. The two things can be juxtaposed. The default position for procurement is to go back to business as usual, which is to buy in a linear way.

The default position for procurement is to go back to business as usual, which is to buy in a linear way.

That linear way then has a habit of outputting carbon, and that then runs against the overarching strategy of the organisation to make these carbon savings.

Yet procurement is either not aligned to that or not aligned as quickly as it needs to be, and it could even be locked into a framework that has a four-year time window on it, which for me is kind of crazy. If the existing framework that they buy through, let’s say, has a 2025 renewal date, they are bound by the legalities of that framework, even though they know they’re pouring petrol on carbon emissions, which affects climate change.

I find that to be a little bit discomforting. Everybody knows climate change is a pressing issue, everybody knows there needs to be a change of behaviour and everybody’s hiding behind the curtains. They say it’s too difficult and that they’ll carry on as they are, knowing that what they’re doing works against the climate ambitions of the organisation.

3. How can remanufactured IT makes an impact on the NHS’s sustainability goals?

We have evidence from peer-reviewed work that we’ve done with Cranfield University that if you remanufacture a laptop, the carbon emissions are about 6% total in comparison to that of a new device. That’s a 94% carbon saving immediately.

We still do have a small footprint, because it’s very hard to be both cost-effective and use logistics partners that have adopted sustainable aviation fuel, and we’re reliant on certain technologies to be more mainstream and more affordable. And we’ve therefore invested in an offset investment programme with renewable energy programmes that are a gold standard to take care of our small footprint.

But what this all looks like in practice, is that the difference between brand new and remanufactured IT and Circular Computing products is about 316 kilos of CO2 per laptop.

So, for every three laptops that they buy, they could save a tonne of CO2. And just to put that into a frame, a tonne of CO2 for most people doesn’t mean a lot, but it’s equivalent to 19,000 cubic feet. And 19,000 cubic feet will fit into the air mass of a three-bedroom house, plus or minus in the UK.

For every three laptops that they buy, they could save a tonne of CO2

That’s the net effect you’re effectively letting off every time you replace three existing laptops with brand new ones. At the scale of the NHS, a million devices would equate to 300,000 tonnes of carbon being emitted every time the estate is replaced.

What we want to say is that there are already sustainable IT solutions available to the NHS and that’s not even pecking away at the fact that there’s a resource preservation issue with buying brand new that is so significant that the pressure being put on planetary reserves is a real problem.

The circular economy is looking to preserve what’s already been made, be regenerative in resources and zero-out waste and if that’s part of the future, then we have a solution that can be applied today that is an easy shoe to put on. Our biggest challenge then is to move the needle of perception.

When you think of a second-hand laptop, you probably think of a second-hand shop on the high street selling products that probably haven’t been looked after properly and it’s just on the shelf nowhere near the quality of a new item.

Whereas with what we do, the remanufacturing process disassembles the asset down to its sub-component layer. It tests those sub-components, rebuilds, replaces, or remanufactures those sub-components, and then rebuilds them back to a brand-new quality.

Eventually, for all intents and purposes, the new user wouldn’t know that it’s not a brand-new product.

There’s also the fact that just because the manufacturers today are constantly putting onto the market products with the latest modern intel chip, doesn’t necessarily mean that the latest new intel chip is required by most users. For the majority of people in white-collar work like the workers at NHS, often don’t need the firepower.

The digital strategy adopted by the NHS needs less first-hand technology

What’s happening is the digital strategy adopted by the NHS is being put on to them by the supplier of the brand-new technology, whether they like it or not. Whereas what we’re saying is, a three-year-old device actually can handle the workloads you’re putting on it.

It is what you need, it just needs to be brand new again, it needs to come with a warranty, and you need to be protected as a user. All of those are things that we can do.

So how can remanufactured IT impact the NHS and its sustainability goal? They can look at resource preservation and they can also look at a reduction in water consumption. If you think about from mine to market, to produce a product from the ground up, brand new, you’re going to use roughly 190,000 litres of water per device to mine the material, to manufacture the material and to get that product to market.

If you don’t do that then there are 130,000 litres of water that can be used for something else. While in the Western world, if you turn the tap on there’s water – in places that are starved of water, it’s a real difference.

In situations where the water supply has been diverted to manufacturing sites, then this means the water can instead be used for farms for food and you can start to create a more sustainable society. So, we are heavily aligned towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and therefore can also impact the NHS as such.