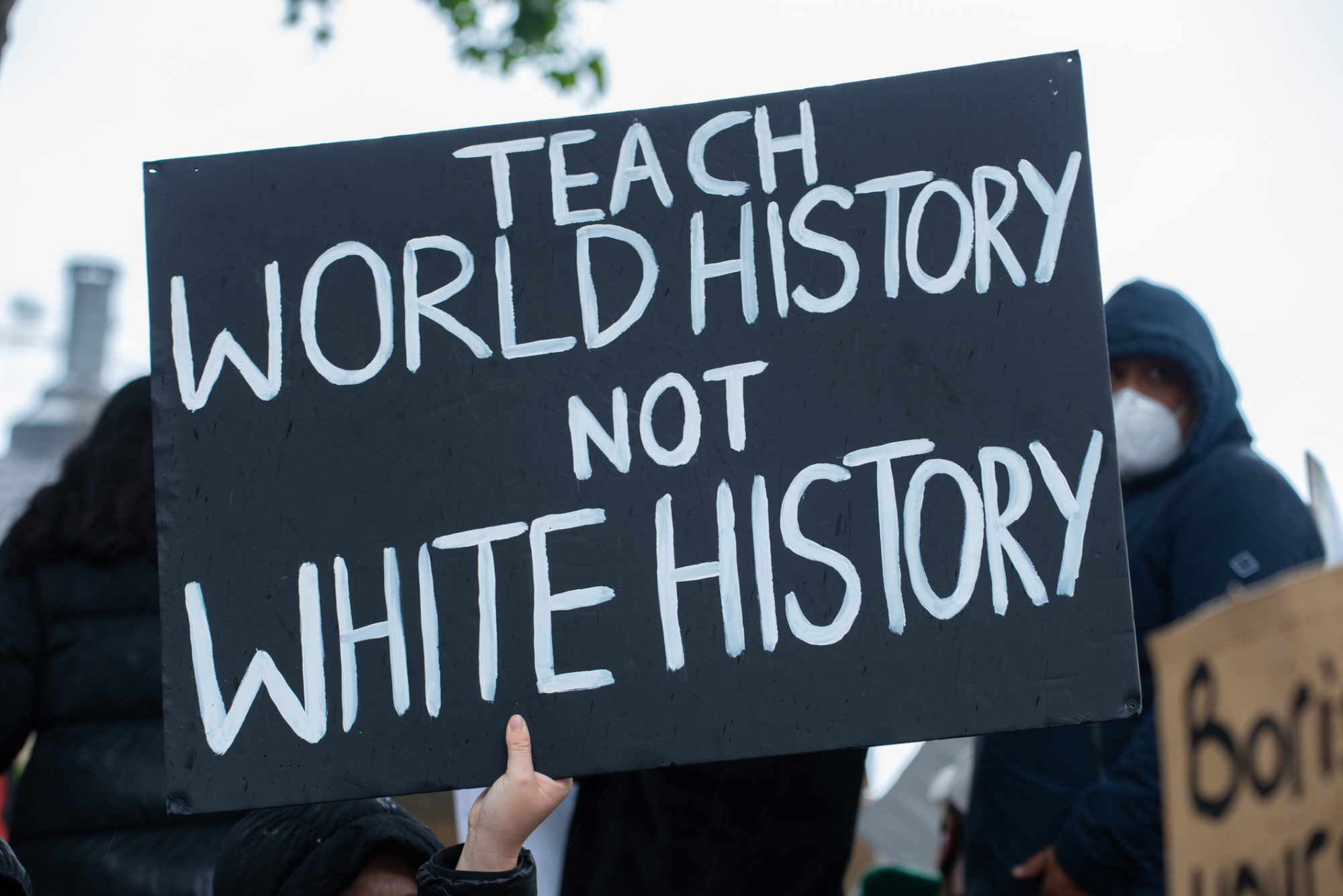

Black history in schools continues to be increasingly vital, as decolonising education and improving representation gives students a broader, more honest curriculum delving into systemic inequality

Another year celebrating Black History Month has gone by with many schools actively seeking to raise ways in which Black people have helped shape society. Young people will have participated in assemblies, events and lessons that bring the achievements of Black Britons to the forefront, and some may also have spent time thinking about why representation in the curriculum is important and how it can benefit everyone. A group of Facing History students wrote an article reflecting on Black History Month, and their thoughts on why diversifying the curriculum matters, with one student concluding:

“Finally, representation really matters; not tokenistic representation, but a true representation of voices, experiences and contributions in society.” Noor, Secondary school student.

However, despite Black History Month being a staple in the educational calendar for many years, a recent survey conducted by Censuswide for Facing History and Ourselves demonstrated that only 35% of young people feel they are being taught a representative version of history, and although 86% had heard of Martin Luther King, only 4% or less had heard of pioneering UK Black figures such as Paul Stephenson and Darcus Howe. This year’s Black History Month theme was ‘Time for Change: Action not Words’, and given these statistics, it is clear that more action is needed for the contribution of Black Britons to our history to be properly understood and recognised.

Only 35% of young people feel they are being taught a representative version of history

A call to action across British schools

Recently, former Children’s Laureate and writer, Malorie Blackman, made a call to action for English schools to embrace and teach a more holistic version of history – including that of the British Empire. Her voice joins many others in the public domain advocating for this change including David Olusoga, DJ Spoony, Stormzy, the National Education Union and Sathnam Sanghera.

Recognising and celebrating the contributions Black people – and those from other marginalised communities – have made to all aspects of society is an important part of diversifying the curriculum. Enriching our curriculum with the work of authors, poets and musicians from a wide range of ethnicities and cultures and learning about the achievements of scientists, medics, and members of the armed forces from marginalised backgrounds are just a few examples that help us to build a richer picture of our shared history.

From: https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk

However, this work is about more than celebrating these important contributions. It is also about facing the atrocities of the past. For example, it involves ensuring that our young people learn about Britain’s role in colonialism and the kidnapping, displacement and enslavement of over three million Africans. It means we can no longer ignore within our curriculum how this plunder and inhumanity has entwined British history with that of Africa and the Caribbean, and how the descendants of those who were enslaved and displaced are still affected by these acts.

Diversifying the curriculum does not mean rewriting history

Whilst there are many that advocate young people should be provided with a rounded and more complete version of our history, there are also those that are fearful of, or explicitly against such changes. They assert that we should not rewrite history and promote the idea that the positives of colonialism outweigh any negative impacts that it had. These arguments are not grounded in fact, however. Diversifying the curriculum does not mean rewriting history – it is exactly the opposite.

By diversifying the curriculum we write back into history the voices, stories and legacy of all of those who for so long have been whitewashed out of it. The commitment to giving young people this wider, more complete perspective is why teachers across the country are already doing the work to create more diverse and inclusive curricula for their students.

By diversifying the curriculum we write back into history the voices, stories and legacy of all of those who for so long have been whitewashed out of it

Studying a fuller version of history that incorporates the history of all marginalised communities across race, religion, gender and sexuality, disability and class benefit everyone. This would allow us to consider more thoughtfully and empathetically what makes people feel connected or unconnected to their learning, as well as provide opportunities to ask what Britishness and British identity means in a post-colonial society.

Turning the tide on history told through a predominantly male, white lens

Young people, regardless of their own ethnicity, will come to better understand the contributions and achievements of people from all backgrounds, and not just study history through a predominantly male, white lens. They will be able to come to a more nuanced understanding of systemic inequality and how society has been shaped by the legacy of colonialism. This deeper understanding of prejudice and oppression will generate greater empathy and connection to those who come from different cultures and backgrounds, helping to prevent entrenched, defensive or insular thinking.

This is particularly important at a time when those pushing hard right ideologies are finding ways to influence and enrol vulnerable young people in the promotion of their agenda of hatred, violence and division. The Director General of MI5 has warned that teenagers are at risk of being swept up in toxic discourse of ‘online extremists and echo chambers.’ Schools have a responsibility to ensure that their curriculum addresses this and enables students to have the tools to challenge such views. A diverse curriculum which represents British history is rich, and complicated, and is an intrinsic part of supporting this responsibility.

Yet, still, only 1% of students at the GCSE level study a book by a writer of colour and according to a YouGov survey from 2020, 30% of British people believe former colonies were better off as part of the British Empire. These statistics serve as stark reminders that more action is needed.

It’s time to move beyond words into action in education

Returning to Black History Month, some have long argued that the existence of a specified month for Black history not only prevents us from diversifying the curriculum but also reinforces a misconception that Black history is somehow different and separate from our collective history. However, If we are to really move beyond words into action and give all our young people an education which equips them for the future in a way that can eradicate racism and other prejudices and build a connected, empathetic society, we need to do the work of overhauling all curriculum so it is representative and told from many different perspectives.

There is help available online to build teacher confidence in navigating these vital conversations

It is hard work to do, and we will need a Black History Month for some time to come before we are truly in a position to say that the curriculum is diverse, inclusive, representative and one that our students want, and need.

Discussing complex and sensitive topics with students can be challenging, but there is help available online to build teacher confidence in navigating these vital conversations. Facing History and Ourselves UK, for example, has a variety of teaching resources, strategies and training to support educators in this, including lessons that engage students to consider historical and contemporary racism and antisemitism, and how to address prejudice in all its forms. Teachers can find our free resources here and sign up for online training and support here. We are also proud to be part of Diverse Educators, a collaborative community whose website and events offer a space to celebrate the successes and amplify the stories of a wide diversity of people, with blogs, reading lists, curriculum support, and resources.

This piece was written by Beki Martin, Executive Director of education charity Facing History and Ourselves