The MHINT-ERC project suggests that just because parents are the solution, does not mean they were the cause

Parenting is all too often implicitly or explicitly presented as the cause of child difficulties. Here, we argue that in order to harness the potential of parenting in preventing children’s mental health risk, we need to rethink, re-evaluate and re-articulate this causal assumption.

The role of parents in children’s emotional reactions are directly observable, both in everyday lives and experience. It is relatable, it is personal; we all have parents and feel the effects of how we perceive we are, or were, parented. Those of us who are parents must believe our often thankless and exhausting efforts mean something. There are thus emotional ties in believing that parenting is causal. It is embedded in history and at the core of most cultural beliefs and traditions.

Indeed, as the “problem” of juvenile delinquency was articulated and galvanised in the first half of the 19th century in Britain: “The improper conduct of parents was top of the list of principal causes: The first circumstances, which are allowed to operate in the formation character, flow from the exercise, or neglect, of parental authority and love.”1

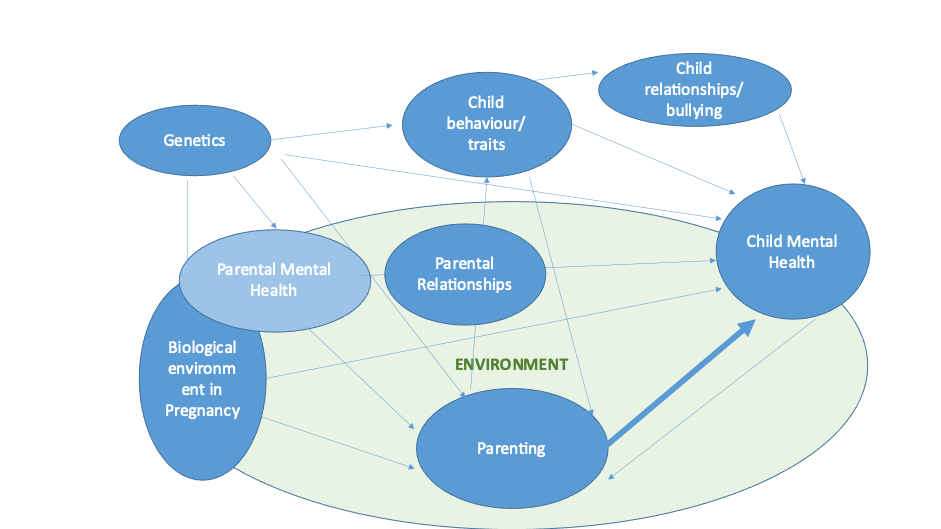

In addition to the inevitable muddying of the water from the emotional and historical pull, the science is complicated. While undisputable evidence links variation in parental response to child difficulties, when delving into potential mechanisms the connection is better described as a tangled web of often inseparable pathways. Parents and biological children are connected by genetics, in utero (for biological mother-children) and home environments. In the figure below, we represent some of these pathways, if only a direct path (in bold) is targeted, without considering the others we make little headway in preventing child or parental mental health risk.

A key argument in the pursuit of “causal” risk factors in translatable research is that if a link between an exposure and outcome variable isn’t causal then targeting such exposure would be, at worse, pointless and at best inefficient. Thus, should we be targeting parenting in interventions at all?

More concerning still, could they be doing harm? Parental confidence is strongly linked to child and parental mental health. The potential for “corrective” interventions, or a suggestion that an intervention is needed, seems likely to compromise parental confidence. We argue here to support parents in ways that let go of whether or not parents have a causal role.

To illustrate this point, let’s take the emotion out and consider examples in completely different areas of life (from medicine to football).

Scenario 1:

An individual feels fatigued. Their blood tests show they have low thyroxine levels. They are prescribed thyroxine, which brings their thyroxine levels to normal, they no longer feel tired. Here the intervention is directly linked to the cause (low levels of thyroxine), “fix” thyroid levels and the problematic symptom (fatigue) is prevented.

Scenario 2:

In another example, a footballer is unable to run following an injury after being fouled by a defender on the pitch. The intervention given to restore functioning is physiotherapy. Physiotherapists can’t prevent future injury on the football pitch by a foul from other players; however, physiotherapy can minimise the damage and rebuild strength.

Parenting will never be as simple as either of these examples, but Scenario 2 is less stigmatising. Building parents’ existing skills to flexibly adapt and support child behaviour when needed. Much like training a football coach in physiotherapy on the sidelines, ready to act quickly to manage injuries to prevent harm. Indeed no one would blame a physiotherapist for a foul-related injury, but they would be considered as the solution.

Parenting in the context of genetic risk

There is also evidence that mental health has a significant genetic contribution. As parents cannot change genetics, what does this mean for the concept of parenting interventions? A useful example in the age-old nature vs nurture debate is to see DNA as the recipe, environment as the ingredients, parents as the cook.

A recipe for a chocolate cake is not going to end up being a roast dinner, whatever the ingredients or cook, but the same recipe can result in a variety of chocolate cakes depending on ingredients, cooking equipment and who makes it. Parent “cooks” only work with the recipe given and resources they have. Within those parameters, however, they can protect from harm and nurture success.

Much like a cook keeping to the timings of a recipe, parents give structure when needed. We recently reported that emotional problems were higher in children post-pandemic than would be expected from pre-pandemic trajectories.

In a follow up, we have found that this risk was reduced when parents reported keeping a similar routine to before the pandemic. Parents here may act as a buffer, providing predictability in a context of uncertainty.

That said, however, much like a cook can do too much and “spoil the broth”, the same may be said for parenting. For example, a recent study links over certainty about child mental states to poor child outcomes2.

Perhaps the modern pursuit of perfect parenting and information overload is becoming counterproductive.

Where the “parents as the cook” example falls down is that children are not like passive ingredients which have no role in the way they are “cooked”.

Even from young ages, children “evoke” parental responses. Take a key example: more responsive parenting is reliably linked to “better” child outcomes. Thus, the extent of responsiveness by parents is often presented as a causal factor and targeted in many parenting interventions.

Let’s rethink this. A smiling baby is known to be one of the most reward activating stimuli. Fundamental understanding of behavioural learning models – where reward reinforces behaviour – would clearly predict that a baby who smiles every time a parent looks at them will evoke continued parental engagement.

Who has really “caused” the parental engagement, the parent or the child? Is it possible that the same factor that “causes” the baby to be more smiley causes them to be less likely to be depressed as they grow up? Will encouraging a parent to be responsive to a child who prefers to just be monitored help? We don’t yet know the answers to these questions.

What is next?

Re-evaluate

There are a large number of parenting interventions (from providing information/resources to hands-on coaching or video feedback) and many have been trialled. The evidence base for parenting programmes is mixed; findings from meta-analyses which pool the results of several studies to form a single effect estimate are consistent with both an improvement and no improvement in child mental health4.

However, standard methods to assess whether an intervention “works”, group interventions together as the same “treatment” and make a lumped comparison, for example, “all parenting programmes” vs control. This only answers the question “are parenting programmes in general effective?” and may mask important differences between parenting programmes which are multi-level.

In MHINT, we have thoroughly reviewed the literature and identified >50 randomised control trials with parenting interventions, which include early mental health outcomes in children3. We are using novel methods to break down these interventions (components-based network meta-analysis), allowing us to investigate which aspects of parenting interventions do and do not result in meaningful differences in later child mental health and which could be damaging, by also looking at parental mental health and parenting efficacy.

Rethink and re-articulate: Need for diversity in evidence base

Much of our understanding of behaviour is developed in “WEIRD” populations4, limiting the diversity of knowledge. MHINT is working with a number of international partners who are leading on innovative parenting projects, for example the BEACON study in South Africa is the first anywhere in the world to use wearable head cameras (developed by MHINT) to record parent-teen interactions.

This work will represent a true opportunity for African behaviour to inform development which is then translated to further populations, rather than the other way around.

Listening to lived experience of parents

In addition to providing parents with professional support through health, education or voluntary services, there are a growing number of parent to parent support programmes, such as Echo Peer Coaching – Beat (beateatingdisorders.org.uk).

Understanding the “who” as well as the “how” in what parenting support is delivered is a key part of the MHINT evidence synthesis protocol. Co-creation with those with lived experience can ensure the narratives and language used in discussing child mental health and engaging with parents is re-articulated to reduce stigma.

In order to understand what is helpful for parents, we need to listen to parents themselves. In MHINT we value the voices of those with lived experience, holding engagement events in community locations Who we are | We The Curious and we are currently inviting continued participation from those with lived experience.

References

- Report of the Committee for Investigating the Causes of the Alarming Increase of Juvenile Delinquency in the Metropolis London, 1816. pp. 10-12

- Jewell et al. (2021) Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01930-3

- Costantini, I. , Paul, E., Caldwell, D. M., López-López, J. A., &Pearson, R. M. (2020).. Systematic Reviews, 9, [244 (2020)] https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01500-9

- (WEIRD Populations/Unrepresentative Sampling | Science Exposed Are your findings ‘WEIRD’? (apa.org)

Contributors: Dr R Wallis, Dr M Cordero, Amy Campbell, PhD student, University of Bristol

MHINT ERC has received funding from the European Union’s HORIZON 2020 Research programme under the Grant Agreement no. 758813.

*Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.