Ambassador Aleksi Härkönen provides a compelling glimpse of the organisation’s efforts on climate change and pollution in the Arctic States

The Arctic Council is the leading intergovernmental forum promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the eight Arctic States – Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden, and the United States – in particular on issues of environmental protection and sustainable development in the Arctic. Indigenous peoples’ organisations have been granted Permanent Participant status in the Arctic Council, and have full consultation rights regarding the Council’s negotiations and decisions.

The Council celebrated its twenty-year anniversary on 19th September 2016. In that time, it has become a prime example of collaboration between the science and policy communities in global governance. With six Working Groups and two active Task Forces, and more than 90 distinct projects underway in areas as diverse as marine pollution, language preservation, Arctic economies, and climate change, the Council’s portfolio is extremely broad.

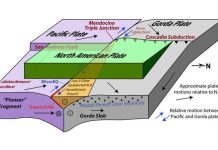

Among the most serious issues the Council presently addresses are pollution in the Arctic environment and climate change. The latter, in particular, is pertinent even well outside the Arctic region, as the Arctic is a critical component of the global climate system.

The Arctic Council has six Working Groups, which have produced – and which continue to produce – many of the most seminal scientific and analytical reports on matters of particular relevance to the Arctic region. These reports present the best available data and provide recommendations for action that are pertinent for the Arctic States, Arctic Council Working Groups, the Indigenous Permanent Participant organisations, or others.

In 2017, the Arctic Council’s Working Group AMAP published a policy-makers’ summary of their 2017 report “Snow, water, ice and permafrost in the Arctic”, or SWIPA. It finds that the Arctic’s climate is shifting to a new state, and that changes underway in the Arctic will continue through at least mid-century, due to warming already locked into the climate system. Warming trends will continue, as will declines in snow and permafrost. The melting of land-based ice will contribute significantly to sea-level rise, and the Arctic Ocean may be ice-free sooner than expected – possibly as early as the late 2030s. Indeed, while Arctic glaciers and ice caps represent only a quarter of the world’s land-ice area, meltwater from these sources accounts for 35% of the current global sea-level rise.

In addition, the 2017 SWIPA report finds that Arctic changes will affect both sources and sinks of important greenhouse gases, including atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane. The near-future Arctic will be a substantially different environment from that of today, and by the end of this century, Arctic warming may exceed thresholds for the stability of sea ice, the Greenland ice sheet, and possibly boreal forests.

Adapting to climate change

Beyond the challenges of climate change, the Arctic Council also recognises that resilience and adaptation to climate change are important for Arctic communities and ecosystems. The Council’s work on resilience can be seen in, for example, the 2017 Arctic Resilience Report and the project “Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic”. Increased activity in the Arctic (and elsewhere, as the Arctic is a sink for global pollutants) leads to an increased risk of pollution of many kinds in the Arctic environment. Some important pollutants – for example, persistent organic pollutants and mercury – have been addressed in various ways by the Arctic Council’s Working Groups for a long time. The Arctic Council’s work in this area has contributed to the work taking place under the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) Protocol on Persistent Organic Pollutants, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. But other pollutants are also gaining new relevance in the Arctic environment. These include oil pollution, marine litter (including microplastics), and chemicals of emerging concern in the region.

On oil pollution, perhaps the Council’s most important contribution has been to serve as a venue for the negotiation of a binding agreement among the eight Arctic States on preparedness for, and response to, oil pollution in Arctic waters (2013).

In addition, the Arctic Council conducted a Task Force on Oil Pollution Prevention from 2013-2015, which produced broad-based recommendations for avoiding oil pollution in the Arctic marine environment.

As to marine litter, the Arctic Council’s Working Group PAME is undertaking a desktop study on marine litter (including microplastics) in the Arctic. This may provide the first step towards developing a framework for a regional action plan on marine litter, although that is yet to be determined.

Chemicals

Finally, when it comes to chemicals of emerging concern in the Arctic, Working Group AMAP recently published a summary report that looks at a wide range of chemicals newly and recently detected in Arctic ecosystems. Changes to hydrology, declining sea ice, increased economic development, and changes in air and ocean currents – as well as changes in the way chemicals, distribute between air, water, and soils – are all consequences of a warming climate that are expected to alter how chemicals are released, transported to, and moved around in the Arctic.

These are but a few of many examples of research and analysis being undertaken within the Arctic Council Working Groups that directly supports the governments of the Arctic States, and others, as they tackle pollution in the Arctic and the adverse effects of climate change. But the Arctic does not exist in a vacuum; the Arctic climate, ecosystem, and economy are inseparably tied to the rest of the world. As changes in the Arctic have consequences elsewhere in the world, so changes elsewhere in the world can have enormous impacts in the Arctic.

In an age, and in a region, that faces such challenges, cooperation among the Arctic States, Arctic indigenous peoples, and other Arctic inhabitants is an absolute necessity to protect the Arctic environment and to support sustainable development in the region. But intra-regional cooperation alone will not be adequate to address the region’s challenges; cooperation on a global scale is essential.

Ambassador Aleksi Härkönen

Chair of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Officials