Professor Colin Suckling discusses the importance of chemistry…

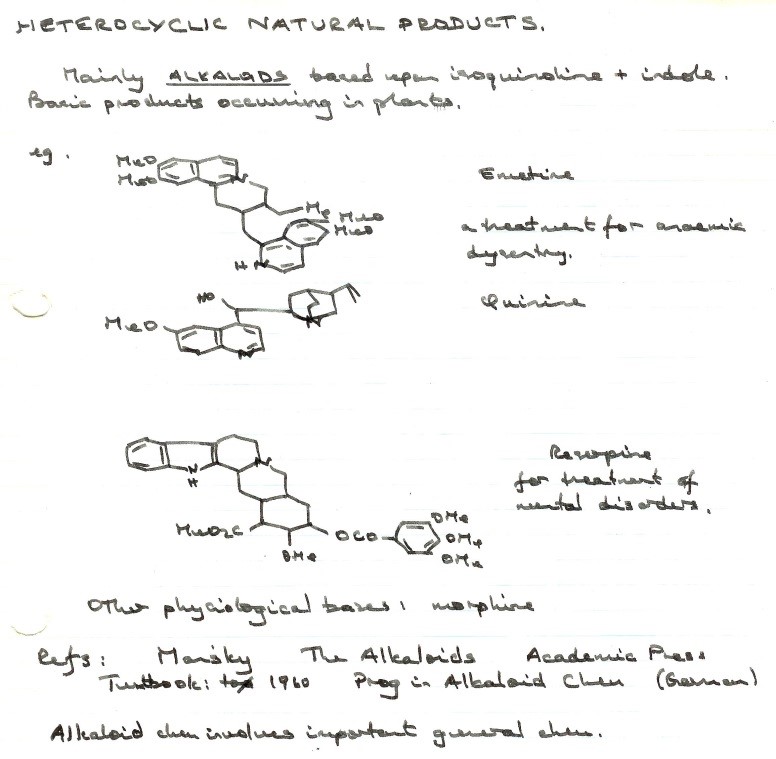

As the year moves on into August we in Universities start to prepare for the next academic year and beyond. Amongst the routine revisions that take place is the information for prospective students who will apply during the next academic year. I’ve just been reviewing Strathclyde’s brochure for our MChem in Chemistry with Drug Discovery, which I’ve not looked at closely for a few years because of a change in my responsibilities. Without going into any of the details it raised once again the old question, why study chemistry? Obviously being fascinated by the subject and doing well in chemistry studies at school are important considerations as they were when I was an undergraduate. The core components of the subject like thermodynamics, kinetics, functional group chemistry, and the chemistry of the elements are the same. I checked and looked at my old lecture notes, which I still have. For example, although now presented in a modern teaching environment instead of with chalk and blackboard, the basic material of heterocyclic chemistry that I learned would still be appropriate today.

But almost everything else has changed. Substantial fields of chemistry that commanded much interest and argument then no longer have a place in the curriculum. This is as it should be. One of the characteristics of the omitted material was that it was very inward looking. To put it another way, it was chemistry that interested the chemist but didn’t really do anything, or to use my favourite phrase from my old graduation speeches it didn’t ‘make things possible’. This encapsulates the major philosophical change that has taken place over the last half century in chemistry courses. Upon the same solid foundation of the core science as before, today we must show our students what we can do with chemistry, we must make connections for them with other conventional scientific disciplines, especially adjacent fields of biology, physics, and engineering. We must help them to become creative.

For my own students, some knowledge of biochemistry and pharmacology has been particularly important because of my field of research, medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. For some colleagues, it is spectroscopy and quantum physics that are important. The chemistry that we carry out in our laboratories produces new compounds and new materials that make a difference and make things possible for others. This echoes Berthellot’s famous remark that ‘chemistry creates its own object’; so much the better if that object has properties of practical value like a new drug or new light-emitting material, as I have discussed in previous Special Reports.

Outputs of practical use are one thing. Another, arguably more important, is the range of skills that a good chemistry curriculum provides, analytical, conceptual, practical, mathematical, and many more. Add this to the range of knowledge and connections with other fields as I have mentioned and the value of a chemistry degree stands out. I’m sure that one reason why many of my later PhD students found no problem in getting jobs was their comfort in interdisciplinary science together with their practical skills and underlying chemical competence. Graduates with a good chemistry degree are valuable, versatile people.

It’s arguable whether modern studies of particle physics will directly affect our daily lives. Perhaps they will and I think it’s good to know more about the fundamental properties of matter anyway. Simply understanding more subtle details about biology won’t on its own make something useful happen although it can make an opportunity. We need that key translational component, chemistry, the science that can create the objects in the form of new molecules that make the difference. What other science has room for discovery, creativity, and applicability?