Previously thought to be defined by simple cloud patterns, NASA’s JWST has unveiled the astonishing complexity of SIMP 0136, a starless super-Jupiter

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has revealed a surprisingly intricate and dynamic atmosphere surrounding SIMP 0136, a free-floating planetary-mass object, challenging previous assumptions about the nature of such celestial bodies.

An international team of researchers, leveraging Webb’s unparalleled infrared sensitivity, discovered that the object’s fluctuating brightness is not solely attributable to cloud cover, but rather a complex interplay of varying cloud layers, temperature fluctuations, and changing carbon chemistry. This groundbreaking research offers a crucial glimpse into the three-dimensional complexity of gas giant atmospheres, both within and beyond our solar system, and paves the way for future exoplanet exploration.

Rapidly rotating, free-floating wonder

SIMP 0136, located a mere 20 light-years from Earth, is a unique object, approximately 13 times the mass of Jupiter. Although not classified as an exoplanet due to its lack of a host star, its isolated nature and rapid 2.4-hour rotation make it an ideal target for detailed atmospheric studies.

As the brightest object of its kind in the northern sky, it allows researchers to gather data without the interference of stellar light. Prior to Webb, the object had been studied by ground-based observatories, as well as Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes, revealing brightness variations indicative of patchy cloud cover. However, the true complexity of its atmosphere remained hidden.

“We already knew that it varies in brightness, and we were confident that there are patchy cloud layers that rotate in and out of view and evolve over time,” explained Allison McCarthy, doctoral student at Boston University and lead author of the study.

“We also thought there could be temperature variations, chemical reactions, and possibly some effects of auroral activity affecting the brightness, but we weren’t sure.” Webb’s ability to capture precise brightness changes across a broad range of infrared wavelengths was essential to unravelling these mysteries.

Charting thousands of infrared rainbows

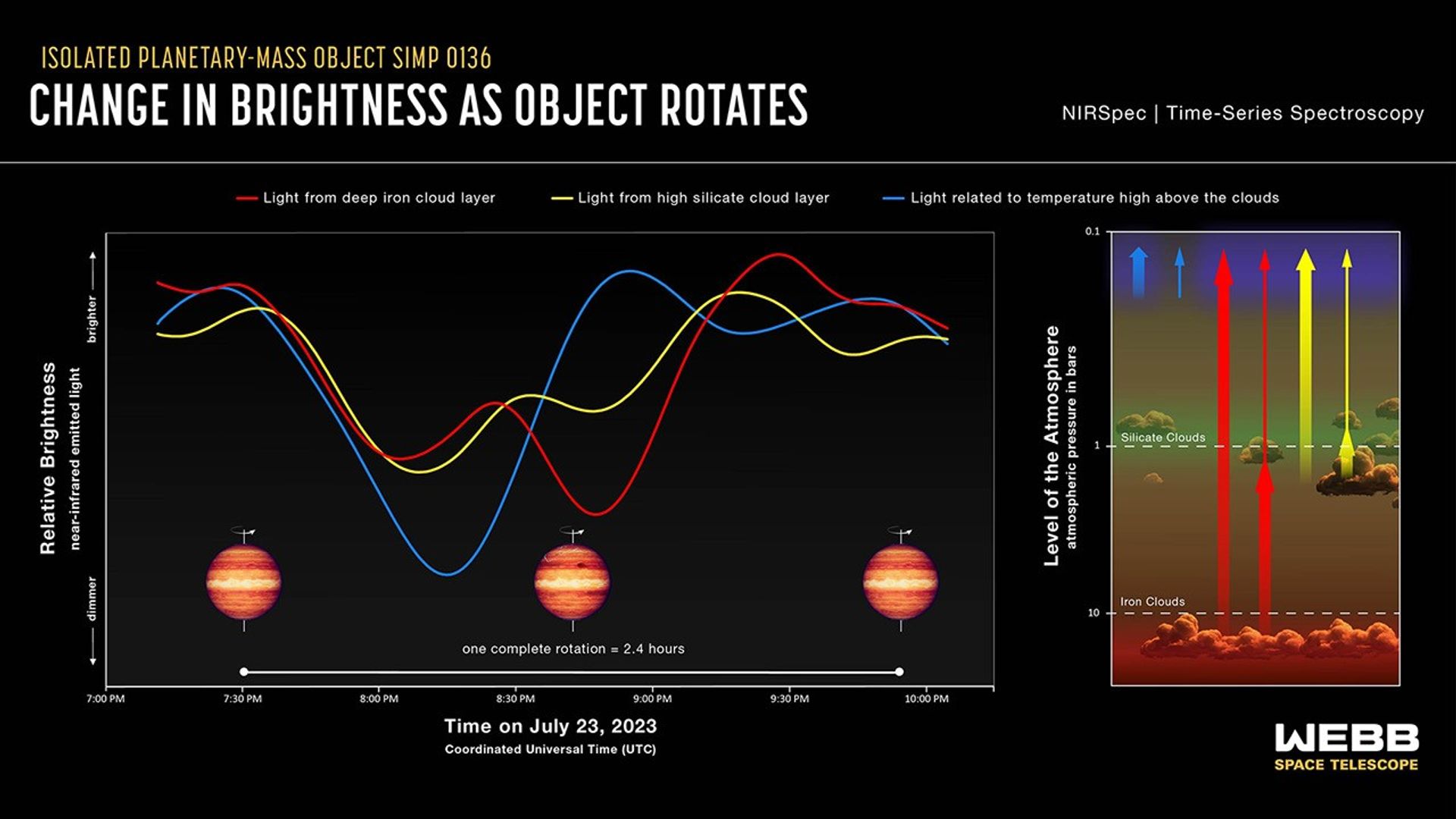

The JWST’s observations utilised the NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) to capture thousands of individual spectra, effectively creating detailed light curves. NIRSpec collected data over a full rotation, followed by MIRI observing a second rotation. This resulted in hundreds of light curves, each depicting the brightness variation of a specific wavelength as SIMP 0136 rotated.

“To see the full spectrum of this object change over the course of minutes was incredible,” said principal investigator Johanna Vos, from Trinity College Dublin. The team immediately noticed distinct light-curve shapes, with some wavelengths brightening, others dimming, and some remaining relatively constant, indicating a multitude of interacting factors.

“Imagine watching Earth from far away. If you were to look at each colour separately, you would see different patterns that tell you something about its surface and atmosphere, even if you couldn’t make out the individual features,” explained co-author Philip Muirhead, also from Boston University.

This concept helped them interpret the complex data from SIMP 0136.

Image: © NASA, ESA, CSA, and Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

Patchy clouds, hot spots, and carbon chemistry

To understand the causes of these variations, the team used atmospheric models to determine the origin depth of each wavelength. They discovered that wavelengths with similar light-curve shapes originated from similar atmospheric depths, suggesting a common mechanism.

One group of wavelengths pointed to deep atmospheric layers with patchy iron particle clouds. Another group indicated higher altitude clouds composed of silicate minerals. Both showed variations related to cloud patchiness. A third group, originating from high altitudes, revealed temperature fluctuations, possibly linked to auroras or upwelling hot gas.

Intriguingly, some light curves couldn’t be explained by clouds or temperature alone, suggesting variations in atmospheric carbon chemistry. This implies fluctuating pockets of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide or ongoing chemical reactions. “We haven’t really figured out the chemistry part of the puzzle yet,” said Vos. “But these results are really exciting because they are showing us that the abundances of molecules like methane and carbon dioxide could change from place to place and over time.”

This discovery has significant implications for exoplanet studies. If similar atmospheric complexities exist in exoplanets, single-point measurements might not accurately represent the entire planet. The detailed characterisation of objects like SIMP 0136, facilitated by Webb, is crucial for preparing for future exoplanet imaging missions like NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

This research underscores the power of Webb in revealing the hidden complexities of celestial objects, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of planetary atmospheres.