CEO Kaddu Sebunya and David Williams of the African Wildlife Foundation, explain the harnessing technological advances to improve conservation management in Africa

Africa’s conservation lands–protected areas and private conservancies–face significant and accelerating threats. Expanding foreign direct investment targeting natural resource extraction and a burgeoning human population that is expected to double to two billion by 2050 have increased pressures to convert conservation lands to other uses such as agriculture and mining.

In addition, sophisticated, well-armed poaching syndicates decimate wildlife populations to meet a surge in demand for wildlife products ranging from ivory and rhino horn to pangolin scales and lion bone. These three-pronged challenges have led to rapidly declining biodiversity across the continent and the world over, as evidenced by a recent United Nations report that stated that one million species are at danger of extinction, many of them in the next few decades.

It is against this backdrop that managers charged with protecting conservation lands operate. They usually have a small, under-resourced ranger force and are charged with protecting vast, often inaccessible territory. Worse, their ‘situational awareness’ –current knowledge of wildlife and threat locations and movements–across these expanses is limited or dated hampering decisions on where and when to direct their rangers and other management assets.

However, recent technological advances have played a major role by contributing new eyes to monitor threats to wildlife and their habitats, therefore improving situational awareness and helping managers maximise use of their rangers. Here I present an example from African Wildlife Foundation’s (AWF) work in Central Africa.

Bili Mbomu

Only 25 rangers protect the 11,000 km2 Bili Mbomu section of the Bili-Uélé protected area complex in remote northern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). While dedicated, the force is 61 times smaller than the International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN recommended size leaving Africa’s largest population of eastern chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) and significant elephant (Loxodonta sps.) and lion (Panthera leo) vulnerable. Up until 2015, Bili Mbomu was a ‘paper park’ with no rangers in a lawless frontier and subject to exploitation from mining, logging and the infamous Lord’s Resistance Army seeking ivory to fund its operations and arms purchases.

When the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN), the government institution tasked with protecting DRC’s wildlife, set up in Bili, the warden, or, conservateur, had little idea of the distribution of wildlife and threats in the region.

Filling the knowledge gaps

AWF stepped in and trained and equipped ICCN rangers to use ruggedised smartphones equipped with an app called CyberTracker. With a few clicks, rangers record the presence of wildlife such as elephant dung as well as evidence of threats—hunting camps, cartridges and snares (or poachers themselves). Back at the field station, onsite data managers download the CyberTracker patrol data into a patrol data management software, SMART (Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool), that with a click can produce reports replete with maps of wildlife and threats, graphs of trends in snares encountered and tables measuring how hard each ranger is working. The conservateur then uses the reports to inform his patrol planning. It is proof of the landscape’s vastness that even after a year of patrols, the small ranger force has not visited huge expanses of Bili Mbomu. Yet, declining poaching numbers in that part of the landscape is proof that our model works.

Predicting threats and wildlife hotspots

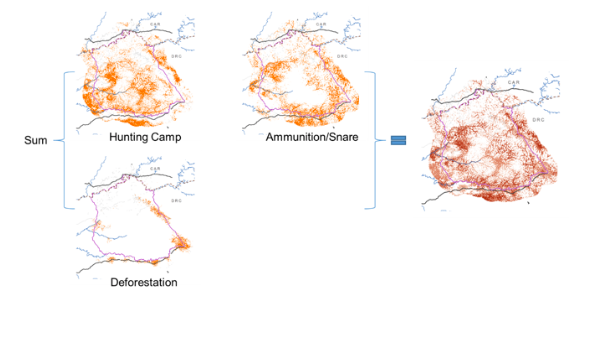

AWF leverages the increasingly rich data available from Bili Mbomu patrol observations and satellite imagery to drive machine learning-based spatial models that predict the distribution of wildlife and threats across the landscape. The team generates models of key wildlife species, ammunition and snares and hunting camps driven by patrol observations, as well as data about habitat loss from deforestation generated by satellite observations. We then sum up the individual models into wildlife and threat indices to enable identification of wildlife and threat hotspots (e.g., Figure 1).

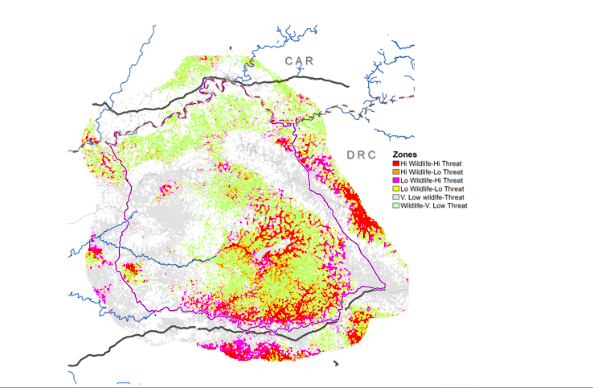

Validation of these models using independent data has bolstered confidence in their utility for improving situational awareness. Armed with this data, the conservatuer has adopted a strategy focusing on the southeastern sector where the wildlife and threat hotspots overlapped, but which only represents a small fraction of the vast landscape (Figure 2). We credit a combination of evidence-based decision-making and old-fashioned patrol sweat with declining trends of hunting camps and preliminary signs of wildlife population recovery in the landscape over the past three years.

With high-frequency patrol and satellite data streams, this 21st-century conservation toolkit can closely track wildlife-threat dynamics and cater to more agile and responsive management. AWF has replicated this platform at five other sites in DRC and Cameroon and has plans for further application.

Trial and share

As technology advances, conservationists should be aggressive in exploring and adapting new tools with specific application objectives that fit into a broader conservation programme and then share findings with the conservation community. An explosion of satellites, especially constellations of ‘small sats’ launched in recent years will further enrich the situational awareness picture with unprecedented ability to capture high-frequency snapshots of events such as forest loss, road construction and settlement development that mark conversion of wildlife habitat. Cloud-based processing tools are emerging to automatically extract such features from the imagery.

On the ground, a next-generation network of sensors will feed real-time dashboard displays about wildlife movements and potential threats such as vehicle encroachment. Can conservationists harness the potential of these exciting tools to turn back the assault on conservation lands? We owe it to Africa’s wildlife and the world, to try.