The race to net-zero carbon and a green recovery is on, and here, Prof. Dr. Raimund Bleischwitz explains how this will require systems thinking

While the COVID-19 pandemic still requires attention and care, the quest for a green recovery is on. Hardly any citizen wishes to return to the old normality with long commutes, air pollution and looming climate change risks. Rather, many people wish to press a restart button able to catapult societies into a future of reclaimed urban spaces, clean technology, and net-zero carbon. Activities are in fact impressive; the Race to Zero Initiative claims to have obtained zero-emission pledges from 450 cities, 505 universities (including UCL) and more than a thousand businesses covering 53% of the global economy and roughly one-quarter of global emissions. This indicates the tremendous power and influence of ‘non-state actors’, be it investors, regional governments, small and large businesses and universities.

COP26 and a green recovery

The next UN climate change conference, dubbed as COP26, is likely to become a landmark bringing together main state actors on nationally determined commitments and non-state actors alike. Shifted from late 2020 to November 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland, it is now a window of opportunities to refresh ambitions and deliver. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the main host of COP26, calls for a ‘whole systems approach’ to decarbonisation efforts.

In line with the new EU €750 billion recovery plan that is geared towards green and digital transformations and with the new EU’s sustainable finance taxonomy, such approach should be broader than climate action; the road to COP26 should be driven by a green recovery agenda including water, air pollution and biodiversity. Transformative action may focus on one area without harming others, or address issues in a more integrated manner.

A new mission includes a circular economy

A new mission to zero emissions is needed – beyond the Paris Agreement and the SDGs. A new mission will have elements of a long-term vision for a sustainable society. In line with Mariana Mazzucato, it can be expected to inspire mission-oriented policies and changes in business models. A more circular economy should be a cornerstone. A circular economy is designing out waste and emissions by maximising utility over time and maintaining values. It is a positive mission with pledges from various companies, including BlackRock, Google, and Unilever, and from governments worldwide.

A new mission, however, is a mere starting point to encourage thinking outside-the-box. It needs to be bolstered by transformative strategies based on ambitions, evidence, and ongoing research. The energy transition offers useful insights into how core regimes have started to change fundamentally. Denmark-based renewable energy provider Orsted has just been ranked as the most sustainable company world-wide in 2020, after they revamped their business model away from fossil fuels. Italian-based ENEL is running the crowdsourcing platform Open Innovability with the intention to create and deliver radically innovative solutions to grand challenges. The energy transition continues despite a minor backlash during the pandemic, as renewable energy has become the least-cost option in the power sector. The next challenge is a transformation of heating/cooling, transportation, and the foundation industries.

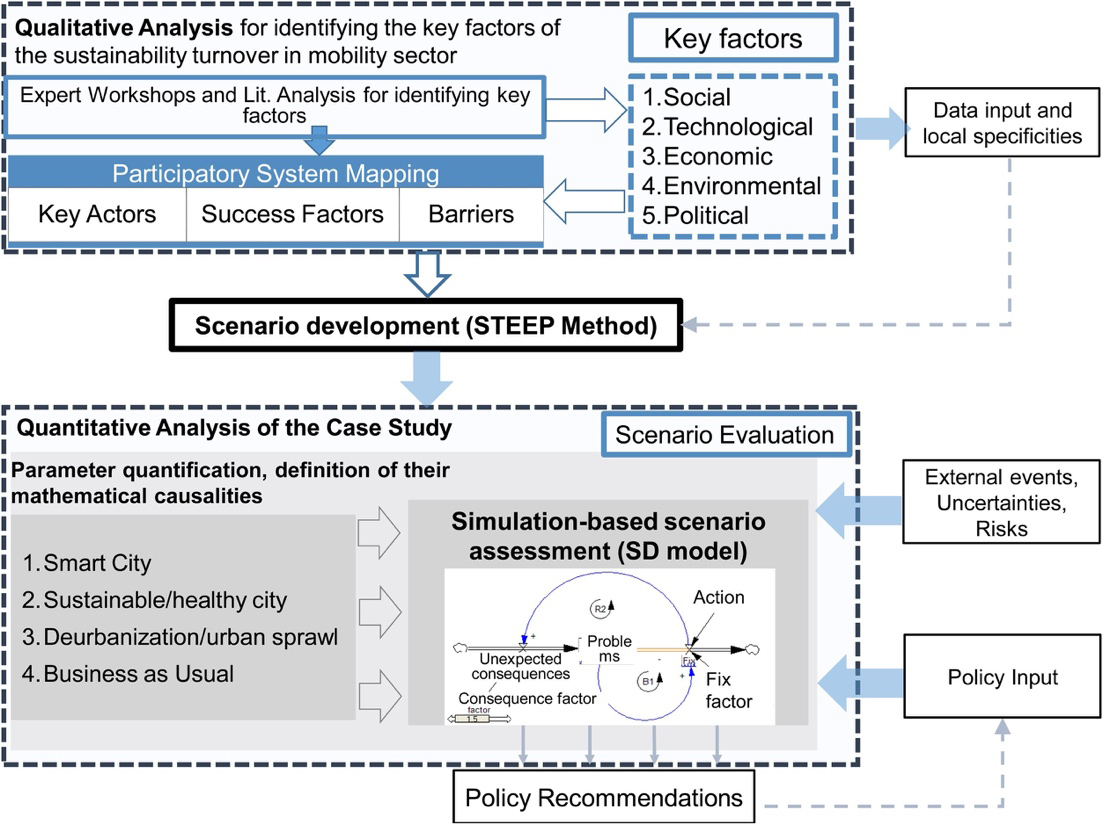

Designing a new urban mobility with participatory methods and modelling

With a view to commuters, transforming urban mobility will be essential. Take the Rhine Ruhr metropolitan region in Germany, for instance. Recent research demonstrates how it could become net-zero in 2030 if public infrastructure investments in e.g. biking lanes could be increased from today’s €1,000 per capita and annum up to €4,000. As usual, finding evidence on the willingness to embark on such a journey and its feasibility requires robust methods and should include a new mission: this research looked holistically into a diversity of visions of a smart city, a healthy city, and deurbanisation; using a participatory approach with a range of stakeholders to develop scenarios, it applied a system dynamics model and tested it against a net present value framework for governmental investments. Similar work is underway in the UCL project on Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (CUSSH) and our urban mobility lab (Maaslab). If cities reduce the number of cars and with them the need for parking, some 10% extra space will become available to plant trees, and creating green urban areas.

Foundation industries delivering sustainable materials for smart societies

Materials such as steel and cement are vital to modern society, but their production is an important source of greenhouse gases and environmental pressures. Emissions from material production are now comparable to those from agriculture, forestry, and land use change combined; base metals are estimated to be as environmentally intensive as fossil fuels. According to UNEP’s International Resource Panel, GHG emissions from the material cycle of residential buildings in the G7 and China could be reduced by at least 80% in 2050 through design with less and better materials, re-use of construction materials, and other strategies. In the aftermath of the pandemic, a more intensive use of homes and a transformation of the built environment for office space is on the agenda. In a vision, a full metal circulation is on the horizon. Recent macro-economic findings indicate an acceleration in the re-use of steel over the next years is likely to benefit the economy of main producing countries, including China, and the majority of developing countries. Our research indicates a growing awareness among industry and a willingness to engage in international performance indicators measuring embodied emissions.

Learning from the pandemic: enabling systemic triggers

Societies have been learning useful lessons in complex systems over the last months. Clarity about social norms and desirability of international cooperation has become more widely acknowledged. It is time to look beyond individual energy efficiency measures and to reduce global footprints of carbon, materials, water, and land via systemic eco-innovation. Such activities create interconnected networks of ‘super spreaders’ for sustainability holding the purse strings. To phase out fossil fuels and re-distribute remaining fossil fuel production towards developing countries based on equity considerations, lessons from anti-contagion policies could be deployed. By applying lessons from systems thinking we can finally scale-up efforts through networks, policies, and new economic thinking to tackle the crisis we face with the urgency it demands.

Please note: This is a commercial profile