Having lifted most of its COVID regulations – spikes in infections show that UK herd immunity through vaccination programmes is not efficient in the long run

It is plausible that the Coronavirus is not going to depart from our lives any time soon, but ‘living with the virus’ – as seen with the UK herd immunity strategy in its lack of COVID regulation – carries its negative attributes throughout the country as spikes in infections, and deaths, continue.

What does herd immunity mean?

“Herd immunity” is the notion of allowing the population to endure the virus to develop protection against a disease through immune responses in the body.

What the UK herd immunity strategy is currently based on, is the implementation of vaccination programmes, as well as letting people to catch the disease to build up their immunity. If exposed to the virus again, it has been assumed that people have protection against severe illness through existing antibodies.

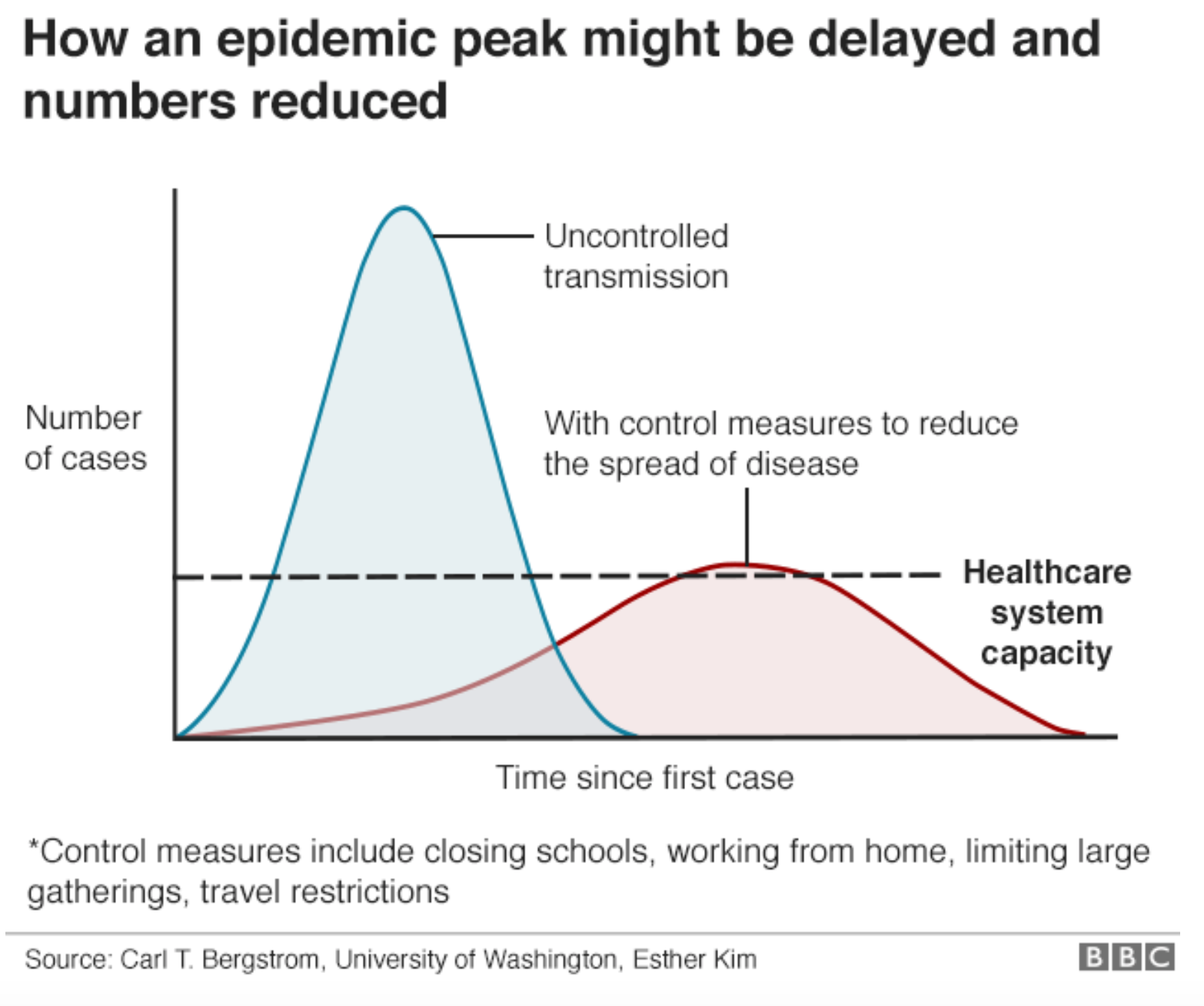

The concept of herd immunity proposes that if most people in the population are protected through vaccination or naturally-occurring antibodies, then the virus cannot spread.

“When the Government moved from the ‘contain’ stage to the ‘delay’ stage, that approach involved trying to manage the spread of Covid through the population rather than to stop it spreading altogether.”

As of January 2022, England saw its highest ever spike in infections and hospitalisations, with over 820,000 new cases on January 31st. Two months following this, England dropped all COVID regulations and restrictions, relying predominantly on a vaccination programme to carry out the safety measures against the deadly virus.

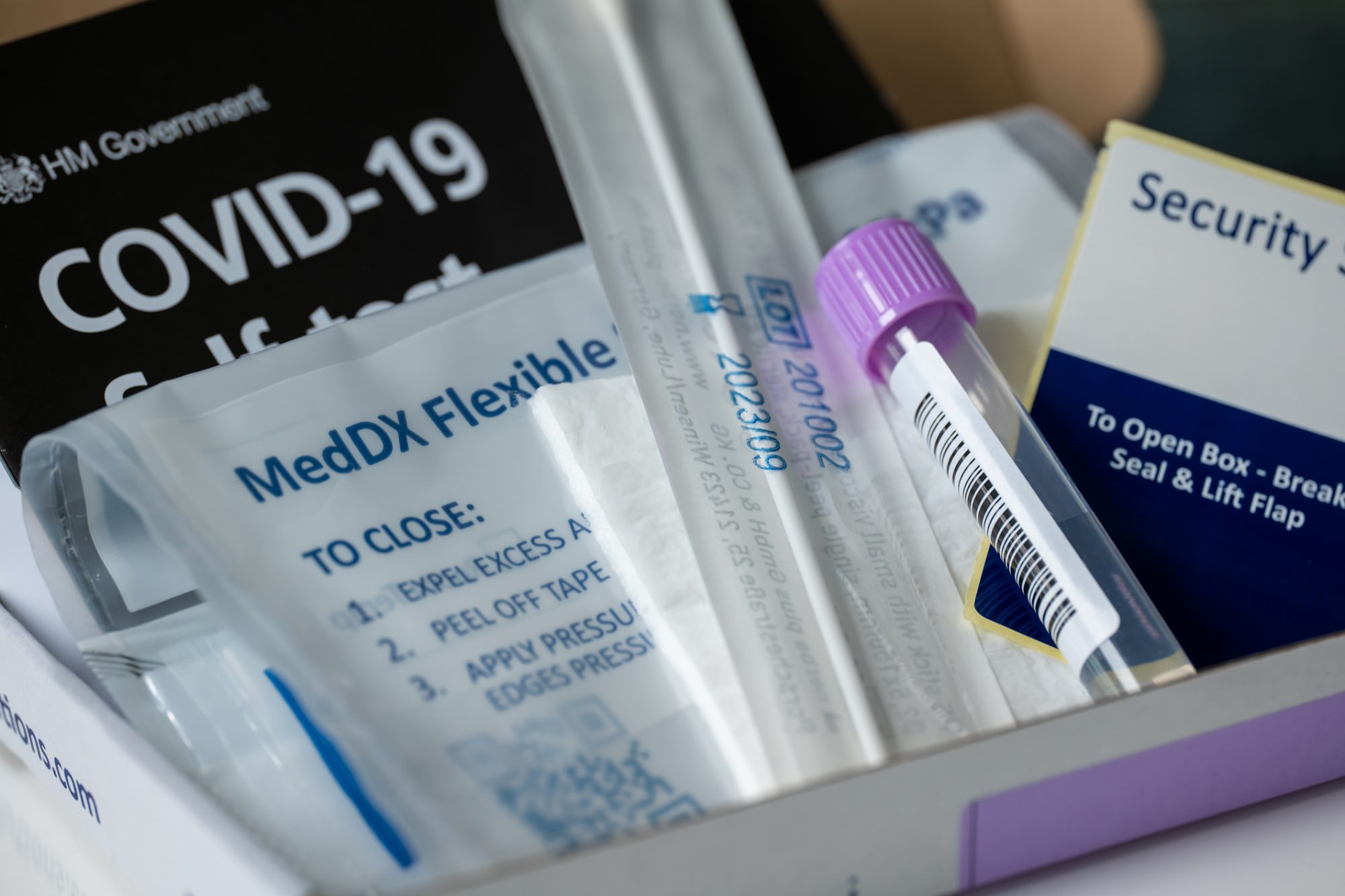

When COVID restrictions – including isolation rules and mask requirements – began to differ across the UK, England scrapped the need to self-isolate and phased out access to free COVID-testing products from April 1, 2022. In other parts of the UK, officials in Scotland and Wales also began lifting restrictions, despite COVID cases increasing.

https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk

So, is UK herd immunity working? Or are we setting ourselves up for the fallout to come with the next variant?

Omicron, XE, and other COVID variants

The UK has seen the large spread of four variants so far – Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron.

Predicted to battle another by summer of 2022, the XE variant – a sub-variant of Omicron, estimated to be 10% more infectious than the other variants thus far – continues to rise across the country. Yet, little information has emerged to explain the threat XE potentially poses, because the UK has stopped multiple forms of observing the virus.

Variants are essentially carbon copies of viruses to reproduce, where genetic blueprints are ‘edited’ through transmission – resulting in a new version of the virus. If this gives the virus a survival advantage, the new version will also begin to spread through people.

These variant mutations are made through infection, which can be prevented by vaccination. However, mutations can still occur when the population is vaccinated too.

It was predicted in 2020 that around 60% of the population would need to become infected for society to have “herd immunity” – which is almost 40 million people. With well over 20,000 people on hospital ventilators for COVID across the country today (14 April), UK herd immunity has not been enough to stop variants from forming and attacking people, even when vaccinated.

Herd immunity allows for people who are infectious to spread COVID-19 and mutate the virus through transmission. Despite vaccines lessening death rates, vaccines will need to continue to be generated to tackle every deadly variant to arise from COVID in the future.

COVID vaccines, though vital, lose efficacy over time

There are problems which arise from UK herd immunity. Firstly, with coronavirus, researchers are still mostly unclear as to how much protection the disease gives you once you’ve had it, or how long this immunity can last.

Additionally, vaccines developed do not last forever – effectiveness does begin to diminish over time.

Relying on the vaccination programme, the UK government scrapped most COVID regulations because of the success of the vaccines against the virus.

Granted, policy decisions have taken daily COVID deaths down from 38,000 to 127 between January to July of 2021, but researchers find that booster jabs are going to be needed as a top-up for prolonged immunity.

“Breakthrough cases” or “breakthrough deaths” – where infection, and potentially death, has occurred in someone who is fully vaccinated – still occurred during and after the vaccination period. Overall, there were 256 breakthrough deaths between 2 January and 2 July 2021. This demonstrates that vaccines alone cannot contain the virus.

Though vaccines are the most efficient way of protecting people against the virus, herd immunity still allows for newer variants to arise and surpass some vaccinated people. Vaccination also does not prevent infection, but rather, it lessens the symptoms.

The long-term health implications of the Coronavirus are still mostly unknown, so just relying on the vaccines for long term protection is not ideal for health or safety during a pandemic. Masks, social distancing, cleanliness, and free testing should continue to see the best outcome of the vaccination programmes.

Minority ethnic groups suffer the most from COVID-19

UK herd immunity essentially allows the most vulnerable people, especially those who do not know they are vulnerable, to fall through the cracks of the healthcare system. Of which, minority ethnic populations across England suffer the most.

“We know that some ethnic minority groups continue to suffer worse outcomes from COVID-19, seeing higher rates of infection, hospitalisation and death”

Vulnerable people can account for the known 170,000+ deaths that the UK has seen thus far. Within this population, the mortality rate for deaths involving COVID-19 was highest among males of Black ethnic background – at 255.7 deaths per 100,000 population. Deaths were lowest among males of White ethnic background, at 87.0 deaths per 100,000. Similar death rates were also seen amongst Black women, which were at a higher rate than white women.

From even before vaccination, across all ages in the UK in 2020, the rate of deaths involving COVID-19 for Black males was 3.3 times greater than that for White males of the same age, while the rate for Black females was 2.4 times greater than for White females.

Additionally, among men from Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Indian ethnic backgrounds, there was a much higher risk of death involving COVID-19, at 1.5 and 1.6 times, than white men. This statistic remained after taking into account what region, population density, socio-demographic and household characteristics occurred in patients.

It has also been shown that non-English speaking patients with COVID in hospitals have a 35% higher chance of death, due to lack of communication and potential lack of immunity due to being of a different racial background.

The UKHSA said: “We know that some ethnic minority groups continue to suffer worse outcomes from COVID-19, seeing higher rates of infection, hospitalisation and death. If more people from these communities take part, we can understand why this is happening and respond to it better.”

While access to ventilators and the NHS can navigate through the worst cases of the virus, hospitals have been threatened by overpopulation and lack of resources – and now, with herd immunity – staff too.

Dropping all COVID restrictions does not mean that people are not threatened by the virus anymore. If anything, it has become a bigger threat because people with COVID are less likely to know if they have it, subsequently pass it on, and give it to vulnerable people.

How do we protect the British public without subjecting them to complete COVID vulnerability?

Though the virus has not gone away, the UK public will have to learn to live with it.

However, the virus can be lessened through efficient COVID regulations and safety measures – as we once saw when in lockdown. UK herd immunity and dropping all COVID restrictions is not the answer.

Masks and efficient ventilation should be encouraged everywhere, as well as continuation of the vaccine programmes. Most importantly, free testing kits should not be scrapped and PCR testing should remain intact to protect vulnerable populations and stop the virus from spreading to mutate and potentially become more dangerous.

A report by British Lawmakers said: “When the Government moved from the ‘contain’ stage to the ‘delay’ stage, that approach involved trying to manage the spread of Covid through the population rather than to stop it spreading altogether.

“This amounted in practice to accepting that herd immunity by infection was the inevitable outcome, given that the United Kingdom had no firm prospect of a vaccine, limited testing capacity and there was a widespread view that the public would not accept a lockdown for a significant period.”

We cannot avoid COVID deaths and long-term health risks by pretending it is simply not happening.