Warwick Business School’s Professor Stephen Roper reveals the UK Government’s exciting plans for funding research and development in business

Historically, the UK has under-invested in research and innovation compared to its leading international competitors. This may be about to change, however, at least as far as public support for research and innovation is concerned.

The UK Government’s Industrial Strategy Green Paper published this spring contained an eye-catching promise, to increase public spending on supporting R&D and innovation by around €2.2bn per annum by 2021. This amounts to increasing public support for business R&D and innovation in the UK by around two-thirds over the next four years. How (and where) should this new spending be allocated? Should we invest in basic R&D which may lead to commercial benefits in many years’ time? Or, are we better investing in more applied R&D which is closer to market, and which may do more in the short-term to address the UK’s productivity challenges?

Individual scientists and innovators in the UK will have their own priorities, of course, and there is probably a good case to be made for more investment in many areas of scientific and innovation activity. But what does the evidence say? And, what can we say about where the returns from investment are greatest?

New data

A new study recently published by the UK Enterprise Research Centre provides at least some of the answers. This study, the first comprehensive assessment of the business benefits of grants from the Research Councils and Innovate UK, examined the impact on business growth and productivity of all Research Council and Innovate UK grants for research and innovation provided between 2004 and 2016. It looked at around 10,000 companies which participated in publicly funded research or innovation projects over this period and compared their performance to a closely matched control group drawn from the one million or so other UK businesses (with employees).

The findings are encouraging. Firms which participated in publicly funded projects – and these were primarily funded by EPSRC and InnovateUK – grew their turnover and employment 5.8-6.0% faster in the three years after the project, and 22.5-28.0% faster in the six years after the project, than similar non-participating firms. There were also productivity gains of around 6% over six years.

Increased spending

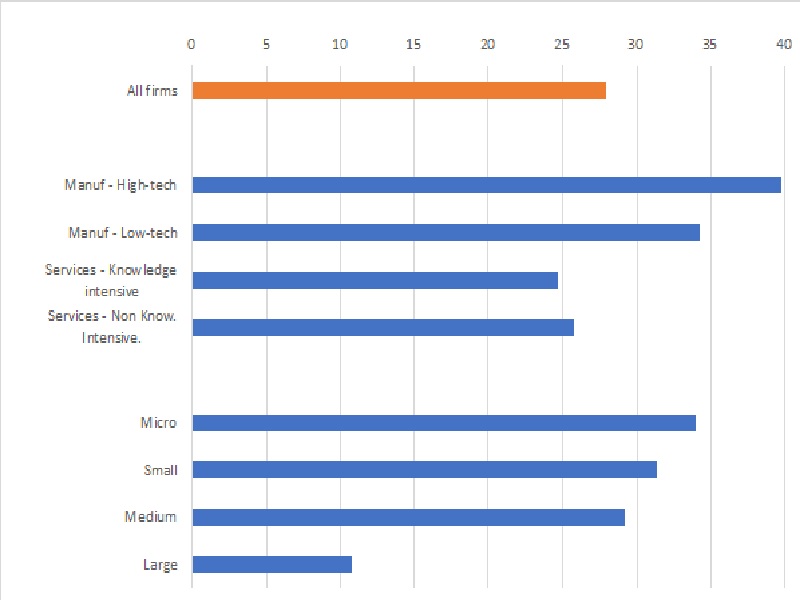

Figure 1: Turnover growth impact of participating in publicly funded science, research and innovation projects after 6 years (%)

So, the UK might anticipate significant positive benefits from the new Challenge Fund spending. Patience will be necessary, however. Challenge Fund investments in 2018 -2020 will not have their greatest effects on business performance until 2024- 2026. Whether this is before or after post-Brexit trade deals are concluded between the UK and other countries remains to be seen, but investments such as the Challenge Fund will contribute to the future international competitiveness of UK firms.

The new research also provides an indication of what types of firms benefit most from participating in publicly funded science, research and innovation projects. Figure 1 illustrates this in terms of the impact on turnover growth over the six-year period following the start of the project. For all firms (the top bar) being part of a project adds 28% to turnover growth. This effect is larger for manufacturing firms, particularly in high-tech industries. It is also larger where firms are smaller. Larger firms benefit less in proportional terms.

Plausible explanations for these results relate to larger firms’ stronger financial resources and the higher cost of manufacturing v service sector innovation. For those seeking to maximise the returns to future Challenge Fund investments, however, the messages are clear: think smaller firms, think high-tech manufacturing.

Looking forward there is significant anxiety within the UK research and innovation community about the effects of Brexit. The extent to which leaving the EU will undermine existing research networks, reduce available funding and make the UK a less attractive place to do science remains uncertain despite reassuring noises from politicians. This is not just a funding question. Restrictions on researcher mobility – and a perceived climate of hostility – also have the potential to reduce the flow of scientific talent to the UK.

In ‘normal’ times, the boost to public support for research and innovation which the Challenge Fund represents would be a significant boost for UK innovation. The anticipation of Brexit and its potential implications changes a bold policy initiative into what may turn out to be an insurance policy for UK innovation.

The research referred to can be found here

Professor Stephen Roper

Director, Enterprise Research Centre

Warwick Business School

Tel: +44 24 7652 2501