Dr Quinton Fivelman, Chief Scientific Officer at London Medical Laboratory, says fighting near Ukraine’s nuclear power facilities brings home the need for a rapid radiation blood test

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine understandably fuelled fears about radiation poisoning, which could have come about either accidentally, because of fighting near Ukraine’s nuclear power plants, or because Russia’s President Putin had deliberately chosen to launch a nuclear weapon.

On 16 March, Yuri Fomichev, Mayor of Slavutych – a city purpose built for evacuated personnel of the Chernobyl power plant in 1986 – warned that Chernobyl could be on the brink of a new nuclear disaster. He claimed that staff there, under the control of Russian soldiers, were physically, morally and psychologically exhausted. He warned: ‘A complete catastrophe’ is looming.

Nuclear contamination does not respect international borders

Following the original Chernobyl disaster, Margaret Thatcher’s government was forced to take action after parts of Cumbria, Scotland and Northern Ireland were impacted, with North Wales the hardest hit. Sheep were still failing radioactive tests 10 years after the accident. The last restrictions on the movement and sale of sheep in the UK were not lifted in 2012.

The Government’s reaction to the arrival of radioactive fallout arriving during a bank Holiday weekend was initially rather shambolic, with Environment Minister William Waldegrave mistakenly quoting the telephone number for the Department of the Environment (DoE) drivers’ pool instead of Whitehall’s technical information centre during a radio interview.

Had the radiation levels been a little more significant, however, farce could have turned to tragedy, with many people falling ill with potential long-term consequences. Nuclear contamination is no respecter of international borders. According to a report by Swedish scientists at Linköping University, radiation from Chernobyl has been cited as a factor in more than 1,000 cancer deaths in Norrland between 1986 and 1999 – this in an area with a population of around one million.

The need for a near instant blood test for radiation poisoning

This is one more reason why ‘Putin’s War’, as it is called in Europe, has highlighted the need for fast tracking research into a near instant blood test to identify radiation poisoning.

Radiation poisoning is traditionally detected by equipment such as Geiger counters. However accurate counters are expensive and not widely available. For this reason, the Government and UK laboratories should join the international effort to speed up the development of a single finger-prick blood test to enable the detection of radiation poisoning.

Ukraine is Europe’s second biggest generator of nuclear power, after France. It has 15 nuclear reactors and four plants. When Russian soldiers reached the decommissioned Chernobyl power plant there was a spike of radiation levels as missiles reportedly hit two radioactive waste disposal sites. It’s a situation that could never have been foreseen by the plant’s designers.

Later in the war Russian troops surrounded Ukraine’s biggest atomic plant, Zaporizhzhia, the second largest plant in Europe. A large-scale incident here could have potentially contaminated wide portions of Europe.

As if this wasn’t enough cause for concern, some military experts also expressed fears that Russia might explode a nuclear weapon somewhere over the North Sea between Britain and Denmark.

Were this unthinkable event to have happened, the option to have a near instant blood test to detect potential radiation poisoning would have proven invaluable.

What is radiation sickness, or acute radiation syndrome (ARS)?

Radiation sickness, or acute radiation syndrome, is a condition caused by a high dose of penetrating radiation in a very short time — usually a matter of minutes. The condition can rapidly weaken a person through its side effects and lead to death without intervention. ARS most often impacts the bone marrow and gastrointestinal systems. Death can occur in a matter of days for the most severe cases, but most patients die within several months of exposure.

That means rapid identification of exposure levels is critical. Currently the only swift ways to detect potential poisoning is by using equipment such as a Geiger counter, which can determine the location of radioactive particles. However, accurate Geiger counters are hardly household items and can be expensive.

Radiation Poisoning can also be detected by blood tests, but it currently requires frequent blood samples over several days to enable medical personnel to look for drops in white blood cells and abnormal changes in the DNA of blood cells. These factors indicate the degree of bone marrow damage.

A single drop of blood could be enough for a rapid radiation blood test

However, a study into a new testing method has the potential to rapidly identify radiation sickness, based on biomarkers measured through a single drop of blood. This could help save lives by providing real-time identification of the condition of a patient to enable timely clinical interventions.

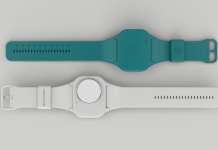

This new test would use just a single drop of blood — collected from a simple finger prick — and results would be ready in a few hours. The test would be rapid, scalable and would enable the screening of many individuals in a short time.

The research has been led by Naduparambil K. Jacob, PhD, an associate professor at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute. Jacob and his colleagues reported their findings in the medical journal Science Translational Medicine in July 2020.

UK Government should prioritise development of this medical tech

However, this research is, as yet, only a proof-of-concept study. Keeping in mind current events, the need for this kind of fast fingerpick blood test for radiation should be given priority.

A variety of treatments are available to help people who have been found to have radiation poisoning. These include treatments for damaged marrowbone and internal contamination. However, some of these can be intrusive and not without risk. A swift test to determine the extent and nature of potential radiation poisoning means doctors can determine on a course of treatment based on accurate information.

The availability of such tests here in the UK would enable the Government and health services to get a near instant analysis of the potential physiological impact of a nuclear incident, whatever the cause. The UK should put its weight behind further research into a swift, accurate radiation blood test.