Clarifying what kind of support is provided by universities in Scotland, as ‘Corporate Parents’, to children and young people who have experienced social care in the UK in comparison with Japan

1. The role of universities as Corporate Parents

Corporate Parenting is defined in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 as ‘a group of people responsible for working together to meet the needs of children in social care (Looked After Children), young people and people with experience of social care’. Corporate Parenting is defined as a ‘formal and local partnership between all services’, often translated and introduced as ‘social co-parenting’ in Japan. It aims to promote the physical, emotional, spiritual, social and educational development of all children from infancy to adulthood, with all organisations in society playing the role of ‘social co-parents’, it is stated (Scottish Government, 2015).

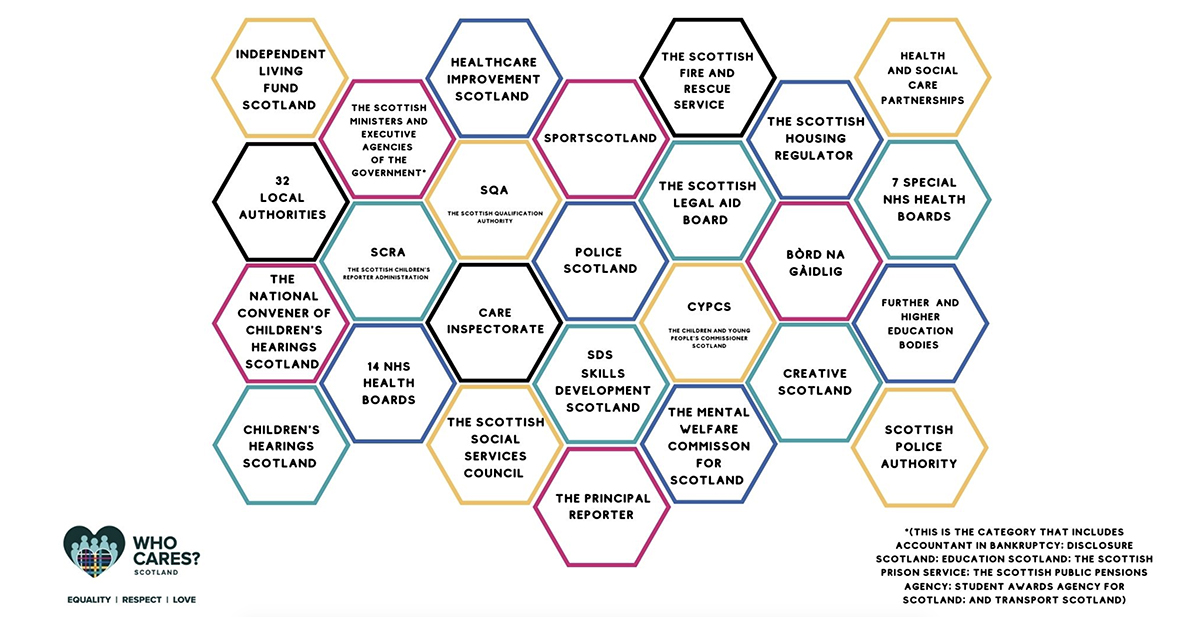

The concept of Corporate Parenting emerged in the late 1990s and has been actively reflected in Scottish Government policy since the 2007 report ‘Looked After Children and Young People: We Can and Must Do Better’. It has been incorporated into the 24 agencies, organisations and occupations currently specified as ‘Corporate Parent’ in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act are listed in figure 1.

2. Support starting before university entry

Many Scottish universities support a diverse range of applicants to university at the pre-entry stage. For example, in addition to children and young people growing up in social care, those attending school through the Scottish School Support Scheme and adults returning to education through the Access Programme (AP) are also eligible for support.

AP is designed for people who have experienced social care, as well as for those who, due to all kinds of circumstances, such as their family financial situation, were unable to go to university immediately after high school graduation and once employed, can go on to university a few years later.

In Scotland, every postcode in the country is ranked from 1 to 100 by disadvantage. Efforts are being developed to increase participation in higher education, mainly for those who are socio-economically disadvantaged and live in postcodes with an index of 1 ~ 40. This is because people living in these postcode areas are statistically less likely to go to university.

The pre-university support programme targets young people from areas that can be identified by postcode, as well as asylum seekers, refugees and students in need of administrative care.

3. Post-university support

Students in the UK apply to universities through the Universities and Colleges Admissions System (UCAS system), which allows students to self-report their social care experience during the application process. This is because self-reporting at this stage can provide support, such as relaxed entry requirements, depending on the university. After being registered as a new student at the respective university, students can then self-report their social care experience at the university again during the nine months in which the new term begins, and the system is designed to connect them with the support they need.

The job of university support staff is to first check that those known to be coming to university with UCAS are registered. They will proactively contact them to let them know what the university can do for them and try to build relationships as early as possible in the early stages of their enrolment so that they can connect the student in question with the support they need. The menu of support available after university enrolment includes additional support for study, disability services and accommodation guarantees. Through this process, the university will develop a comprehensive list of students to be contacted.

Conclusion

So far, I have reviewed, based on data and the results of interviews, what support is provided by universities in Scotland, UK, as ‘Corporate Parents’ to children who are in social care. Based on the above, in the future, in Japan, the guarantee and expansion of educational opportunities for children in social care should not only be practised and discussed at the so-called ‘frontline level’, but also how the legal system should be developed.

For example, the implementation of a programme to support higher education and expand educational opportunities for pre-university children, concerning the WP in Scotland. Instead of suddenly thinking about career paths after high school, children and their carers discuss their dreams and goals for the future together with their foster parents and facility staff from the primary school stage, and collect information on the knowledge and qualifications necessary to realise these dreams and goals, as well as information on places of higher education where these can be acquired and obtained. We would like to examine the possibilities of initiatives to increase the number of universities, colleges and vocational schools across the country that cooperate with such initiatives.

In Scotland, the Greater Glasgow Articulation Partnership (GGAP) funded a ‘trial enrolment’ programme from 2010 to 2006 to support children from socially disadvantaged and economically deprived families to enter schools, such as nursing and art schools. It was implemented as a limited project, but has not been continued since (Mayne, W., et al.: 2015).

In Japan, ‘exchanges between the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises and children’s homes’ are being promoted in Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe and other prefectures (Yamashita: 2019, Asahi Shimbun:2018). I hope to elaborate on future discussions concerning the expansion of efforts to expand support for the future career paths and higher education of children in social care, with such ‘employment image formation’ and ‘expansion of the menu of support for higher education’ as two wheels of the wheel.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.