The Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory studied US cities, uncovering urban heat disparities in air temperature among demographic groups, particularly between black and white residents

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have conducted a comprehensive study on major cities across the United States, focusing on the exposure to air temperature variations experienced by different demographic groups.

Examining urban heat disparities within U.S. cities

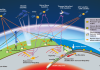

Cities, with their intricate structure varying from densely packed urban centres to expansive suburbs, showcase a complex nature influenced by urban heat disparities.

Within these urban environments, temperature disparities arise, creating heat hotspots that affect different neighbourhoods and residents in varying degrees.

The findings reveal significant disparities between the average temperatures encountered by Black and white residents.

This is also a contribution to racial disparities in the U.S.

On average, Black individuals are exposed to air that is 0.28 degrees Celsius warmer than the city average, while white urban residents experience temperatures that are 0.22 degrees Celsius cooler.

A nationwide estimation of urban heat stress

To develop a more accurate understanding of urban heat stress and its impact on the human body, the researchers undertook a two-part study.

The first objective was to create improved nationwide estimates of heat stress by incorporating various factors that influence how the body responds to outdoor heat.

By comparing these estimates with demographic data, they aimed to identify the populations most affected by urban heat stress.

Uncovering race and income disparities

The study’s results highlight the presence of income- and race-based disparities within U.S. cities.

Approximately 94% of the urban population, equivalent to around 228 million people, resides in cities where the burden of summertime peak heat stress disproportionately affects the poor.

the burden of summertime peak heat stress disproportionately affects the poor

Furthermore, individuals living in historically redlined neighbourhoods, where racial discrimination influenced loan approvals in the past, face higher levels of outdoor heat stress compared to their counterparts in non-redlined areas of the city.

Limitations of satellite-based methods

The research also emphasises the limitations of conventional satellite-based approaches used to estimate urban heat stress disparities.

These methods, which rely on land surface temperature measurements, often overestimate the magnitude of these disparities.

As global temperatures continue to rise, these findings can inform the development of urban heat response plans by local governments, particularly aimed at assisting vulnerable groups.

Physiological effects of heat

The human body operates within a narrow temperature range, and an increase of just six or seven degrees can have severe physiological consequences.

Sweating provides some relief, but its effectiveness depends on the humidity of the environment.

In environments characterised by high heat and humidity, the body struggles to adapt.

Scientists employ various indicators to measure heat stress, many of which rely on air temperature and humidity data obtained from weather stations.

However, since most weather stations are located outside cities, alternative methods are used, such as satellite sensors.

These sensors estimate land surface temperature based on thermal radiation measurements.

However, this approach provides an incomplete representation of heat stress since it only accounts for the surface temperature of the Earth and fails to capture the actual conditions experienced by individuals in an upright position.

To address this, the researchers used a combination of satellite data and model simulations to compare land surface temperature derived from satellites with ambient heat exposure within cities.

They analysed 481 urban areas across the continental United States and generated estimates of variables required to calculate moist heat stress.

By utilising metrics such as the National Weather Service heat index and the Humidex, the researchers captured the combined impacts of air temperature and humidity on the human body.

Poor neighbourhoods and race correlation

The study’s findings indicate that residents in poor neighbourhoods and communities with higher income inequality are more susceptible to heat stress.

Moreover, a strong correlation exists between heat stress disparities and residential segregation based on race.

The research also underscores the need for more comprehensive measurements of urban heat stress, incorporating factors such as wind speed and solar insolation.