A new potential treatment and vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease has been developed by a team of UK and German scientists, using a different approach with amyloid beta protein

According to the NHS, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia in the UK. Dementia is a group of symptoms affecting the gradual decline in brain function, affecting memory and other mental abilities.

In a collaboration between University of Leicester, the University Medical Center Göttingen and the medical research charity LifeArc, a protein-based vaccine and antibody-based treatment created was found to reduce Alzheimer’s symptoms in mouse models of the disease.

Methodology

Published in Molecular Psychiatry, the study focuses on the Amyloid beta protein. This protein exists as highly flexible, string-like molecules in solution, which can join to form fibres and plaques.

A high proportion of these string-like molecules become shortened, and some scientists now think that these forms are fundamental to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

However, rather than analysing amyloid beta protein in plaques in the brain – as they are commonly associated with Alzheimer’s disease – the antibody and vaccine both instead target a different soluble form of the protein, which is thought to be highly toxic.

Professor Thomas Bayer, from the University Medical Center Göttingen, said: “In clinical trials, none of the potential treatments which dissolve amyloid plaques in the brain have shown much success in terms of reducing Alzheimer’s symptoms.

“Some have even shown negative side effects. So, we decided on a different approach. We identified an antibody in mice that would neutralise the truncated forms of soluble amyloid beta but would not bind either to normal forms of the protein or to the plaques.”

Dr Preeti Bakrania and LifeArc adapted this antibody so a human immune system wouldn’t recognise it as foreign and would accept it.

The Leicester research group had a surprise when looking at where this ‘humanised’ antibody, called TAP01_04, was binding to the shortened form of amyloid beta. They found the amyloid beta protein had folded back on itself, in a hairpin-shaped structure, enabling the protein to bind to the antibody.

Professor Mark Carr, from the Leicester Institute of Structural and Chemical Biology at the University of Leicester, explained: “This structure had never been seen before in amyloid beta. However, discovering such a definite structure allowed the team to engineer this region of the protein to stabilise the hairpin shape and bind to the antibody in the same way.

“Our idea was that this engineered form of amyloid beta could potentially be used as a vaccine, to trigger someone’s immune system to make TAP01_04 type antibodies.”

When testing the engineered amyloid beta protein in mice, the team discovered that the mice which received this ‘vaccine’ produced TAP01 type antibodies. Following this, in two different mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, the Göttingen group then tested both the ‘humanised’ antibody and the engineered amyloid beta vaccine, titled ‘TAPAS’.

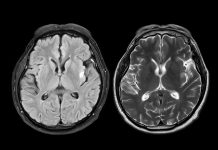

The results found that based on similar imaging techniques to those used to diagnose Alzheimer’s in humans, both the antibody and the vaccine helped to restore neuron function, increase glucose metabolism in the brain, and restore memory loss.

It also successfully reduced amyloid beta plaque formation, limiting the formation of the forms which develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“A promising potential treatment for the disease”

LifeArc’s Dr Bakrania said: “The TAP01_04 humanised antibody and the TAPAS vaccine are very different to previous antibodies or vaccines for Alzheimer’s disease that have been tested in clinical trials, because they target a different form of the protein.

“This makes them really promising as a potential treatment for the disease either as a therapeutic antibody or a vaccine. The results so far are very exciting and testament to the scientific expertise of the team. If the treatment does prove successful, it could transform the lives of many patients.”

Professor Mark Carr added: “While the science is currently still at an early stage, if these results were to be replicated in human clinical trials, then it could be transformative. It opens up the possibility to not only treat Alzheimer’s once symptoms are detected, but also to potentially vaccinate against the disease before symptoms appear.”

Now looking to find a commercial partner, the researchers are to take the therapeutic antibody and the vaccine through clinical trials.