Dr Alison Cernich, Deputy Director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health and Dr Theresa Cruz, Acting Director, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research at NICHD, describe technology that helps children with disabilities

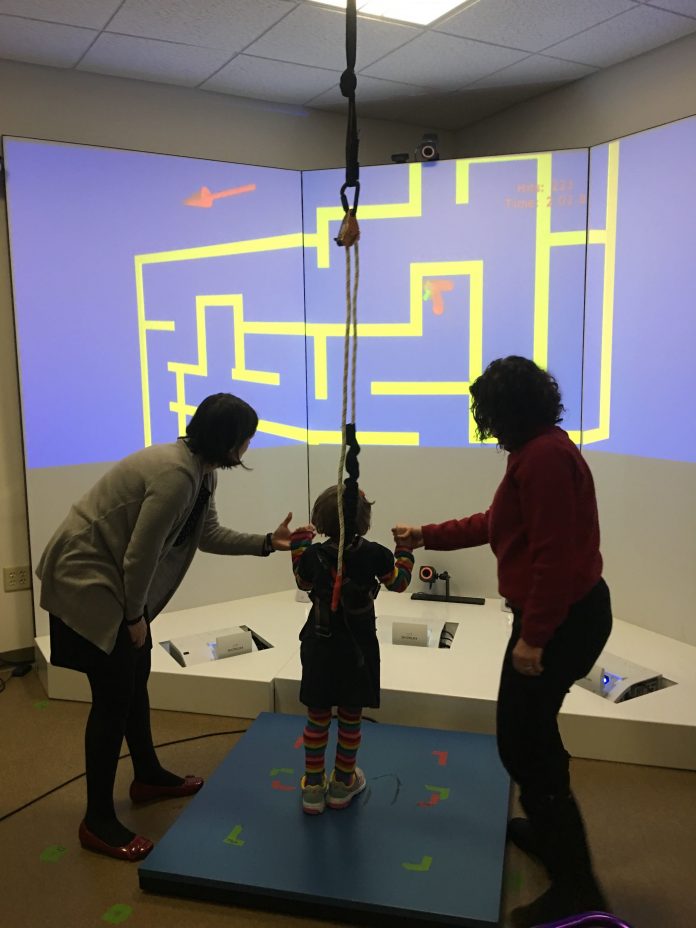

Young Mirabelle, age six, plays in the Rehabilitation Game & Virtual Reality lab of Dr Danielle Levac at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, moving her body to control a ball rolling through a virtual maze.

How virtual environments and gaming affect motor learning processes

Making the precise movements required for the game is deeply challenging for the young girl who has spastic diplegia cerebral palsy, a neurological condition that usually appears in infancy or early childhood and permanently affects muscle control and coordination. The video game helps her strengthen her balance and standing endurance – while having fun – an emerging use of technology aimed at helping children with disabilities. A growing body of research is exploring the benefits of virtual reality games to keep children motivated and engaged in physical therapy and rehabilitation. The games, which can be viewed on twodimensional flat-screen displays or in more immersive three-dimensional, head-mounted displays, captivate children with the goal of promoting retention and the transfer of new movement skills.

Relationships between same task in virtual and physical environments

Dr Levac, a Physical Therapist and Assistant Professor at Northeastern and an NICHD grantee, evaluates how virtual environments and the gaming experience affect motor learning processes and outcomes.

“What is it about the characteristics of practice in virtual environments that might enhance the learning of new movement skills for kids with cerebral palsy?” she asks. Her lab quantifies improvements in performance through game repetition and explores relationships between practice of the same task in virtual and physical environments. One of her primary goals is to determine how well the children transfer the skills they are learning in the virtual environment to real life. Non-invasive measures of brain activity, such as electroencephalography, as well as children’s self-report of motivation and engagement levels, are some of the measures Dr Levac uses to better understand the impact of gaming on motor learning and transfer.

It’s too early to know whether the virtual environments will have a lasting impact, but clearly, technology is becoming ubiquitous and available to physical therapists. As rehabilitation involves repetitive exercises, the rationale for gaming and virtual environment use is clear. Research in the field will help therapists make informed decisions about the best technology for desired outcomes.