Dickon Posnett, Argent Energy’s Director of Corporate Affairs, explains why taking biofuel investors for granted is very bad for climate change, beginning with a discussion about this peculiar market created and nourished entirely by legislation

There are few products we buy simply because we have to. There are few markets that create demand not by desire, but by a law or regulation mandating its use. However, one with this unique peculiarity is the renewable energy market, particularly renewable fuels in transport.

Rudolph Diesel developed his famous engine to run on biofuel well over one hundred years ago but there was no meaningful sale of biofuels anywhere in the world until the biodiesel his engines originally ran on was forced on the fuel supply industry by legal mandates. That was the moment that the investment community pricked up its ears and began building biofuel production plants.

My role at Argent Energy includes overseeing our external, or ‘public’, affairs, which in turn involves monitoring and influencing policy decisions in biofuel markets. It is accomplished by direct contact with policymakers but more often through the important biodiesel industry associations in the UK, other European Union (EU) countries and, of course, the EU. The work with these groups over the last 20 years has afforded a view of the birth of the market through legislation and provided some insights into how the industry behaves over the mid-to-long term in response to it.

The observation discussed here is the decline of policy attention to the use of biodiesel in the decarbonisation of road transport, including heavy-duty vehicles, and the consequent decline in investor interest.

Consequences

In April 2024, we had to announce the news that we plan to close down our biodiesel plant in Scotland. The Scottish plant is no longer viable but had represented the cutting edge of biodiesel production and had been:

- The ‘Demonstration Plant for Europe’.

- The first commercial-scale plant using waste animal fats.

- Employing 75 high-quality people.

- Producing 55,000 tonnes of distilled biodiesel.

- Saving – with its fuel – over 2.5 million tonnes of GHG emissions since March 2005.

The press release pointed to a few of the immediate trading headwinds the industry faces, including huge growth in cheap imports from China. But these are issues we can address with trade defence measures.

But this is only part of the whole story.

And we are not alone. A recent estimate suggested that around 25% of European biodiesel capacity is now idle, at reduced capacity, or closed.

Biodiesel in Europe: What is going on?

After all biodiesel in Europe is highly sustainable. Waste-based biodiesel delivers GHG savings of around 86–91%, while our crop-based colleagues make savings of over 60-70% over fossil fuel. Biodiesel has the lowest carbon abatement costs and is probably the most cost-effective means for decarbonising current Heavy-Duty Vehicles (HDV) and shipping.

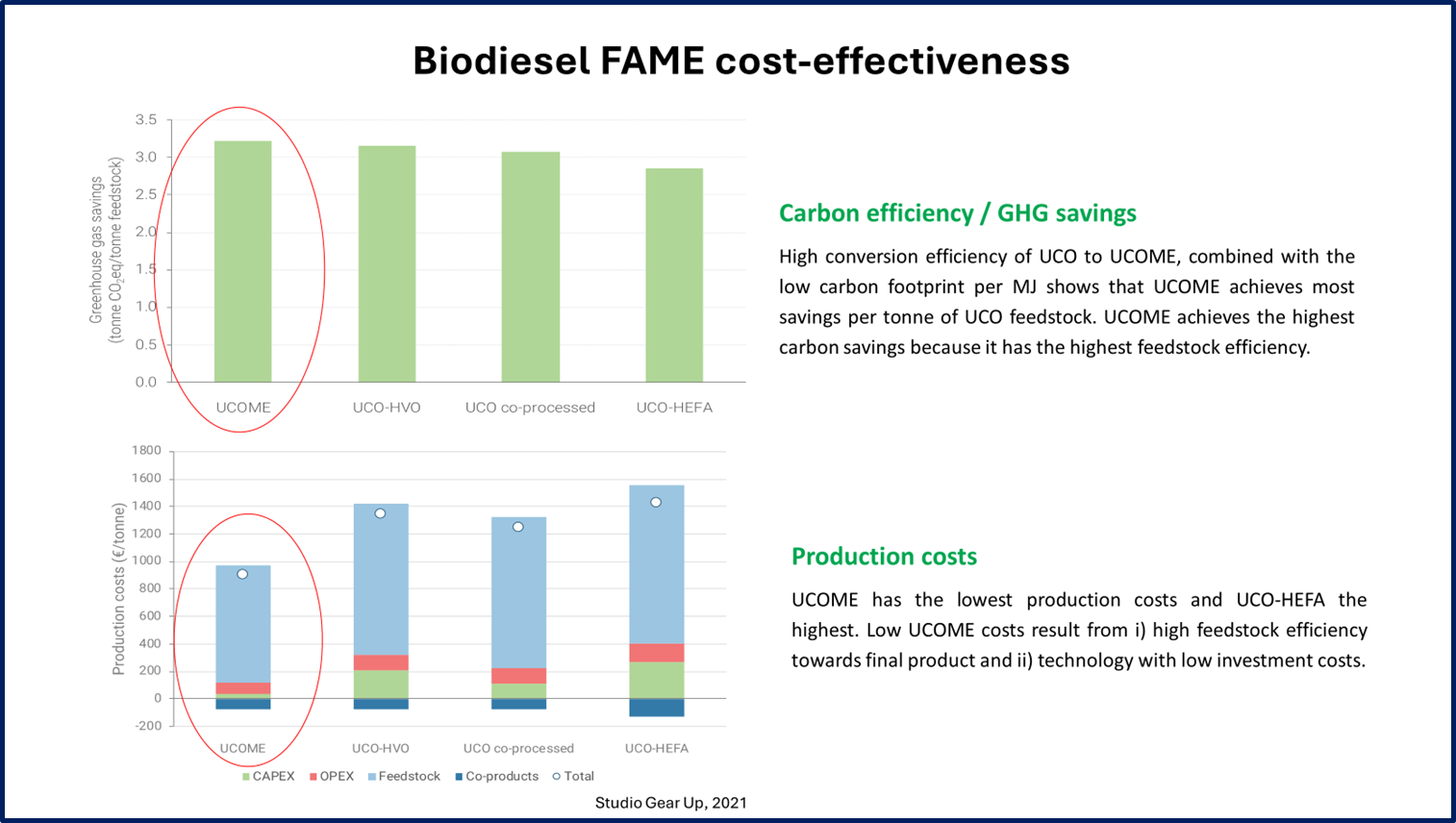

This graph from a Studio Gear Up study compares renewable fuel options, with UCOME representing biodiesel. Of course, all types should be used – we need everything we can get – and it’s evident that biodiesel (FAME) is an important part of the overall renewable fuel mix.

Despite these stark numbers, recent policy measures introduced both in the EU and at the country level clearly show a strong tendency to favour the more recent arrivals on the renewable fuels scene, such as SAF, Sustainable Aviation Fuel, or as a colleague in the airline calls it, Sexy Aviation Fuel.

The other siren call is for electrification. To be clear, the work to decarbonise aviation and, indeed, electrification is an absolute must. So, there are no arguments with the efforts being made.

Sexy, exciting work like SAF and electric vehicles will inevitably grab the headlines and make great soundbites. However, biodiesel must not be forgotten in terms of policy support.

The only reason FAME production exists in Europe and globally is that there has been a demand large enough to convince investors to build facilities. That demand has come solely from the levels dictated in legislative mandates.

Change of emphasis in legislation for renewable fuels

There are now more and more policy moves to restrict, curtail, reduce, and prioritise against biodiesel that should be going to HDVs. Some examples we see today:

- The cap on the use of sustainable crop-based biodiesel in Europe.

- An exclusion of crop-based biodiesel from use in aviation and shipping sectors in Europe (e.g. ‘RefuelEU Aviation’ and ‘ReFuelEU Maritime’.)

- A cap on waste-based biodiesel from animal fats (that has no other use) and used cooking oil.

- The UK’s mandate for SAF forces a diversion of the biodiesel sector’s feedstocks into aviation and away from biodiesel.

- Those decisions recently have clearly been against investing in biodiesel, despite its amazing history and leading decarbonisation credentials.

Even the G7 noted the need to support sustainable biofuels.

The biofuels market: Use it or lose it

It is a unique peculiarity of renewables, and in particular renewables in transport, that due

to the way the fuel supply market is structured in Europe and around the globe, the market for biofuels is almost entirely created by the imposition of mandates.

Investors watch this landscape closely for signals that could affect investment decisions. Possibly unconsciously, in the last three or four years, those signals have changed from green to amber for biodiesel manufacturing, and the decline in use and availability of the cheapest form of decarbonisation of HDVs is the signal back from an industry that it cannot afford to be taken for granted.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.