Antibodies have been discovered in the populations of northern gannets and shags in Scotland, with a significant decrease in poultry infections across the United Kingdom

Scientists have observed that certain avian species have gained immunity to avian flu, raising hope that the lethal virus may claim fewer bird lives in the upcoming winter. The ongoing H5N1 bird flu epidemic, which started in 2021, is the most severe on record and is believed to have resulted in the deaths of countless wild birds. Although the mortality rates appeared alarmingly high among wild birds, it remained unclear how many managed to survive and develop immunity.

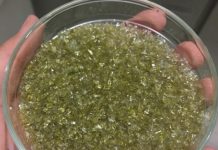

The H5N1 virus

Initial investigations conducted by a collaborative team of scientists have confirmed the presence of immunity in two seabird populations. The researchers collected blood samples from northern gannets located on Scotland’s Bass Rock, a location severely impacted by avian flu in 2022, and discovered that 30% of them had developed antibodies.

Ornithologists hold special concern for this species in Britain, which hosts approximately two-thirds of the global northern gannet population. Bass Rock is the world’s largest colony of these birds. The scientists also examined shags and ascertained that roughly half exhibited immunity.

Conducted by the FluMap consortium spearheaded by the APHA, the pivotal findings from their study have been officially published in Ibis, the renowned International Journal of Avian Science.

Recent changes in the UK

The sample size was limited, consisting of roughly 30 birds from each population. Brown noted that capturing and obtaining blood samples from wild birds was exceptionally difficult, partly explaining why this endeavour was unprecedented. Nevertheless, the results corroborate the observations made by conservationists, indicating that certain birds have indeed developed immunity. A notable example is the gannets, whose usual blue irises changed to black after surviving infection.

Due to the virus’s rapid mutations, the duration of immunity and the initial survival rate of birds against avian flu remains uncertain. Seabird populations recover slowly because they typically produce only one or two offspring yearly, raising concerns about long-term impacts.

Researchers aim to expand their investigations to other wild birds, especially those living on farms, to determine how the virus enters poultry sheds. They’ve noted that the virus typically travels short distances, less than 10 meters, suggesting it’s primarily transmitted by wild birds rather than through the air between farms.

Monitoring the Evolution of H5N1

Researchers are closely monitoring the situation this winter, particularly in October when migratory birds arrive, potentially introducing new virus variants.

From October 1 to October 28, 2022, there were 58 confirmed poultry cases in Britain. This year, as of October, there have been no reported cases. On a global scale, there are only a few poultry cases in northern Europe and a small number in wild birds.

The H5N1 virus possesses several genes that can mutate and adapt collectively, enabling the rapid transmission of the virus across various species. The most recent outbreak originated from alterations in the virus, which significantly increased its lethality and transmissibility. Recent developments in the prevailing H5N1 strain in the UK indicate a potential shift towards reduced virulence.